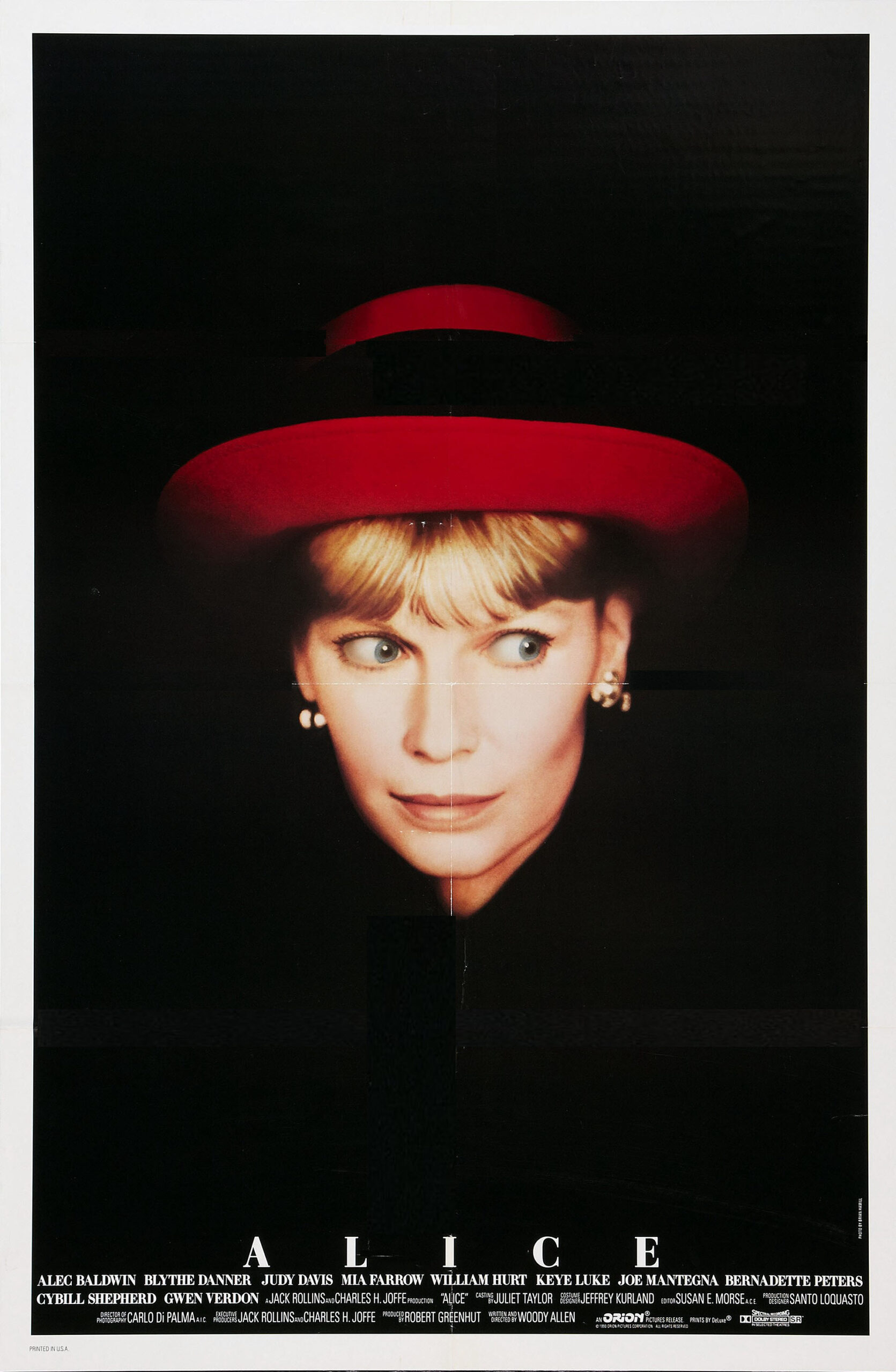

Woody Allen‘s “Alice” snatches its heroine out of the cradle of luxury and takes her on a dizzying tour of the truths in her life, fueled by the mysterious herbal teas of an enigmatic acupuncturist.

