Israeli director Nadav Lapid’s fourth feature is an imaginatively directed psychodrama about a director’s artistic and emotional crisis, done in the spirit of such navel-gazing auteurist classics as “8 1/2,” “All That Jazz,” “Day for Night,” and “Contempt.” That probably makes it sound simplistic and purely imitative, coming at the top of a review, but the comment isn’t intended that way. “Ahed’s Knee” is a fascinating movie that evades most complaints of not having anything to say by showcasing its characters struggling to explain free-floating anxieties that have to do with a lot of things. It’s also stylish as hell.

“Ahed’s Knee” observes a gifted but arrogant artist as he moves through the world and delves into his own psyche. The script’s fixation on the life and personal problems of the director, who is identified only as Y (Avshalom Pollak), is a binding agent, unifying what might otherwise seem like a bag of of half-formed political observations and quasi-poetic musings on Israel, its people, and their antagonistic relationship with Palestinians and Syrians, as well as the topography of Israeli desert landscapes, which are so strikingly envisioned that they seem to pulse with a life force of their own.

“Ahed’s Knee” follows Y as he works on a video installation partly inspired by the story of a teenaged Palestinian girl who was jailed for slapping an Israeli soldier. He then attends a screening of one of his movies at a library in an isolated desert community, where his contact is Yahalom (Nur Fibak), a beautiful young woman who organized the event because she loves Y’s films. Unfortunately for Y, Yahalom also works for Israel’s ministry of culture, an organization which—according to Y—determines “which books and plays are shown in Israel, and which writers, directors, or artists appear [in public] or stay home,” thereby controlling their creative and financial lives.

You’d expect “Ahed’s Knee” to make more of that last thing than it ultimately does, but there’s a lot going on in this film. It all leads back to Y, who guides us through the tale and sometimes “narrates” it in first person, by talking over images that represent flashbacks to Y’s past, or fantasies or stray thoughts he has in the moment. Sometimes the movie puts us in Y’s head by using the camera to show us what he’s looking at, from wherever he happens to be standing or sitting.

Lapid, who has a confident, expressive and constantly evolving visual style, uses a technique here that feels new: he starts a handheld shot with a closeup of the hero thinking or looking, then whips it over to a closeup of another character, a significant object, or some generalized phenomenon that his director’s eye finds interesting, such as the way pavement becomes a grey blur as you’re driving on a road. These “point-of-view” shots are typically angled in a way that suggests that we’re looking through Y’s eyes. But when the shot finally returns to Y, we’re looking at him again. It’s like when an omniscient novel switches from third-person to first-person and back.

There’s also a long sequence in film’s midsection where Y tells Yahalom about a disturbing incident that occurred when he was in the army during the war with Syria: his unit was trained to swallow cyanide capsules rather than risk being captured and tortured. The lighting and camerawork in these “flashbacks” feel different than the rest of the movie, to such a degree that you might wonder whose mind we’re in: possibly that of the listener, Yahalom. This would mean that the film has so much confidence in its all-over-the-place technique that it feels empowered to enter the heads of characters other than the hero, then return us to whence we came. (Cinematographer Shai Goldman and editor Nili Feller, both brilliant, amplify beauty while preventing the proverbial wheels from falling off the wagon.)

