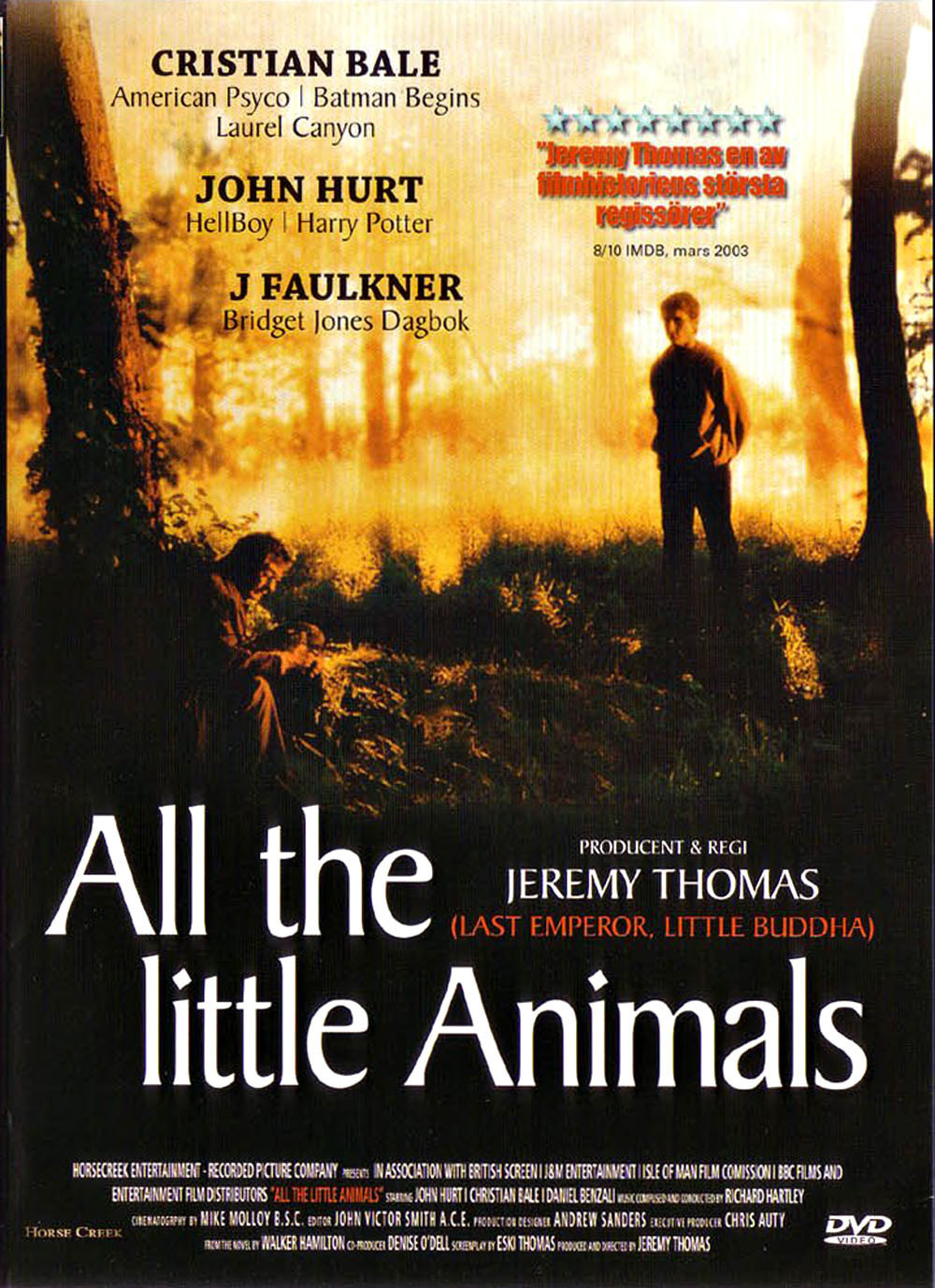

“All the Little Animals” is a particularly odd film that, despite its title, is not a children’s movie, a cute animal movie or the story of a veterinarian, but a dark and insinuating fable. Because it falls so far outside our ordinary story expectations it may frustrate some viewers, but it has a fearsome single-mindedness that suggests deep Jungian origins. Like the 1989 fantasy “Paperhouse,” it seems to be about more than we can see.