It’s a strange, magical film, in which Allen uses the arts of the ancient Chinese healer as a shortcut to psychoanalysis; at the end of the film, which covers only a few days, Alice has learned truths about her husband, her parents, her marriage, her family and herself, and has undergone a profound conversion in values. Because this is a Woody Allen film, a lot of that metaphysical process is very funny.

Mia Farrow stars as Alice, who has no apparent relationship to Alice in Wonderland but finds her own looking-glass in the dingy walk-up offices of the highly recommended Dr. Yang in New York’s Chinatown. He asks her to gaze into a spinning wheel while he hypnotizes her, and then he discovers, as he suspected all along, that her pains are not in her back, as she claims, but in her heart.

She leads a comfortable life, cut off from all sources of suffering and therefore also of joy. She and her husband (William Hurt) live in a Manhattan apartment that has been interior-designed to within an inch of its life. Also occupying their home, in supporting roles, are a cook (“I couldn’t get free-range chickens today!”), a nanny, and of course their small assortment of two children. It’s the kind of house where support personnel are constantly ringing the doorbell: Here comes the trainer now.

Alice has been married for 16 affluent years to Doug, a stockbroker played by Hurt as a kind of human deflecting machine, whose physical and verbal postures seem designed to avoid any kind of actual contact. He’s always changing the subject, usually into silence. One day Alice is taking the kids to school and drops a book on the stair, and the book is returned by a dark, handsome stranger (Joe Mantegna), and instantly she begins thinking about having an affair. The very notion shocks and thrills her, and after Dr. Yang (Keye Luke) discovers her secret, he gives her various herbal potions, including one to make her invisible, and another that gives her the knack of talking seductively.

What Dr. Yang has really done is to release her from all inhibitions, psychological and physical, so she’s free to range widely through her current and past life. She confronts her sister.

She has an imaginary conversation with her husband. She levels with her mother. She is even taken on a flight over Manhattan by the ghost of a former boyfriend.

The movie uses Allen’s unique style of off-center, fast-thinking dialogue, with throwaway lines and quick topical references. Everyone in the story is fairly smart, although some are in over their heads, like the Mantegna character, who cannot quite understand why this strange woman is first seducing, then abandoning him. A lot of the material in the film spins out of Alice’s childhood Catholicism; perhaps she still clings to a notion that some day she might become a nun, instead of a parasitic consumer of goods.

The world of “Alice” is the rich world of Manhattan, where the homeless and the poor are seldom seen. This is a world inhabited by countless stars in supporting roles, including Blythe Danner, Judy Davis, Bernadette Peters, Cybill Shepherd and Gwen Verdon. (The old boyfriend is played by Alec Baldwin, and is transparent in every scene. It is somehow typical of Woody Allen to obtain the latest box-office superstar for his cast, and then neglect to make him opaque.) The women in this world are intimate with boutiques, hair salons, chic restaurants and the interiors of limousines. Yet Alice can somehow not get the image of Mother Theresa out of her mind.

Perhaps if she went to Calcutta, if she became a follower of Mother Theresa, then would these vague stirrings of unease stop tormenting her? In a Woody Allen picture all such developments and U-turns are of course eminently thinkable, and one of the best things about “Alice” is that the characters are not linear creatures, hell-bent on moving in a straight line from the beginning of the movie to the end.

“Alice” lacks the philosophical precision of Allen’s “Crimes and Misdemeanors,” and the psychological messiness of “Hannah and Her Sisters,” and it also lacks the rigorous self-discovery of his underrated “Another Woman.” It’s in the tradition of his more whimsical films, like “A Midsummer Night's Sex Comedy.” And yet lurking in the shadows are some seductive questions. Wouldn’t it be wonderful if there were a man like Dr. Yang, a deus ex machina to drop into our lives with his herbs and paraphernalia, and lift the scales from our eyes, and free us from our petty routines and selfishness, and allow us to practice the sainthood we have always suspected lies buried deep inside?