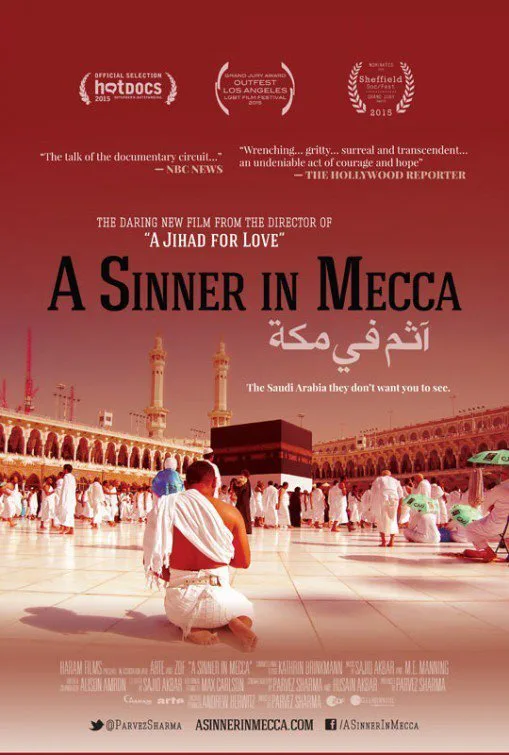

The trailer for Parvez Sharma’s new film, “A Sinner in Mecca,” with its pulsating music, tortured bodies, and scary news clips, depicts a sensationalism worthy of the most crass of Islamophobic films. The movie itself starts with a chat room conversation on a homosexual website with a Saudi who just witnessed an execution of a gay man. Next, Sharma performs a stylistic ablution dripping with blood, which seems far more melodramatic than dramatic. The rest of the film, however, calms down as his quiet, soft narration leads us through his performance (with emphasis on “performance”) of the Islamic pilgrimage, the Hajj. He seeks not to condemn Islam as much as he seeks to dig beneath the perceived politics, patriarchy and primitive behaviors to find it. It is a well-intentioned film that buries its affectionate heart in disjointed, unnecessary, forced banter.

Sharma distracts from what could have been a powerfully sentimental film by positioning his narrative in line with modern self-proclaimed Islamic reformers. Asra Nomani’s book “Standing Alone in Mecca” recounts her own pilgrimage, using the same narrative of the victimized sinning reformer who does not fit among the savage masses as well as she does among inclusive White culture. Here, Sharma shows the Muslims as nameless messy people crushing him during prayer, people from whom he fears for his life, while his White husband in the United States is a civilized concert pianist. Ayaan Hirsi Ali, far more rabid in her hatred of Islam and Muslims, calls for a violent overhaul of Islam to make it as secular European as is possible. I would wish that if people were going to call for innovative reformations on Islam, that they would at least be innovative.

Such authors seem to resort to sweeping vilification of Saudi Arabia with the usual tropes: public executions and rigid religiosity coupled with capitalist extravagance. They claim—as do most hypocritical Fox News talking heads as well as bottom feeding liberals of the Bill Maher, Sam Harris, Richard Dawkins variety—that the soul of Islam is the dark Wahhabi menace of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA).

It is true that the KSA approach to Islam dominates the Arabian Peninsula and has oil-profit funded tentacles across the globe. But, Sharma runs into a serious contradiction when he asserts that the main mosque in Mecca, run by the same Saudis, is the only mosque in the world where women and men are equals, side by side. Apparently, despite all the rightly-criticized problems of Wahhabi Islam (executing gays, demolishing sacred sites to build shopping malls, prohibiting modern cultures), they somehow lead the world in progressive gender dynamics?

The next problem here is the claim that he has to secretly film his whole adventure on his cell phone because of a ban on cameras. Spike Lee hired a Muslim crew to shoot footage in Mecca for “Malcolm X” (1992). Anisa Mehdi gave us a full film about the Hajj in National Geographic “Inside Mecca” (2003), which itself had older National Geographic footage from the 1970s. On this note, Haifaa al-Mansour’s stories of guerilla filmmaking her “Wadjda” (2013) in KSA are far more interesting because she had a whole crew and was a female; Sharma, in contrast, is an inconspicuous man in a sea of identically dressed pilgrims holding a single phone. Anyone who has been on the pilgrimage comes back speaking of the plethora of camera phones. I went on the pilgrimage in 1999 and a man told me of his experience circumambulating the sacred Ka’ba while listening to the poetry of Muhammad Iqbal from his Walkman. People today who should be worshiping are often capturing selfies, calling relatives, or taking photos. Despite signs warning against camera usage, there is plenty of camera usage. Despite Sharma’s claims, there is no controversy here. For proof, take a moment right now to google “Hajj Selfie.”

My true frustration about Sharma’s film is that beneath the diversions, it contains the material for what could have been something as controversial, powerful, and tender as he seemed to wish. After the film’s sensationalist beginning, he marries his husband. Writing as somewhat of a practicing Muslim preacher, frequently called to officiate weddings, I am not able to textually justify gay marriage. But, that stance does not grant me the freedom to wash my hands of something that is an existentially profound matter to some of my students. As I pour through scripture, scholarly discourse, and contemporary secular writings, I keep looking for serious answers to these serious questions. His previous film, “A Jihad for Love” (2008)—taking us into the lives of LGBTQI Muslims— touches on this need, while emphasizing the humanity of its subjects as they struggle with belief and culture. In other words, those who casually write off Marriage Equality as a blasphemy also ignore something that is central to a gay man or woman without providing a reasonable alternative. In Sharma’s current film, however, the result of his gay marriage seems to be that he has a travel buddy. His solution is a rehash of his solution in “A Jihad for Love”: the Sufis. Aside from the repetition (again, a lack of innovation), the Sufis themselves, whether in their Tariqah networks or in less-structured communities are often as rigidly dogmatic as their Wahhabi counterparts. The former might seem more communal compared to the capitalism of the latter.

Deeper than all of that, however, is the story of Sharma and his late mother. As Sharma reads their correspondences, preserved on fragile pieces of parchment, as he walks through the South Asian streets she walked, as he meets her old friends and neighbors, the manufactured drama of his pilgrimage vanishes and we find rudiments of a film that is as caring and tender as his voice. In it are the fixings of a story that any viewer—gay or straight, Islamophobe or homophobe—could relate to: he searches for his own validation through his search through her memory. I would hope that he revisits this story in the future, and that he lets the withered call for Islamic reform remain on hold until something novel comes along.