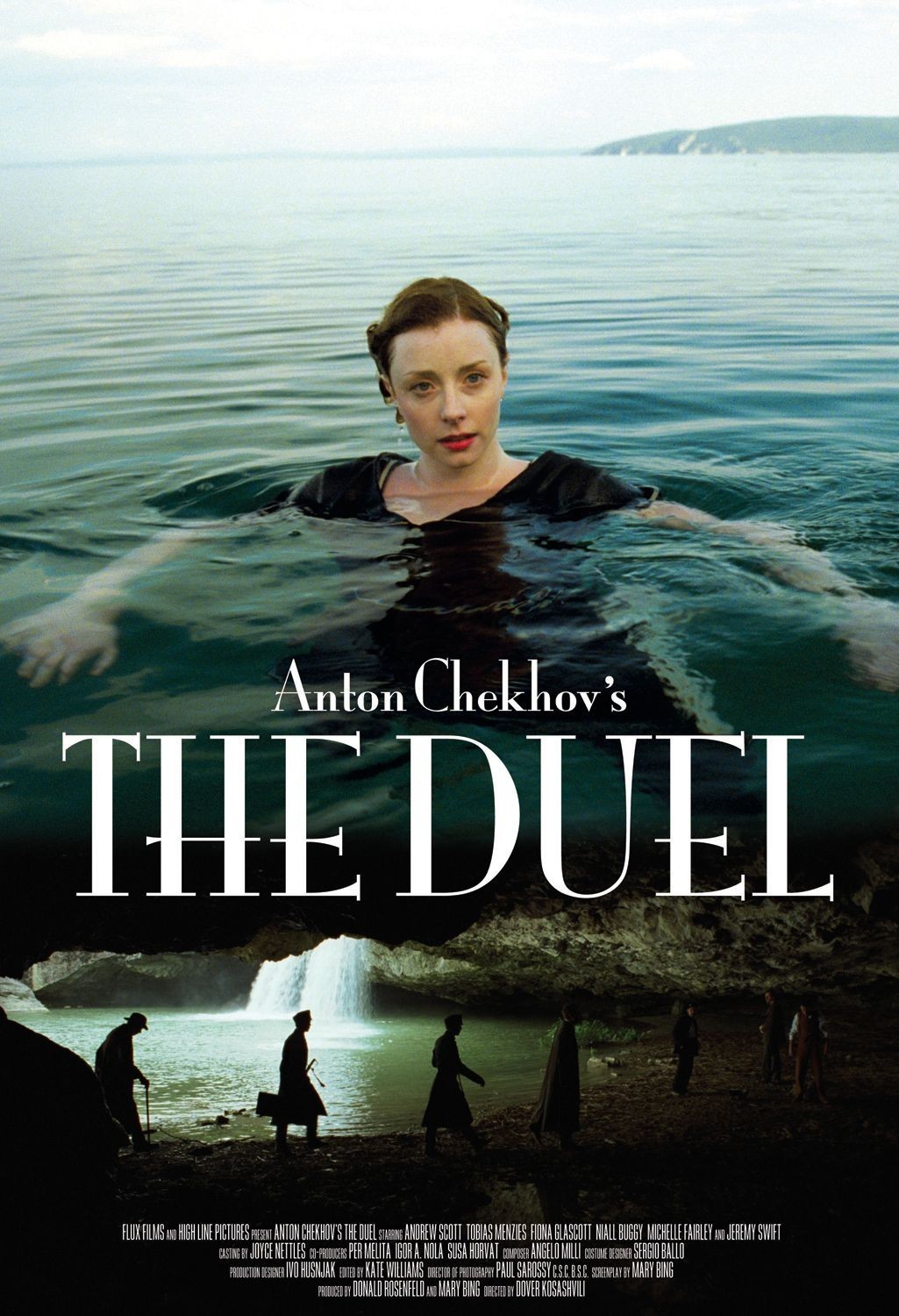

What strikes you immediately about “Anton Chekhov’s The Duel” are the visuals. The cinematography of Paul Sarossy composes shots as an impressionist romance, the colors tastefully softened, the elements arranged in classical symmetry. Unfortunately, this combined with the unwavering progress of the story results in much of a muchness, and we wouldn’t object to the occasional taste of vulgarity.

Laevsky (Andrew Scott) is one of those civil servants of 19th century Russian literature who seems high up on an insignificant ladder. He’s shacked up in this seaside resort with his married mistress, Nadia (Fiona Glascott), who has lost her appeal now that she’s freed of her husband. I’ve been reading a lot of Balzac lately and am struck that absent husbands in European classics seem to play much like “Noises Off.” Laevsky expresses his discontents to the local physician, Dr. Samoylenko; Chekhov often provides such learned listeners to sit gravely through anguished monologues. Samoylenko is required not for his diagnosis but for his ears. Also for his money: Laevsky is a gambler and drunk who desperately hopes for a loan.

Into this powder keg comes the zoologist Von Koren (Tobias Menzies), inflamed with the revolutionary principles of Darwinism, which were then being embraced by the intelligentsia in all the wrong ways. Rare is the man not convinced that all evolution points like an arrow to his door. Von Koren is too refined to enter a horse of his own in the race, but he observes with scientific precision the willingness of the locals to respond to Nadia’s underemployed sexuality. All comes to a head at a party one night when the overserved Laevsky temporarily goes barking mad, and Von Koren determines he isn’t fit to survive.

The zoologist then faces one of the two choices open to him, given his rudimentary grasp of Darwin’s theory. If he wants little Von Korens to prevail over little Laevskys, he can either seduce the female or kill the man. “Anton Chekhov’s The Duel” is by no means shy about portraying sex in a forthright manner, and director Dover Koshashvili has gratifying taste in nudity, which has grown sadly rare as Friday night audiences lose their interest in it. But Von Koren is too much of a lard-ass to seduce Nadia and he knows it, so he challenges Laevsky to a duel instead.

One of two men will die over this woman: Man No. 1, who no longer desires her, or Man No. 2, who knows what he would do if only he were in Man No. 1’s shoes. For Nadia, this must not be quite as exciting as Rhett Butler calling out Ashley Wilkes. The doctor saw it all coming, but then doctors are always seeing it all coming.

Koshashvili is a good filmmaker. His “Late Marriage” (2001) involved some of the more practical difficulties of an arranged marriage in Israel among immigrants from Soviet Georgia. Its characters had the advantage of caring strongly about who they did or didn’t sleep with. In “The Duel” and much of Chekhov, lust seems to be a matter best approached by the introspection of the world-weary.

“Anton Chekhov’s The Duel” isn’t exactly a bad film. It’s very well made and acted in English by a mostly Irish cast in a polished Chekovian tone. But it somehow isn’t as exciting as a duel over a woman should be. If you’re not well rested before entering the theater, it could put you under.