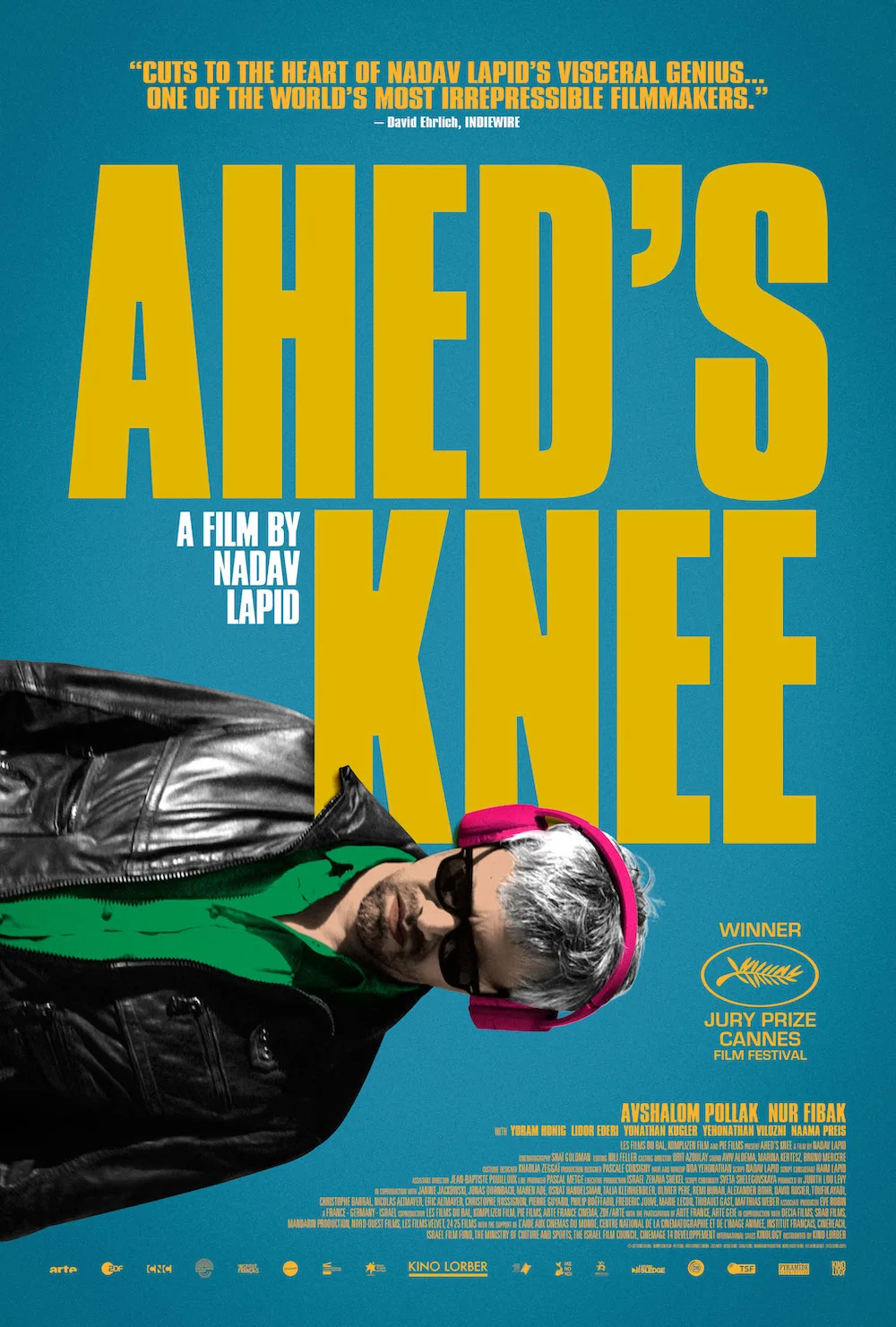

Y tries to convince others (and perhaps himself) that he’s the most interesting person in any given room by being manic, blabber-mouthed, and diva-esque. Lapid acknowledges how irritating Y can be by shooting some of his behavior in a way that suggests a toddler pouting after being told what he cannot do. There might be a self-critique buried in this character, who is embodied by Pollak with a quietly intense entitlement. For all his gifts, Y often comes off like a student who saw “8 1/2” at an impressionable age and decided he could be as cool as Marcello Mastroianni, especially if he bought the right pair of sunglasses (see photo at the top of this review).

The central incident in Y’s war story plays like a fusion of incidents from two works of fiction, Andre Malraux’s “The Human Condition” and Albert Camus’ “The Guest.” But like a lot of plot elements in “Ahed’s Knee”—including the relationship between Y and Yahalom, which progresses in a series of shots in which the actors’ faces are so close that you expect them to start making out—this one doesn’t pay off as you might expect. (There’s also a throwaway line from Yahalom suggesting that she thinks the story was filched from a novel, but is too respectful of Y’s distress than to come right out and say it.)

Overall, “Ahed’s Knee” is, to paraphrase a line from “The Limey,” less of a story than a vibe, but what a vibe it is. There’s really only one fully developed character in the film, the director. This constrains the film from being an all-time classic—even self-infatuated impresarios like Fellini, Truffaut, Fosse, and Godard surrounded their self-absorbed leads with lively secondary figures who seemed to have lives when they weren’t onscreen—but nevertheless, you can’t say the director didn’t do it this way on purpose. Y is somebody who sees others as a means to an end. Even when he’s making a show of being sensitive and a good listener, he’s still a culture vulture looking for scraps of experience he can transform into an arresting image or viable pitch.

More than one sequence departs from the movie’s stylistic baseline, a tough and gritty, international-indie-flick version of “reality,” and becomes as glossily viscerally as a Michael Bay action film (as in the opening motorcycle ride down rainy highways and streets, with huge flat raindrops quivering ion the camera’s lens). Other sequences use needle-drop music cues to set the stage for surreal “music videos” and impromptu dance numbers. The whole movie seems to be dancing. It’s fun to watch even at its most disturbing, and never funnier than when its hero seems mortified by the possibility that his own troubles aren’t the center of the universe.

Now playing in select theaters.