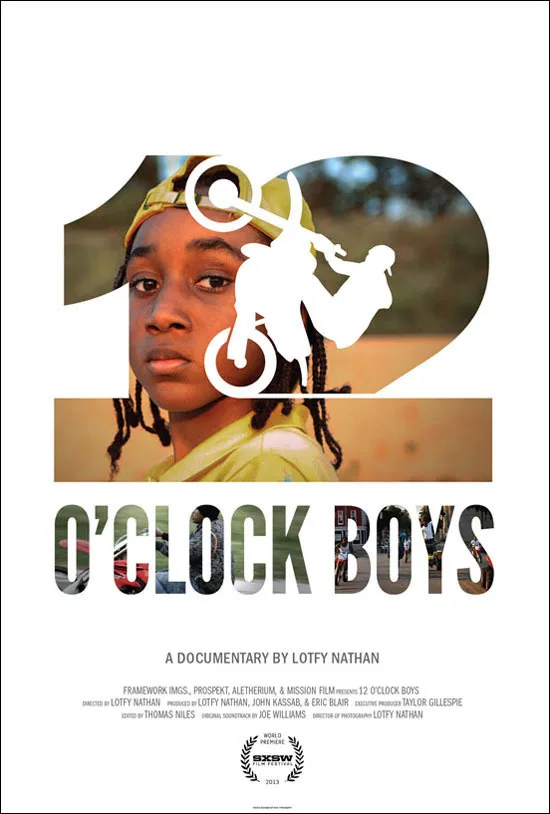

A thin, problematic and amateurishly-made documentary, “12 O’Clock Boys” plays like two films awkwardly grafted together. One documents the criminally boisterous antics of the eponymous Boys, hundreds of young African-American men (most appear to be in their late teens, 20s and 30s) who ritualistically roar around inner-city Baltimore on loud motorbikes, ignoring all traffic laws, endangering the citizenry and defying the police, who have little chance of impeding the rampant law-breaking since they’re forbidden to give chase due to concerns over public safety.

The other film, meanwhile, is a verite-style portrait of Pug, a cocky, cute and exceedingly camera-friendly inner-city 13-year-old, whose troubles at home and school find a welcome escape valve in his adulation of the Boys and desire to join their ranks.

Given the film’s title, you might expect the first of those elements to dominate, with Pug’s tale being a unifying thread that runs through the narrative. But that’s not the case. The footage of the Boys (much of it from the cell phones and video cameras of onlookers) mostly comes up front, sometimes interspersed with bland TV news reports about their public disturbances and the cops’ unavailing efforts to deal with them. Thereafter most of the film is devoted to following Pug’s life, which often has little or nothing directly to do with the Boys.

If this imbalance seems curious, a couple of reasons for it are readily evident. First, once you’ve seen 10 minutes or so of the Boys doing their police-baiting wheelies and other stunts, you get the picture; jaw-dropping as it sometimes is, much more of it would quickly become redundant and tedious. Second, as the film’s young director, Lotfy Nathan, told Rolling Stone, he didn’t want to make an “issues film.”

“Issues films,” and the “talking heads” they often entail, have become increasingly unfashionable on the documentary festival and art-house circuits, for reasons that are worth examination and discussion. Suffice to say here that, in choosing to avoid such an approach, Nathan radically limits his authorial options and thus the avenues of understanding he offers viewers regarding the film’s titular subject.

As a result of this choice, while we see the Boys roaring around Baltimore, we get very little sense of who they are as individuals or the context in which they operate. We hear nothing from community leaders, black or white, much less experts (talking heads!) on this milieu or such automotive sociopathic behavior. Though we are told that the Boys’ dangerous exploits have resulted in the death of one child, the attitudes resulting from this in the community are barely touched on. And naturally, the police are given no voice at all.

So if he’s not making an “issues film,” one that would include various points of view and enough information to challenge the viewer with the complexity of its subject, what is he making? Well, clearly: an entertainment film. And a very specific type at that: a film by a white filmmaker (it’s very hard to imagine “12 O’Clock Boys” made by an African-American) that spectacularizes black criminality for white middle-class viewers, the primary audience for the festivals and art houses where this film will have its career.

Surely, criminality isn’t the sum total of this tale. There’s a scene where a black adult takes a group of kids out in the country to ride their dirt bikes and ATVs, and here we get a bracing sense of what an exhilarating escape from their hemmed-in normal lives such jaunts are. But would the film be in theaters if it contained only this kind of law-abiding outing? For that matter, would it be garnering such warm reviews if the criminality it depicted were committed by white Long Island lunkheads, or Texas rednecks?

Running a scant 72 minutes, “12 O’Clock Boys” still feels twice as long as it needs to be. One can imagine interesting ways Nathan could have extended it to feature length. For example he might have shown it to Jesse Jackson and asked his reaction. Or Bill Cosby. Or Coretta Scott King. Or Michelle Obama. But of course such comments almost surely would have done the one thing that Nathan’s approach can’t afford to do: problematize the film for white viewers by allowing its own (white) viewpoint to be challenged.

Indeed, this itself might have made for a far more interesting film. To me the doc’s most intriguing passage comes in its first minute, when, over a shot of Pug looking particularly puppyish, we hear the voice of a white man (presumably on a radio call-in show) opining that the problem of “little scumbags on dirt bikes” terrorizing parts of Baltimore can’t be frankly discussed because the perps are black. Presumably Nathan regards this as a completely unacceptable view, and puts it up front simply in order to dismiss it. But what if it had opened the door to a discussion throughout the film about the issues the comment raises, including how a film like this one uses its subjects for entertainment value rather an inquiry into social dysfunction, and the question of whether white people who imagine their view of the Boys to be tolerant and sympathetic (even hip and fashion-forward) are not in fact being patronizing and demeaning? I’m not suggesting any ready answers to these questions, simply that it would be good to hear them asked.