Tekashi 6ix9ine has the words “six nine” tattooed over 200 times on his body, one of many ways the hardcore rapper has dedicated his entire being to a love-or-hate presence. And yet the Hulu documentary “69: The Saga of Danny Hernandez,” which is all about his career choices, is not the kind of attention that he wants (his Instagram remained silent to his millions of followers after its release). That’s because it’s the comprehensive treatise we’ve needed about such an enigmatic, problematic figure, especially when it comes to understanding the full extent of his artifice. The documentary vigorously investigates—and subsequently calls out—his integrity as an artist, an associate, and even as a gang member.

“69: The Saga of Danny Hernandez” is not about a star, then, but a black hole. There’s so much to this story—so many crimes, so many in-your-face rap singles—yet it’s all for the vacuous goal of attention. Director Vikram Gandhi avoids getting lost in this mess by focusing on the people who witnessed Hernandez’s transformation into a rapper named Tekashi 6ix9ine, but it’s fascinating to see how Gandhi’s feelings about the artist change from the beginning (he initially thought he was making a cautionary tale) to the end. Ever since seeing this Fat Joe interview, in which the legendary rapper tries to get through to Hernandez, I’ve wondered if there was something more to Tekashi 6ix9ine. But with his damning journalism and thorough documentation of Hernandez’s real-life gangster activity, Gandhi chips away at such sympathy and alters how to look at someone who wants to always be seen.

Gandhi tells this story chronologically, breaking it up into different sections: “The SoundCloud Rapper,” “The King of New York,” “The Troll.” Before all of that, there’s “Daniel the Bodega Boy,” which paints a picture of a Hispanic kid growing up in poverty in Brooklyn, living with multiple family members in a tiny apartment. When he was a teenager, he was traumatized by his stepfather’s murder, which fueled his desire to get out of the neighborhood, and to be famous. He got a taste of that fame by wearing shirts and hats that caught people’s attention, with words like “HIV” printed on them in big letters. Music became an extension of that, especially after he saw how his friends gained popularity through rap videos. Through a complicated history of working with one artist after the next, Hernandez launched a rap career as Tekashi 6ix9ine through over-the-top videos, involving him renting out Lamborghinis and showing himself in sexual acts, realizing the viral audience that came with bizarre visuals. At one point he was charged with a sexual offense involving a video with a 13-year-old girl and served time for it, but being labeled a “pedophile” by his haters didn’t exactly slow down his career.

