Having met Peter Greenaway, I find it easier to understand the tone of his films. Not a lighthearted man, he is cerebral, controlled, is so precise in his speech he seems to be dictating. “He talks like a university lecturer,” I wrote after meeting him in 1991, “and gives the impression he would rather dine alone than suffer bores at his table.” Yet there is an aggressive, almost violent, streak of comedy in his makeup; one can imagine him, like Hitchcock, springing practical jokes.

Consider a scene in “8 1/2 Women,” his new film. It takes place in a staid Swiss cemetery. His hero, Philip Emmenthal (John Standing), is a billionaire who has just lost his beloved wife. He arrives at the services dressed in a white summer suit because his wife disliked dark clothing. He is informed that a black suit is absolutely required according to the bylaws.

Enraged, defiant, stubborn, Philip grimly strips down until he is standing naked on the gravel; observing the letter of the law, he demands even black underwear. He is surrounded by minions who lend him their own clothing–a black shirt, black tie, pants, coat, even underwear (“it looks like a swimming suit,” its wearer explains, “and I was hoping to go swimming later”). His decision has forced his employees to strip as well, and now, dressed in black, he walks a few feet to one side and we see what we could not see before–that the preacher and all of the mourners were waiting nearby, in full view of everything.

Now how is this funny? Trying to imagine other kinds of comedies handling the material, I ran it through Monty Python, Steve Martin and Woody Allen before realizing it has its roots in Buster Keaton–whose favorite comic ploy was to overcome obstacles by applying pure logic and ignoring social conventions or taboos. Keaton would have tilted it more toward laughs, to be sure; Greenaway’s humor always seems dour, and masks (not very well) a lot of hostility. But, yes, Keaton.

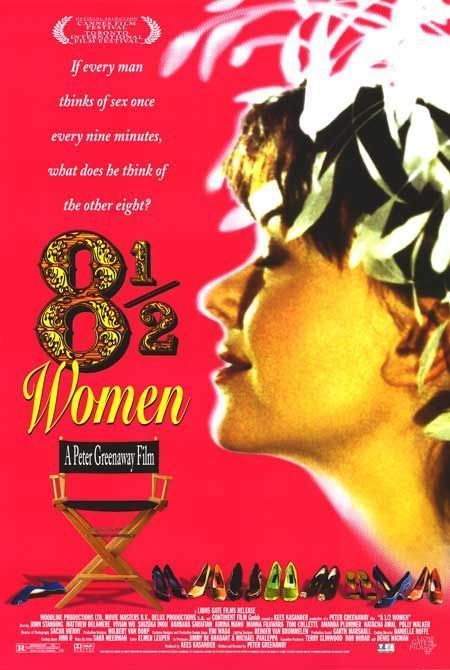

One possible approach to “8 1/2 Women,” I think, is to view it as a slowed-down, mannered, tongue-in-cheek silent comedy, skewed by Greenaway’s anger and desire to manipulate. The movie’s title evokes memories of the ways Greenaway numbers, categorizes, sorts and orders the characters in his other films. His titles like “Drowning by Numbers” and “A Zed and Two Noughts” show the same sensibility; he distances himself from the humanity of his characters by treating them like inventory.

Here, however, real emotion is allowed to fight its way onto the screen. Philip is in genuine mourning for his dead wife (“Who will hold and comfort me now that she’s gone?”), and his hopelessness moves his son Storey (Matthew Delamere). There is a scene, offscreen but unmistakably implied, in which they have incestuous sex, perhaps as a form of mutual comfort, and many scenes in which Greenaway, so interested in male nudity, has them naked in front of mirrors and each other. This is not the nudity of sexuality, but of disclosure; a billionaire stripped of his clothes (and his Rolls Royces and chateaus and servants) is just after all a naked man with flat feet and a belly.

Father and son have been involved in a scheme to take over a series of pachinko parlors in Kyoto, Japan. Pachinko is an addictive form of pinball, much prized by the Japanese. They meet a woman who has gambled away most of her family’s money on pachinko, and are surprised to discover that her father and her fiancee both suggest she sleep with Storey (or Philip) to work off the debt. (This does not represent a loss of honor, the translator explains, because the Emmenthals are not Japanese, thus do not count).

This woman becomes one of the first of eight and a half women the father and son move into their Geneva mansion, in an attempt to slake their grief with the pleasures of the flesh. All of the women are willing participants, for reasons of their own–the one in the bizarre body brace, the one unhappy unless she is pregnant, an amputee who only counts as a half, and so on. Greenaway deliberately does not build or shoot any of the movie’s many sex scenes in a revealing or erotic way; they are always about power, manipulation, control.

Apart from the father’s real scenes of grief, the film is cold and distant. It shows its bones as well as its skin; some of its shots are superimposed on pages from the screenplay that describes them. It is not possible to “like” this film, although one admires it, and is intrigued.

Greenaway does not much require to be liked (is my guess), and what he is doing here has links to deep feelings he reveals only indirectly. At two times in the film, father and son watch Fellini’s “8 1/2,” particularly the scene where the hero gathers all of the women in his life into the same room and tries to tame and placate them. After the second viewing, the father asks the son, “How many film directors make films to satisfy their sexual fantasies?” “Most of them,” his son replies. This one for sure.