“A Man of No Importance” tells the story of a Dublin bus conductor named Alfie, whose hero is Oscar Wilde, whose hobby is staging amateur theatricals and whose nickname for the handsome young driver of his bus is “Bosie.” Since Bosie was also Wilde’s pet name for his lover, Lord Alfred Douglas, one could be excused for concluding that Alfie was gay. But the time is the early 1960s, when such clues were not easily seen in Ireland, and Alfie’s sister confidently waits for him to find “the right girl,” even though he is close to 60 and not exactly looking for her.

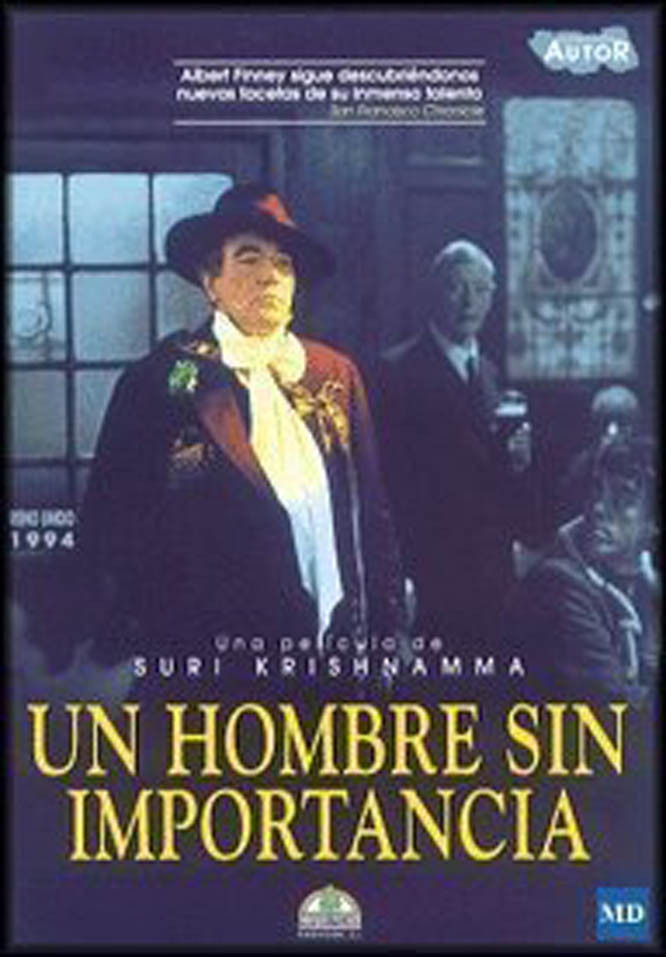

Alfie is played by Albert Finney in another of those performances where Finney inhabits his character as comfortably as an old slipper. Only Finney’s ease and confidence, indeed, make Alfie very believable, since the film’s story is more parable than reality.

This is another of those tales where we are invited to cheer as the protagonist at last understands and accepts his true nature, but while we are happy for Alfie there is no sense that much was really at risk; his safe landing is made clear almost from the opening frames.

What is best about the film is its sentimental portrait of a Dublin filled with such innocents and lovers of literature that the regular passengers on a bus could look forward to the conductor’s daily readings from literature – and would not complain when he delays the bus one morning for a young lady who might be the ideal lead for his production of Wilde’s “Salome.” The Irish more than many other societies live in a close proximity to their literature. On my trips there I have been surprised to find that Wilde, Shaw, Beckett, Joyce and the others are as familiar as football heroes or pop stars. I never met an Irishman who couldn’t quote a little Yeats, or more than a little. This helps lend some credibility to the notion that a bus conductor could cast “Salome” from among his passengers, something one would not attempt in Chicago on, say, the Clark Street bus.

Dublin is a big city, but Alfie lives in a small world, and we meet its inhabitants. There is Carney (Michael Gambon), the butcher, who often plays the lead; Lily (Brenda Fricker), Alfie’s sister, who doesn’t like it when he prepares fancy foreign dishes out of cookbooks; Adele (Tara Fitzgerald), the sweet-faced young girl Alfie wants for Salome, and Robbie (Rufus Sewell), the bus driver, who does not remotely suspect that the conductor has a crush on him.

Oh, and of course there’s the benevolent Father Ignatius Kenny (Mick Lally), who is happy to lend the church hall for the theatricals, although he may have a slight suspicion that Oscar Wilde lacks the imprimatur.

The movie finds a consistent vein of sly humor, indeed, in the inability of most of its characters to catch on that Alfie is gay – or that Oscar Wilde was. The story takes place at about the time of the Profumo scandal, when the society doctor Stephen Ward was accused of providing call girls for a British cabinet minister. Such is the confusion as this information arrives in Dublin that one perfect line of dialogue confuses Ward’s profession with his practices, and refers to “homo-a-pathy” as a sin.

Alfie is obviously on a collision course with his true nature, and the way in which this theme works itself out had best not be revealed here, except to say that Quentin Crisp would have been proud of the floppy hat and flamboyant pink scarf Alfie finds in his closet.

Barry Devlin’s screenplay has other good one-liners, as when Alfie defends Wilde: “It’s nothing to do with the Bible or nine weeks on your knees to St. Jude – it’s art.” Or when he has a moment of self-knowledge late in the film, after his sister says, “When I think of where your hands have been!” and he replies in anguish: “They’ve never been anywhere! I’ve never been close enough to anyone to so much as rub up against them, let alone put a hand on them.” And then adds with stubborn humor: “Me hands are innocent of affection.” All of this should work better than it does. I think the problem is that the director, Suri Krishnamma, is too easy on the story and the characters and, with the exception of one scene outside a bar, avoids the rough edges. The movie operates at the level of a literate sitcom, in which the dialogue is smart and the characters are original, but the outcome and most of the stops along the way are preordained. I said it was a parable, but perhaps it’s more of a fable: a story told after the fact, rearranging the details into the way they should have been.

If there were real Alfies in Dublin in the early 1960s, and I am sure there were, their lives were probably not anything near this cozy.