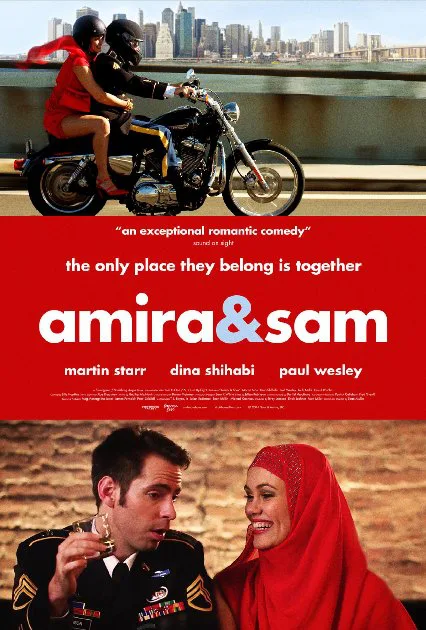

“Amira & Sam” tells the “unlikely” story of the romance between a United States Army Special Forces vet who served in Iraq and an undocumented immigrant from that country. What’s important here is that writer/director Sean Mullin (his feature debut) keeps quotation marks around the perceived “unlikeliness” of their romance. There is ultimately nothing strange or conflicted about their connection. It develops at its own, natural pace. It’s simply the story of two people who learn about each other’s life and interests, and out of that, mutual affection grows.

There are kinks in its progression, of course. Sam (Martin Starr) and Amira (Dina Shihabi) have a rough start upon their first meeting. He’s visiting Amira’s uncle Bassam (Laith Nakli), who served as a translator for Sam’s unit in Iraq and whom Sam saved during an ambush. Amira’s brother was killed in the crossfire during a different attack, and she sees Sam as just another American soldier who, in her mind, is as responsible for her brother’s death as the soldiers who were there that day.

It’s a pretty big hurdle, but Mullin sees personal connections as indeterminable feelings that go beyond politics and history. Bassam explains how Sam saved his life, upheld a promise to see him again, and presented him with the star from a burnt American flag he tried to save during the firefight. Whatever prejudices Amira previously had slowly dissipate—at least for this man—as she starts to learn that he’s not representative of American foreign policy or the soldiers who couldn’t protect her brother. He’s just a decent guy.

With her internal obstacles to overcome, Amira is the more intriguing part of the pair, although Mullin’s screenplay is far more interested in Sam. His problems are entirely external and more than a bit contrived.

They begin honestly enough. Sam is fired from a security job at an apartment building after locking a group of disrespectful, drunk residents in an elevator. His cousin Charlie (Paul Wesley), a hedge fund manager who helped him get the job, offers Sam a chance to woo a prospective investor—a Vietnam vet named Jack (David Rasche)—with the promise of a hefty commission if the multimillion-dollar deal goes well. The movie is set during the summer of 2008, mere months before the financial crisis. As one would expect with such a loaded setting, there is an obvious aura of corruption in this subplot.

All of the things Mullin avoids in the romance between Sam and Amira are present in these scenes—the heavy-handed political statements (Jack decries the “cesspool of self-interest” that is the American economic system), the transparent use of characters to represent concepts instead of existing as actual people (Charlie says he’s merely a “prisoner” of free-market capitalism), and an overall sense that Mullin wants to say something Important. The romance itself seems rife with opportunities to do something similar. After all, Sam and Amira are forced into close quarters after she is arrested for selling bootleg DVDs and flees a police officer, which leads to her going into hiding to avoid deportation. Whatever Mullin could or may want to say about the politics of this issue is left off the table. It’s merely a plot point. If we want to connect the movie and a critique of immigration policy, that is entirely on us.

Their story is better for the absence of sweeping political declarations. It’s uncomfortable but tender in the way of any burgeoning romance. The two characters talk as if there isn’t a cloud of impending doom hanging over them. It culminates in a scene in which the two—both of them stubbornly wanting to sleep on the floor—share the bed in Sam’s studio apartment. It’s pillow talk but without the sex. They laugh, share some secret information about their lives (Sam wants to become a stand-up comedian, and Amira says or jokes that she likes to punch people who deserve it), and test out the waters of getting physical with each other (which turns into each playfully licking the other’s cheek).

Almost the entirety of their relationship feels as unencumbered with petty, artificial conflict as the characters are in that scene. Mullin’s only obvious attempt to address the social and ethnic distinctions between these characters comes during a late scene at Charlie’s engagement party, where the characters encounter an onslaught of casual and blatant bigotry. A random woman asks Amira, referring to her hijab, “Do they make you wear that thing?” One of Charlie’s co-workers (Ross Marquand) thinks she looks like Aladdin’s girlfriend. Sam’s uncle (Mark Elliot Wilson) goes on a rant linking all Arabs to the attacks on Sept. 11, 2001. Of course, this aspect of their relationship, sadly, needs to be addressed, but it comes so late and with such bluntness that it feels forced.

There’s just enough of that feeling throughout the movie to undermine the more natural elements of the love story. That’s especially true of the subplot of Sam’s professional involvement with Charlie, which takes up so much of the movie that Amira and what she’s facing seem like an afterthought. When the eponymous couple is together, “Amira & Sam” is an earnest and considerate examination of two people falling in love, but the movie lacks certainty when handling these characters separately.