“A Hologram for the King” opens with a new greatest hits moment in Tom Hanks acting history. Set to “Once in a Lifetime” by the Talking Heads, he’s shown as a business man whose life has become a joke. As he talk-sings the opening lyrics à la William Shatner (“How did I get here?”) the film mixes images of his house, car and wife going up in purple smoke with a close-up of him riding a roller coaster, looking blankly at the camera. Hanks’ filmography is full of numerous mainstream performances, but this off-beat one takes viewers back to watching him meander around Steven Spielberg’s “The Terminal,” or stuck at a crossroads in Robert Zemeckis’ “Cast Away.” As Tom Tykwer’s adaptation of David Eggers’ novel proves, it’s entertainment just to stare back at Hanks.

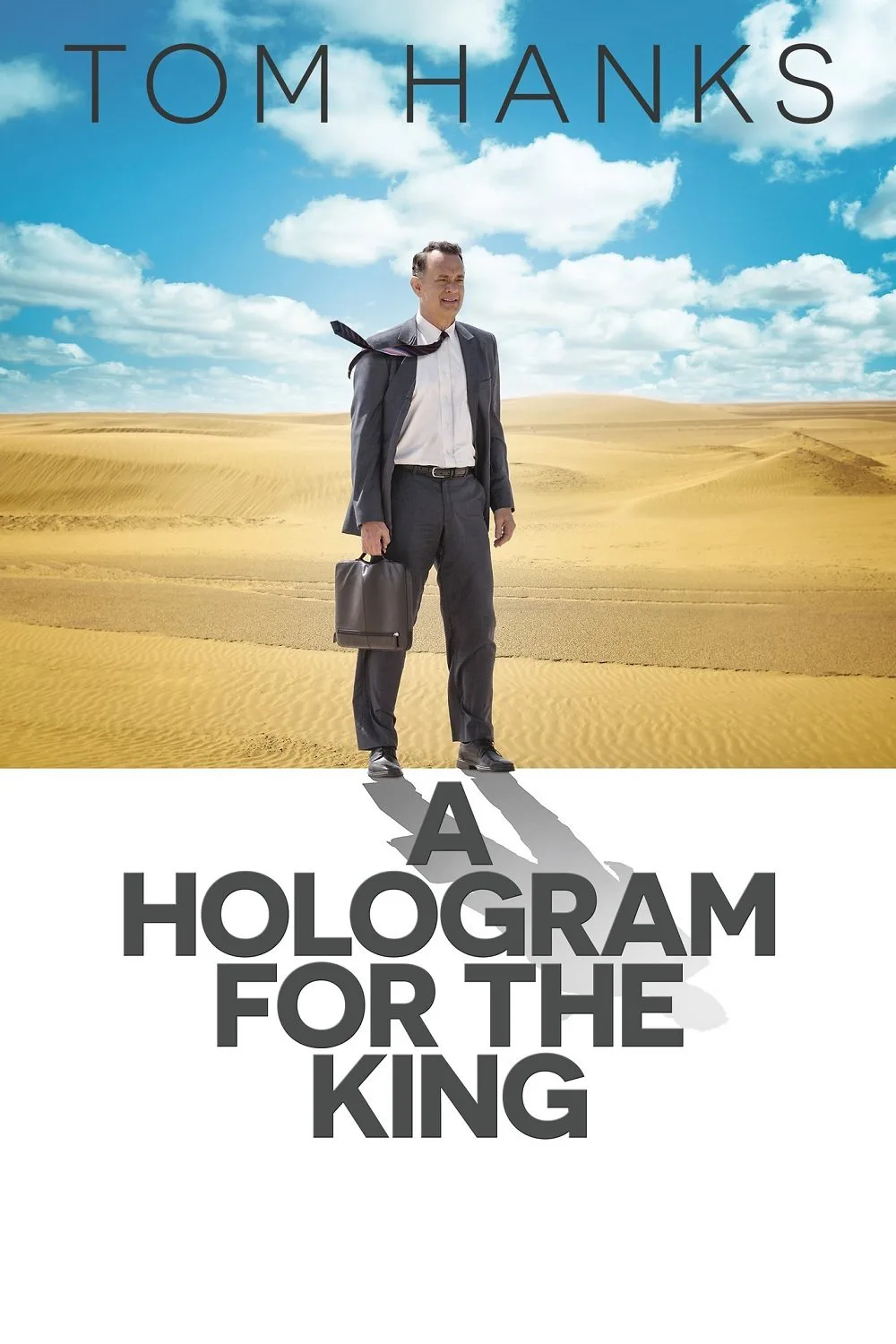

Here’s a reasonably-sized star vehicle that finds exciting purpose in presenting an existential crisis. The opening sequence is a dream he has on a plane while flying to Saudi Arabia, leaving behind his past life of tanking the Schwinn company when he outsourced hundreds of American jobs. Hoping to make the money to pay for his daughter’s college tuition, Hanks’ Alan Clay is now trying to sell a hologram contract to the king of Saudi Arabia, who wants to build a city in the middle of the desert that will populate 1.5 million people by 2025. The irony is hard to resist from the beginning—a former failure of empathy, now selling a machine for impersonal business, to an enterprise that may as well be a mirage, for a king who never shows up. Alan has to travel an hour every morning from the city to the project’s headquarters, only for a receptionist to tell him that the king is not in. The strange stresses pile up as his business trip becomes a seemingly endless, yet highly amusing farce: Alan’s small tech team is stored in a tent but have no Wi-Fi, AC or food. Perhaps by no coincidence, a giant bump suddenly appears on Alan’s back.

The cycle that the king’s indifference places Alan into leads to a poignant truth behind our own dark clouds, our partial responsibility to push back against the negative forces of nature overwhelming us. Clay misses his shuttle to the king’s headquarters because he somehow oversleeps each morning, which in turn forces him to call upon his driver/impromptu cultural guide Yousef (Alexander Black). Almost midway into the film, when Alan decides to defy the receptionist’s demand to not venture past the lobby, he breaks the cycle. He gets upstairs and people know his name, as if they had been expecting him to sneak up there all along; actions against his bump yield similar results. In a feat of invested storytelling and performance, Tykwer’s strange movie makes these minor changes seem huge.