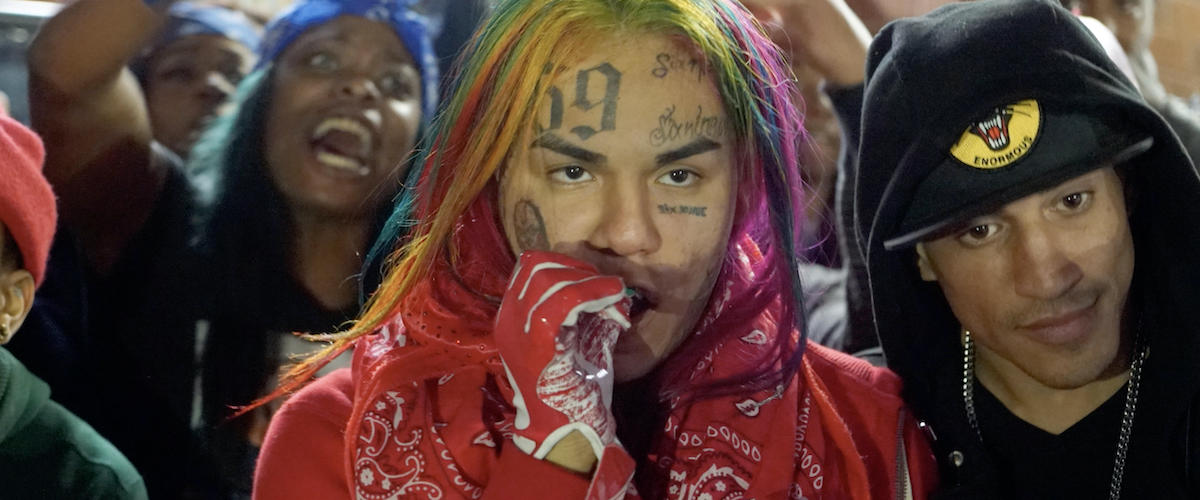

Hernandez ascended in a changing music business that seems to encourage using collaborators and haters for clout, and mixed that knowledge with his growing awareness of what gets eyeballs on social media. It’s a tactic that goes back to Elvis and Ozzy Osbourne, as Gandhi’s guiding voiceover instructs us at one point, but has become even more viable in the era of social media, though the landscape is far more crowded. For such a visual musician, with his long rainbow hair and all those tattoos, the young rapper found his best medium on Instagram, and screaming YouTube videos like “Billy” and “Fefe” are two-minute bursts of aggression that sell Hernandez as a real-life Joker. There’s a realization in listening to his music that the songs are primarily designed to give him something to do on stage, or in a music video, or to simply promote. To quote Tekashi 6ix9ine: “My music is trash but my videos are fire.”

The first act of “69: The Saga of Danny Hernandez” runs a bit slow as a history lesson, even though like much of the documentary it provides a great deal of context about someone who would rather have the slipperiness of an online super villain. Gandhi’s film picks up when it starts digging into certain parts of Hernandez’s career and gaining access to the reality of Hernandez’s work, providing a necessary delegitimization. One of the best moments involves a breakdown of the bombastic video for Tekashi 6ix9ine’s “Gummo,” which used the Bloods’ red bandannas as a prop, provided to real gang members by Tekashi himself, even though at the time he wasn’t in the gang. Gandhi interviews one of the film’s extras, a matriarch who tells a personal story echoed throughout: she at one time welcomed Hernandez into her home for Thanksgiving. But when he was done with them, he disrespected her and her family, and left. We also learn of the horrific abuse he inflicted on his long-time girlfriend, a counter image to the family man he posits to be on radio interviews.

For anyone worried that the documentary might still be a roundabout way to promote Tekashi 6ix9ine’s discography, Gandhi skips over releases and milestones to instead detail the gang activity that became a more direct expression of Hernandez’s narcissism, control, and need for an audience. After hooking us with some image analysis, Gandhi then immerses us in a Scorsese-worthy saga about Hernandez achieving power through the Nine Trey Bloods gang and their top members, who helped give Hernandez a more robust presence, and physically act on his public beef with rappers like Trippie Redd or Chief Keef. Along with providing more background to what one of the most famous rappers at the time was doing behind the headlines and viral Instagram posts in 2018, these passages also have talking heads illuminating how much different and less aggressive Hernandez was when he wasn’t using violence for a social media audience. It becomes clear that this bluster is all some type of show, even when it later gets him arrested for racketeering and weapons charges, leading to an infamous court deposition where he betrays everyone else’s loyalty.

There’s a certain pointlessness to intellectualizing this stuff, and the artistic void of Hernandez’s music and tragic psychology create its own type of nothingness at the center of Gandhi’s narrative. A modern addiction to fame is as real as it is hollow, and the documentary would feel more robust if it engaged more how why we want self-avowed trolls like Tekashi 6ix9ine to entertain us. The project’s existence almost offers more clarity when you look at it as not a coincidence in Gandhi’s career—he previously made “Barry,” about a hopeful America and a young Barack Obama, and now he’s made a counter documentary about a destructive leader obsessed with his popularity numbers, hellbent on selling a grandiose version of themselves, while a cult of personality sees such narcissism as a reflection of power.

How do you solve a problem like Tekashi 6ix9ine? You really can’t, especially by making a documentary about him, and Gandhi finds that out in the process as his approach shifts from sympathetic and curious to vigilant deconstruction. But for an artist whose court deposition is one of his most honest career moves, “69: The Saga of Danny Hernandez” is affirming as a reality check built from image analysis. Gandhi has essentially made a biopic about a toxic persona, and proves there isn’t much more to Hernandez than that.

Now playing on Hulu.