When Erik Nelson’s documentary “A Gray State” opens, we’re on the set of an indie film-in-the-making watching its good-looking young director commanding the cast and crew in front of him with both ebullience and authority. While the scenes being staged look uncommonly violent for a contemporary drama that’s not in the horror genre, the set is full of the high-spirited energy you often see on low-budget movies. But, having seen enough of this on screen and in life, I sink into my seat thinking: “Is this really what I’m about to watch—a doc about making an indie feature?”

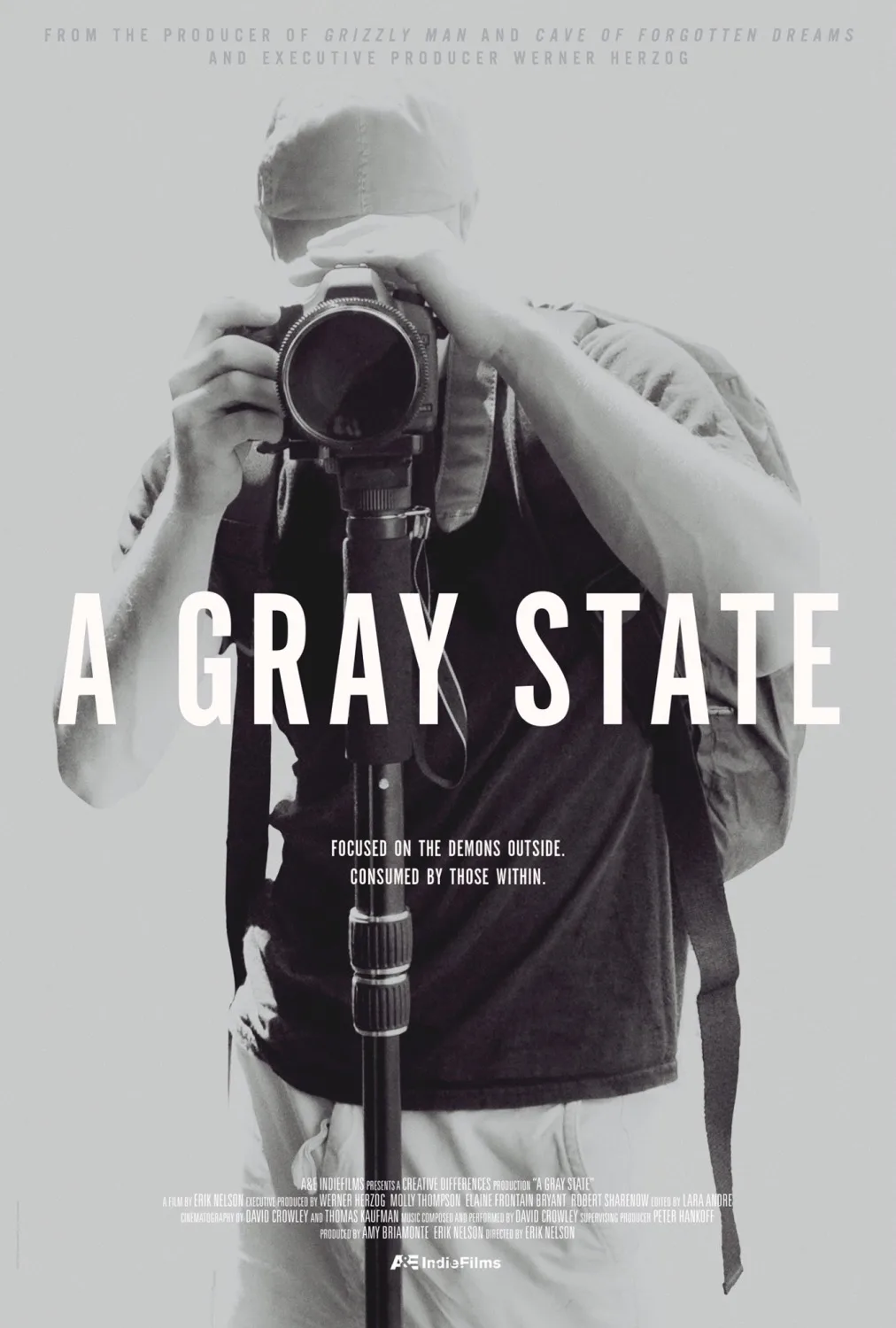

Well, no. “A Gray State” quickly becomes a very different film. The director we’ve watched is named David Crowley, and he was actually shooting footage for a trailer of a feature he intended to make titled “Gray State.” Envisioning a terrifying future where government armies crack down on the U.S. and are resisted only by scattered partisans, the trailer was a great success on social media, making Crowley a celebrity to Libertarians and Tea Partiers and helping him crowd-fund a screenplay. But the feature never got made. Instead, police who found a horror scene at Crowley’s Minneapolis home in January 2015, determined that he had killed his wife and five-year-old daughter before turning the gun on himself.

Filmmaker Nelson previously acquired the raw materials for the documentary “Grizzly Man.” Though he initially intended to direct the film himself, he saw the advantage in turning over the directing to Werner Herzog, and he produced. Herzog returned the favor by executive-producing “A Gray State,” which has a couple of notable similarities to its predecessor. Besides looking into strange cases that ended in violent tragedy, both films make use of copious video footage left behind by their subjects.

In the last four years of his life, David Crowley was a man obsessed, and one of his obsessions was recording his own life. Nelson was thus able to craft his narrative from hundreds of hours of video plus innumerable selfies and audio and written documents. Also, in addition to interviewing many of Crowley’s friends, family and filmmaking colleagues, he showed or played some of this material for them. Their reactions are sometimes as illuminating as the materials themselves.

After the Crowleys’ tragic demise, some of his admirers on social media began charging that the deaths were “mysterious” and suggesting he was killed by a conspiracy that didn’t want “Gray State” to get made. This opens up various narrative avenues and speculative directions that Nelson might have pursued, but he chooses not to. Rather, he notes these dark suspicions early in his chronicle, before turning to examine what really led to the tragedy.

