‘We’ll catch the early staff boat and get there before the tourists arrive,” A.M. Kathrada told my wife and me in Cape Town in November 2001. We were going the next morning to visit Robben Island, where for 27 years Nelson Mandela and others accused of treason, including Kathrada, were held by the South African apartheid government. We were having dinner with Kathrada, who is of Indian descent, and his friend Barbara Hogan, who won a place in history as the first South African white woman convicted as a traitor.

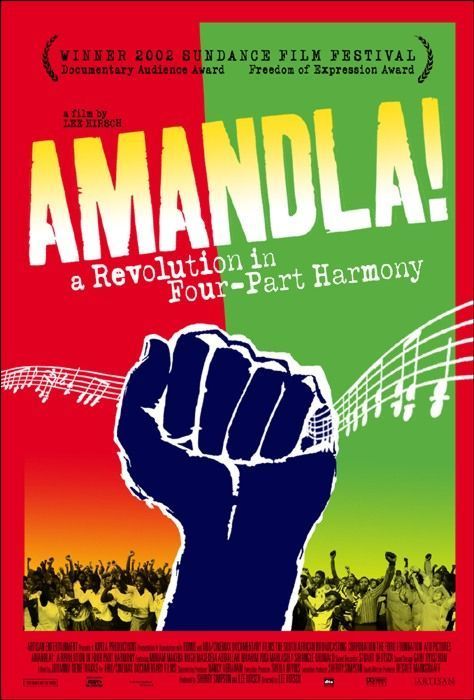

In those days it was easy to become a traitor. “Amandla!,” a new documentary about the role of music in the overthrow of apartheid, begins with the exhumation of the bones of Vuyisile Mini, who wrote a song named “Beware Verwoerd!” (“The Black Man Is Coming!”), aimed at the chief architect of South Africa’s racist politics of separation. Mini was executed in 1964 and buried in a pauper’s grave.

Robben Island lies some 20 miles offshore from Cape Town, and the view back toward the slopes of Table Mountain is breathtaking. When I was a student at the University of Cape Town in 1965, friends pointed it out, a speck across the sea, and whispered that Mandela was imprisoned there. It would be almost 25 years until he was released and asked by F.W. de Klerk, Verwoerd’s last white successor, to run for president. No one in 1965 or for many years later believed there would be regime change in South Africa without a bloody civil war, but there was, and Cranford’s, my favorite used bookshop, can now legally be owned by black South Africans; it still has a coffeepot and crooked stairs to the crowded upstairs room.

Kathrada, now in his early 70s, is known by everyone on the staff boat. At the Robben Island Store, where we buy our tickets, he introduces us to the manager–a white man who used to be one of his guards and smuggled forbidden letters (“and even the occasional visitor”) on and off the island. On the island, we walk under a crude arch that welcomes us in Afrikaans and English, and enter the prison building, which is squat and unlovely, thick with glossy lime paint. The office is not yet open and Kathrada cannot find a key.

“First I am locked in, now I am locked out,” he observes cheerfully. Eventually the key is discovered and we arrive at the object of our visit, the cell where Mandela lived. It is about long enough to lie down in. “For the first seven years,” Kathrada said, “we didn’t have cots. You got used to sleeping on the floor.” White political prisoners like Barbara Hogan were kept in a Pretoria prison. There were not a lot of Indian prisoners, and Kathrada was jailed with Mandela’s African group.

“They issued us different uniforms,” he observed dryly. “I was an Indian and was issued with long pants. Mandela and the other Africans were given short pants. They called them ‘boys’ and gave them boys’ pants.” A crude nutritional chart hung on the wall, indicating that Indians were given a few hundred calories more to eat every day because South African scientists had somehow determined their minimal caloric requirements was a little greater than those of blacks.

Weekdays, all of the men worked in a quarry, hammering rocks into gravel. No work was permitted on Sunday in the devoutly religious Afrikaans society. The prisoners were fed mostly whole grains, a few vegetables, a little fruit, very little animal protein. “As a result of this diet and exercise, plus all of the sunlight in the quarry,” Kathrada smiled, “we were in good health and most of us still are. The sun on the white rocks and the quarry dust were bad for our eyes, however.” During the 1970s, the apartheid government clamped such a tight lid on opposition that it seemed able to hold on forever. The uplifting film “Amandla!” argues that South Africa’s music of protest played a crucial role in its eventual overthrow. Mandela’s African National Congress was nonviolent from its birth until the final years of apartheid, when after an internal struggle one branch began to commit acts of bombing and sabotage (murder and torture had always been weapons of the whites). Music was the ANC’s most dangerous weapon, and we see footage of streets lined with tens of thousands of marchers, singing and dancing, expressing an unquenchable spirit.

“We lost the country in the first place, to an extent, because before we fight, we sing,” Hugh Masekela, the great South African jazzman, tells the filmmakers. “The Zulus would sing before they went into battle, so the British and Boers knew where they were and when they were coming.” There was a song about Nelson Mandela that was sung at every rally, even though mention of his name was banned, and toward the end of the film there is a rally to welcome him after his release from prison, and he sings along. It is one of those moments where words cannot do justice to the joy.

“Amandla!” (the Xhosa word means “power”) was nine years in the making, directed by Lee Hirsch, produced with Sherry Simpson. It combines archival footage, news footage, reports from political exiles like Masekela and his former wife Miriam Makeba, visits with famous local singers, an appearance by Archbishop Desmond Tutu and a lot of music. The soundtrack CD could become popular like “Buena Vista Social Club.” After the relatives of Vuyisile Mini disinter his bones, he is reburied in blessed ground under a proper memorial, and then his family holds a party. Among the songs they sing is “Beware Verwoerd!” It is not a nostalgia piece, not a dusty, not yet. They sing it not so much in celebration as in triumph and relief.