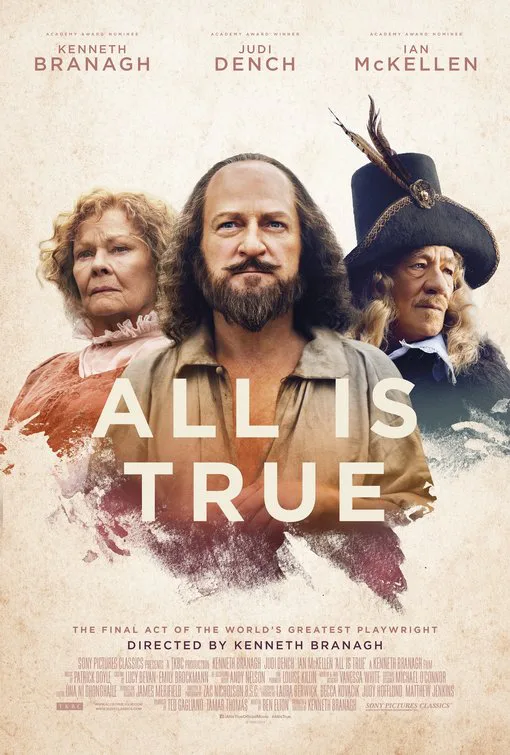

As an actor and director, Kenneth Branagh has presented several works of Shakespeare for cinematic consumption, bringing flair, passion, humor and a bit of randy action to plays like Much Ado About Nothing and Henry V. And like his Bard-loving predecessor, Sir Laurence Olivier, Branagh has run the gamut from Hamlet to ham. Unless you count his take on Frankenstein, Branagh has yet to fully commit to the lovely depths of trashiness that Sir Larry O. plundered. While I eagerly wait for him to breathe life into some dismal Harold Robbins smut, I must settle for his crafty bit of meta-casting in “All Is True.” After taking on several of his plays, Branagh now takes on Shakespeare himself.

Aided by more than a little makeup and a history bending script by one-half of the duo who created the immortal “Blackadder,” Branagh’s Bard is an unexpectedly subdued performance. Shakespeare suffers the kinds of neuroses that plague every writer, except he’s taken up gardening rather than booze to ease his pain. Branagh doesn’t chew the scenery; he mows it in widescreen compositions that are quite often lush and comforting. Shakespeare will never win any awards for his lawn nor will his garden blossom like his prose, but this drudgery gives him something to do.

Writer Ben Elton spins this film’s speculative yarn during the last years of Shakespeare’s life, of which the opening titles tell us not much is known. We do know, however, that in June of 1613, the Globe Theater burned to the ground in London. As “All Is True” opens, Branagh juxtaposes his character against a screen filled with raging fire, visually casting him into the scorching Hell that is writer’s block. Without the theater where his greatest works premiered, Shakespeare has lost his way with words. Vowing to never write again, he returns to Stratford-upon-Avon where his wife Anne Hathaway (Judi Dench) has been holding down the fort in his absence.

Anne seems rather exasperated to see him—she’s gotten on quite well with an absentee husband—but she welcomes him back home. Shakespeare is also reunited with his daughters Susannah (Lydia Wilson) who is married and Judith (Kathryn Wilder), who is not. Anne offers her husband her bed, because “a guest deserves the host’s best bed.” Anne will not occupy it with him; instead she’ll take the “second best bed” in the house. Later in the film, when he’s updating his will, Shakespeare leaves Anne that second best bed as an in-joke between the two of them.

I know what you’re thinking: This is going to be one of those biopics where all sorts of ridiculous coincidences will beget well-known details about that person’s life or their art. “All Is True” bypasses that cliché trap with its timeframe. Besides, the film has other “Walk Hard: The Dewey Cox Story”-worthy sins to commit, starting with the tragic figure who haunts the main character. Shakespeare is tormented by the death of his son Hamnet, whom he thought would pick up his writer’s mantle and continue his legacy. We see Hamnet several times offering his dad the latest poems he has written. Meanwhile, Shakespeare’s relationship with Hamnet’s twin, Judith is strained because, you guessed it, the wrong kid died. Judith even says this line in the movie, leading me to curse Dewey Cox for what he hath wrought.

Branagh doesn’t let you get too focused on predictable things like this—he’s running some equally distracting counter-programming at the same time. Judith’s constant snark evokes MTV’s Daria and her rivalry with her sister has more than a bit of “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof” about it. Unless Judith can offer a male heir for her father to leave his inheritance, she’ll basically be out-of-luck. Meanwhile, Lydia is married to the dull type of Puritan who’s more adept at burning theaters than fanning the flames of sexual passion. Still, they have kids and Judith does not, which puts her at a disadvantage.

“All is True” also wants to delve into the societal roles for women in Elizabethan times. We spend just as much time with Shakespeare’s women as we do with him. While Lydia gets her freak on outside her marriage, Judith seethes at her father as he mopes about lamenting his dead son. Wilder really makes you feel the hurt underneath her moments of lashing out, so much so that Shakespeare becomes a somewhat villainous representation of how little his era valued women.

Anne seems to be the only one comfortable with her life and her delusions. When the truth comes out about Hamnet’s death and his poetry, Anne digs in her heels about the lie she agreed upon telling. Branagh’s framing of this scene, wherein he is dwarfed in the background between Anne and Lydia, is as powerful as Dench’s acting. Say what you want about his onscreen vices, but Branagh has always been a charitable director and it really shows here.

But make no mistake, this is still the same guy who went full-on operatic in the massively entertaining “Dead Again.” Just when it feels like the Bard really doth protest too much about his misery, the film gets a major injection of juicy theatrics courtesy of Sir Ian McKellen. Like Branagh, McKellen is no stranger to the Bard nor is he unfamiliar with dousing his performance with figurative pork products. Sir Ian plays the Earl of Southampton, who has come to visit Shakespeare while in town on other business. This is the guy to whom the Bard supposedly wrote those sonnets. McKellen is delectably foppish, showing up like Edward Everett Horton disguised as an old theater queen. With his thick mustache and outrageous Scarlet Pimpernel wig, he throws enough shade to cover three rooms of windows.

Shakespeare really lusts for the Earl, but the Earl basically says “you’re not regal enough for these goodies.” In a botched attempt at seduction, Shakespeare recites Sonnet 29 in its entirety. You know the one: “When in disgrace, with fortune and men’s eyes” and so on. Branagh digs into the recitation, reminding us of his prowess in matters of the Bard. After the Earl rejects Shakespeare’s advances, he also recites the sonnet to show the Bard that his feelings might have been requited if he were royalty. Not to be outdone, McKellen gives the sonnet a completely different, though no less spectacular reading. As far as acting battle royales go, this is one for the books.

“I never let the truth get in the way of a good story,” Shakespeare tells us. Purists may have a field day with “All Is True,” and it does have a tendency to lag, but I found myself thinking about it days after I’d seen it. Like the superior Emily Dickinson vehicle “Wild Nights With Emily,” it bypasses the worthy immortal regard earned by the writer’s works and lets us see the humanity—and the drama—beneath that surface.