David Crowley seemingly was a typical young Midwesterner who grew up playing army games and carrying guns. His best friend says that in high school they just assumed they would go into the military, and so they did. They shipped off to fight in Iraq, where Crowley saw people killed and began developing deeply distrustful views of the U.S. government.

Back in the U.S., he fell in love with and married a Texas Muslim dietician named Komel, who apparently converted to Christianity. Though ready to settle into married life, and believing his overseas military duty was done, Crowley was shocked when he was ordered to Afghanistan. Back in the war zone, he experienced what we hear called a “breakdown.”

On returning to civilian life, he entered film school while Komel worked to support them and their young daughter, Raniya. It’s worth noting that politics didn’t draw Crowley to filmmaking but vice versa. His dark suspicions of the government may have infused his vision for “Gray State,” but his ambitions were like those of many film-school grads. Seemingly surprised by the strength of the reactions to his trailer, he increasingly gravitated to the right-wingers who supported him, yet his main goal was a familiar one: Hollywood.

He went there looking to convert his screenplay and social media success into a $30 million movie, and Nelson interviews two executives who liked him and were interested in backing him. They found him a straight-up good guy, bright and articulate. Then Nelson plays them an audio tape on which Crowley laid out his plans for seducing them in the pitch meeting. The guys look shocked. They say the words indicate a guy who was “manipulative” and “insane.”

In the following months, no movie got made. Instead, Crowley drew further and further from friends and family, though his mental spiral—including new occult interests—apparently included Komel. When her worried sister drove 17 hours from Texas to see her, she wouldn’t come out of the house.

Then there’s the chilling bit of home video where little Raniya fantasizes about the walls being splattered in blood. Watching it, one interviewee says, “It’s definitely like ‘Redrum, ‘redrum’—‘The Shining.’” Another person offers another apt cinematic analogy—”Sid and Nancy.”

By coincidence, I write these words a day after being in lower Manhattan near where an apparent ISIS-inspired terrorist killed eight people before being shot down himself. Later in the day, a friend and I reflected that such incidents, once virtually unknown, now are almost weekly occurrences. And whether they’re deemed to be perpetrated by lone nuts or adherents of some violent ideology, they often seem to reflect the media-generated spread of collective fantasies and a kind of toxic narcissism that characterizes the era of selfies and social media.

“A Gray State” captures much of this in one real-life tale that’s as unsettling as it is precisely of-the-moment.