It’s a disappointment, then, when “A Hologram for the King” transitions this anti-fatalism into a succession of epiphanies you can get wholesale. As the narrative changes from a fascinating circle to a flat journey for Alan to find his new self, it drags to metaphorical checkpoints, like when Yousef drives Alan off a different path, and later when Alan is face-to-face with a wolf that is about to attack some sheep. As it slowly devolves into another mid-life-crisis-abroad tale, the movie’s charm starts to evaporate.

After many car ride scenes and wide open shots of the desert, Tykwer injects a highly visual romance into the third act. One can imagine that aside from this story touching upon his interests in the passage of time, the very passionate storyteller (“Run Lola Run,” “Cloud Atlas“) wanted to see a man and a woman swimming underwater, in a bright blue water that directly contrasts endless sand. But even as poetic defiance towards a nation that publicizes executions more than displays of affection between the opposite sex, Tykwer can’t match the previous exhilaration of Alan’s isolation.

The people Alan interacts with closest are sporadically intriguing, with two performances that make clear efforts to expand beyond script devices. Black’s Yousef has a naturally progressive camaraderie with Hanks, which Black treats with friendliness and occasional animation (despite being, like with Christopher Abbott’s Fahim Ahmadzai in “Whiskey Tango Foxtrot,” more white-washed casting). Sarita Choudhury has an expanding part in Alan’s life as his doctor, and brings a sincere delicacy. The film’s most distinct character remains the king’s new city, which says just as much about his Godot-like presence when shown as abandoned, skeleton-like skyscrapers with people living inside.

Hanks remains a great everyman, which means here he can be a wonderful outsider, a surrogate into our realizations or failures. To Hanks’ credit, the actor is also able to find empathy for a recession-era villain; every time Tywker randomly cuts back to the disturbing silences of Alan’s past life (standing in front of hundreds of workers, about to make a horrific announcement), our heart sinks with him. In some scenes he makes us laugh (when his chairs break, three times); in many others he simply welcomes us to feel small with him. Alan is one of Hanks’ less-flashy roles, but it largely confirms why we’ve made him such a central figure in American film acting.