This Danish movie opens with a scene of high tension that soon situates the viewer exactly where he or she would never want to be. In Afghanistan, a group of Danish peacekeepers is scouring a patch of barren land, walking in a narrow, evenly-spaced line. The better not to get blown up by a land mine. Their work is methodical. The soldiers are in constant contact with their base, and its commanders and intel officers are providing calm, expert guidance. But of course something bad is going to happen. And something bad does happen, and the consequences weigh heavily on the commanding officer, Claus Pedersen. Out of a sense of guilt, and more overtly to make up for the absence of a shell-shocked soldier whom he’s decided to put on camp patrol, Pedersen begins accompanying his troops on their away-from-base rounds. He doesn’t know it, but he’s setting himself up for a fall.

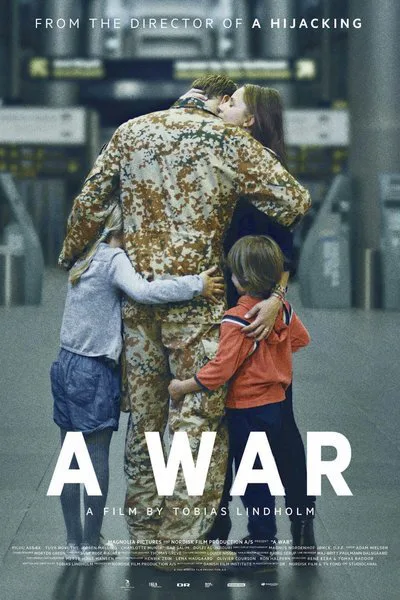

I’m being deliberately vague about the plot points of this gut-churning movie, written and directed by Tobias Lindholm, it’s because I truly believe, beyond any kind of “spoiler-alert” preemptive service-journalism second-guessing, that this is a movie best experienced more or less cold. Pedersen, beautifully portrayed by Pilou Asbæk, is a good man—a large portion of the movie’s first half crosscuts between him and his wife and kids in Denmark, and his devotion and care is almost palpable—and arguably a good soldier. But what does it actually mean to be a “good soldier?” “A War” asks this question in an understated but unambiguous way. The movie could take this ever-pertinent quote from Ernest Hemingway as its motto: “Never think that war, no matter how necessary, nor how justified, is not a crime.” Once Pedersen and his troops are lured, in a completely appalling way, into a brutal ambush, Pedersen takes action that ends up curtailing his tour of duty, calling him back to Denmark to answer for a war crime, weighing his own conscience against the dry dictates of a defense attorney who flatly tells him, “I’m here to create acquittals, not deal with moral or ethical questions.”

This is a movie where it’s extremely helpful to pay attention, especially during the ambush scene, because Lindholm places the viewer in a noisy, confusing predicament along with the soldiers. It’s difficult to keep track of what’s going on, let alone make an assessment of what you yourself would do in Pedersen’s place. And again, the consequences of what Pedersen DOES do are nothing less than appalling. Which side are you on? Which side is the movie on? Asbæk is such an appealing actor, and the smirks and pouts of the movie’s prosecuting magistrate Lisbeth Danning, played by Charlotte Munck, are portrayed as on the petulant side, but even here the movie maintains an even hand: her arguments are cogent, sane, humanitarian, not wrong. The quiet authority Lindholm brings to the portrayal of all the aspects of the story—the soldiering, the camaraderie, the domestic travails of Pedersen’s wife as she manages the mutating behaviors of their three young children, the bland yet imposing officiousness of the military tribunal—is exemplary, and puts me in mind of the definite but unimposing style of the Iranian filmmaker Asghar Farhadi, who deals with not entirely similar but nonetheless extremely fraught moral conundrums. “A War,” as tough to watch as it can be, is an extremely rewarding and disquieting experience.