Its hero is a 24-year-old named Bobby (Christian Bale), who sustained some brain damage in a childhood accident and is now slightly impaired and often fearful. Much of his fear is justified; his stepfather De Winter (Daniel Benzali) killed Bobby’s mother by “shouting her to death,” and now threatens him with imprisonment in a mental home unless he signs over control of the family’s London department store.

Bobby flees. He hitches a ride with a truck driver who gleefully aims to kill a fox on the road. Bobby wrestles for the wheel, the truck overturns, the driver is killed, and everything is witnessed by a man standing beside the road. This is Mr. Summers (John Hurt), a gentle and intelligent recluse who lives in a cottage in the woods and devotes his life to burying dead animals. “The car is a killing machine, pure and simple,” Mr. Summers snaps; he is even offended by the insects that die on windshields.

Who is this man, really? What’s his story? Why does he seem to have plenty of money? The movie is all the more intriguing because it roots Mr. Summers in reality, instead of making him into some kind of fairy tale creature. He heats Campbell’s soup for Bobby, gives him a blanket, tells him he can stay the night. There is no suggestion of sexual motivation; Mr. Summers is matter of fact, reasonable and motivated entirely by his feelings about dead animals.

Bobby follows the man on his rounds, and then asks to stay and share his work. Mr. Summers agrees. Sometimes they go on raids. One is a guerrilla attack on a lepidopterist, who has built a trap for moths in his backyard, and sips wine and listens to classical music while the helpless creatures flutter toward nets around a bright light. “Smash his light!” Mr. Summers spits, and Bobby runs awkwardly forward with a rock to startle the smug bug collector.

All goes well until De Winter comes back into the picture, and then Bobby and Mr. Summers tell each other their stories, and we learn that the movie is not a simple tale of good and evil, and that Mr. Summers is a great deal more complicated than we might have anticipated. When he’s heard Bobby’s story, he suggests they visit De Winter and simply sign over the store to gain Bobby’s freedom–but De Winter doesn’t see it that way, especially not after Summers (who looks a little shabby) sneezes and gets snot on De Winter’s exquisite suit.

The performances are minutely observed, which enhances the movie’s dreamlike quality. Hurt builds Mr. Summers out of realistic detail, and Benzali makes De Winter into a cold, hard-edged control freak; he’s a villain that would distinguish any thriller and redeem not a few. What drives him? Why is he so hateful? Perhaps he’s simply pure evil, and entertains himself by putting on a daily performance of malevolence. Of course anyone so rigidly controlled is trembling with fear on the inside.

Here’s an intriguing question: What is this movie about? It’s not really about loving animals, and indeed it’s creepy that Mr. Summers (and Bobby) focus more on dead ones than living specimens. Is it about death? About fear, and overcoming it? About revenge? The appeal of archetypal stories is that they seem like reflections of the real subject matter: Buried issues are being played out here at one remove.

Most movies are one-dimensional and gladly declare themselves. This movie, treated that way, would be about an insecure kid, a vicious stepfather and a strange coot who lives in the woods. But “All the Little Animals” refuses to reduce its story to simple terms, and the visible story seems like a manifestation of dark and secret undercurrents. Even the ending, which some will no doubt consider routine revenge, has a certain subterranean irony. The film is by a first-time director, Jeremy Thomas, a leading British producer who has worked with such directors as Bernardo Bertolucci, Nicolas Roeg and David Cronenberg. He says he was so struck (indeed, obsessed) by the original novel by Walker Hamilton that he felt compelled to film it. He has wisely not simplified his obsession or made it more accessible, but has allowed the film to linger in the shadow world of unconscious fears.