The adage that holds “the personal is the political” has been batted around for decades, and it’s certainly one worth considering in the wake of, say, the U.S. Supreme Court’s recent overturning of Roe v. Wade. It’s certainly not a universally accepted sentiment; the late critic Terry Teachout objected strongly to it: “It all goes back to that phrase I hated the first time I heard it—the personal is the political. No, the personal is the personal,” he wrote back in 2004. He was a conservative, after all.

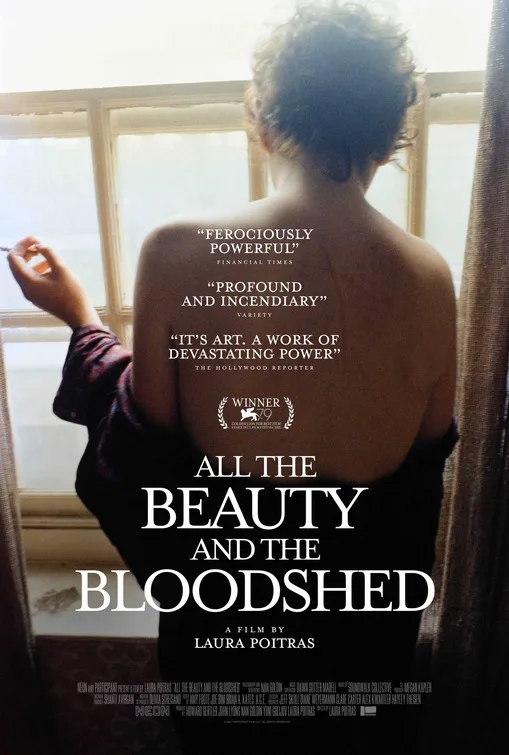

The documentarian Laura Poitras (“Citizenfour,” “Risk”), in collaboration with her subject Nan Goldin, covers a lot of ground about, among other things, the way money affects both the personal and the political, whether you opt to segregate them or not, in this surprising and moving documentary. “All the Beauty and the Bloodshed” chronicles Goldin’s life in art, serving up substantial and vivid portions of her photography, which she exhibited in 1985 as the slideshow with music called The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, which made her name. Since then her work has been displayed in prominent and prestigious museums. She did protean work as an AIDS activist in the past, and a close call with a pain medication overdose—not to mention the deaths and addiction spirals of several friends—compelled her to look into a discomfiting fact.

That is, many of the prominent and prestigious museums that displayed Goldin’s work had accepted substantial contributions from the Sackler family. The same Sackler family that got its money by collaborating with Big Pharma (the corporate connections are such that the term has to serve as shorthand here) on creating a worldwide opiate addiction crisis. By, among other things, severely understating the addictive qualities of its wonder drug OxyContin.

So while Goldin never hung up her activism badge (her work, intimate and autobiographical as it is, is in many respects a forceful statement on the societal marginalization of women and LGBTQ persons), she finds herself, with some initial sheepishness, pinning it back on and staging protest events at institutions that have in some way supported her living.

As it happened, she chose an opportune time to do so. Her mini-movement coincided with a lot of journalistic curiosity about the Sacklers’ money. Patrick Radden Keefe, who was working on an investigative piece about the Sacklers for the New Yorker, recalls here sheepishly that in his initial contact with Goldin, he was slightly dismissive of her, wishing her luck with her project. But their combined efforts created an amplification. Subsequent civil court cases have required the Sacklers to pay monumental fines (which, it is noted with no small irony near the end, has little to no impact on the remaining personal fortunes of family members) and yes, museums are taking the family’s name off of certain rooms heretofore dedicated to/by them.

But “All the Beauty and the Bloodshed” is hardly a simplistic cheerleading account. It’s a story of the political and of the social/sociological, about Goldin’s overall life story. How she grew up in the repressive 1950s, and the toll that environment took on her beloved older sister, who upon discovering her sexuality had no understanding person to turn to. The chronicle of her fate shows a determinant force in Goldin’s life and the life of this country. It won’t do to describe it in more detail because the movie has a maximum impact as an unspoiled narrative. The compassion expressed here, and the rich complexity of everything the movie takes in, make this Poitras’ best film.

Now playing in theaters.