Twenty years ago this month, a documentary about high school basketball players premiered at the Sundance Film Festival: “Hoop Dreams,” produced by Chicago’s Kartemquin Films and directed by Steve James. The critical support of Roger Ebert and his TV sparring partner Gene Siskel transformed it from a local film by unknown directors into an art house success that would later be regarded as one of the great American documentaries of the 1990s.

It seems fitting that two decades after Roger helped breathe commercial life into “Hoop Dreams,” James would return the favor by adapting Roger’s memoir “Life Itself,” and that it would premiere at Sundance, a festival that Roger’s attention helped legitimize.

In addition to telling the story of one man’s life and career, “Life Itself” recounts the decay of Roger’s body in the final months of his life, after the cancer he’d battled for years returned with a vengeance; it includes medical scenes of great frankness, filmed with the encouragement of Roger and his wife Chaz, this site’s publisher. The result is a testament to the fragility of flesh and the transformative effect of love. More than anything else, it’s a record of Roger’s generosity, the effects of which are still being felt.

I talked with James last week. A transcript follows. — Matt Zoller Seitz

MZS: How long ago did you start talking to Roger about the possibility of adapting his memoir “Life Itself”? What was the timeline for production going to be originally, and how did that change with the resurgence of his illness?

SJ: Well, actually this is a project that was brought to me by [writer-director] Steve Zaillian and his partner in his production company Garrett Basch. Steve had read Roger’s memoir. Steve’s a big doc fan. He just thought it would make a great basis for a documentary. Garrett first reached out to me and asked if I was interested.

I knew of Roger’s memoir. I don’t live completely in a cave. But I hadn’t read it. I quickly read and just thought, “What a great book and what a great project.” I said “Yes, I would love to do that.” And they were optioning the book so they had been in touch with Roger and Chaz about it. So they floated my name by Roger. And Roger gave me the thumbs up, as it were.

My first conversations with Roger were via email to just tell him that I was really excited about being a part of it. And his question back to me was, “Well, why do you think this would be a film, and what makes you want to do this?” Kind of like what you’re asking. [laughs] And so I emailed him back at some length with my thoughts about why this would be a great story and an important story to tell, and my ideas about how I wanted to go about telling it.

That dialogue eventually ended up with a meeting that Chaz suggested. We had it at their home, where I talked a bit more about what I had in mind…Essentially the film that I made is similar in a lot of ways [to what I proposed], except that we ended up filming him for the last four months of his life.

I did have every intention of filming him in the present, and at that time it was to show just how incredibly vibrant he remained despite all that he’d been through; that he was still going out to screenings, having dinner parties at their home, attending events and festivals. So I really kind of saw the stuff that I would film in the present as a spine that would along me to spring to the past, kind of in the way that he does in the memoir itself.

He’s consistently coming back to the present and then going off. I copied that for the movie, and I used the book as a real, serious major source. He had chapters devoted to guys like [Ebert’s longtime friend, newspaperman] Bill Nack, so I wanted to interview Bill Nack. He had chapters devoted to Martin Scorsese and Werner Herzog, so I wanted to do that. And there were other people featured in the book who don’t get chapters devoted to them, but who nonetheless start to loom pretty importantly, like [filmmaker] Ramin Bahrani.

There’s a quote fairly deep into the film, taken from the book, about time “slipping through our fingers like a long silk scarf.” And there’s a quote from one of Roger’s blog posts talking about his grandkids, and talking about the past when the kids were younger and he was more mobile. He says “Those times seem more precious now because they’re in the past. I don’t walk easily anymore.”

I had all these ideas of things I wanted to shoot with Roger, and one I was dying to shoot with Roger. There’s a moment in the memoir when he talks about looking in the mirror today, and what he sees is not the face that he has now but his face from as a child and as a young man. And I was like “Wow, let’s get that shot. I’m going to have him looking in the mirror and use that as one of these springboards for the past.” It was one of my favorite ideas that I didn’t get. I had this idea that I was going to see him going to a screening. I was going to go to some lengths to shoot a shot where I’d have the camera mounted outside the car and you’d see the cityscape reflected across his face. I had all these ideas, many of which I didn’t get.

But part of the reason that I love doing documentaries is that you start with ideas—and you hope good ideas—about what it’s about and who you’re following and all of that, but if it’s a really great experience it always deviates and deepens as it comes, and is more interesting than anything you could imagine. Because if I could imagine that well, then I should be doing more fiction than docs.

You do a version of that mirror shot, in a way, simply by observing Roger’s physical decline at the end and his heroic attempts to delay it or battle it. You kind of get into this idea of the body as a husk or a shell that is gradually going to fall apart. What are we left with? The contents of our minds, our imagination. The great bulk of the film’s running time is comprised of that.

Sometimes I mention to people that we were there in the last four months, and they haven’t seen the movie, so their first reaction is ‘Ohhh.’ You know. And it is sad. I think there is plenty of sadness about this film, But I’ll tell you the thing that struck me about him in those last four months is that he was courageous enough to show us the sides that weren’t so beautiful and wonderful, he and Chaz both.

That’s putting it mildly. I know that from having corresponded with Roger. He was upfront about the state of his health, on his blog and in emails to friends.

But it’s another thing to actually see it. That’s another thing entirely.

I was just really struck by that, and by the spirit. One of the first shots I shot of him, he was asleep, and it was almost like my first image of him asleep. And I just remember my reaction. I had not seen him except in public settings, and my reaction was “Oh my God.”

But then he woke up and he smiled, and it was Roger. And that sense of humor was there, that sharpness. Everything that people know of Roger in his public persona was all very much in evidence in those last four months.

One idea that Roger returned to again and again in his blog posts—and it’s sort of alluded to in that image that you were trying to film, the shot of his face—is that when he looks in the mirror he doesn’t see the Roger that he was at the end, he sees an intact Roger, or a younger Roger. It reminded me of something my grandfather said to me when I was a teenager, and that probably every older person has said at some point. He said, “On the inside I’m still nineteen.”

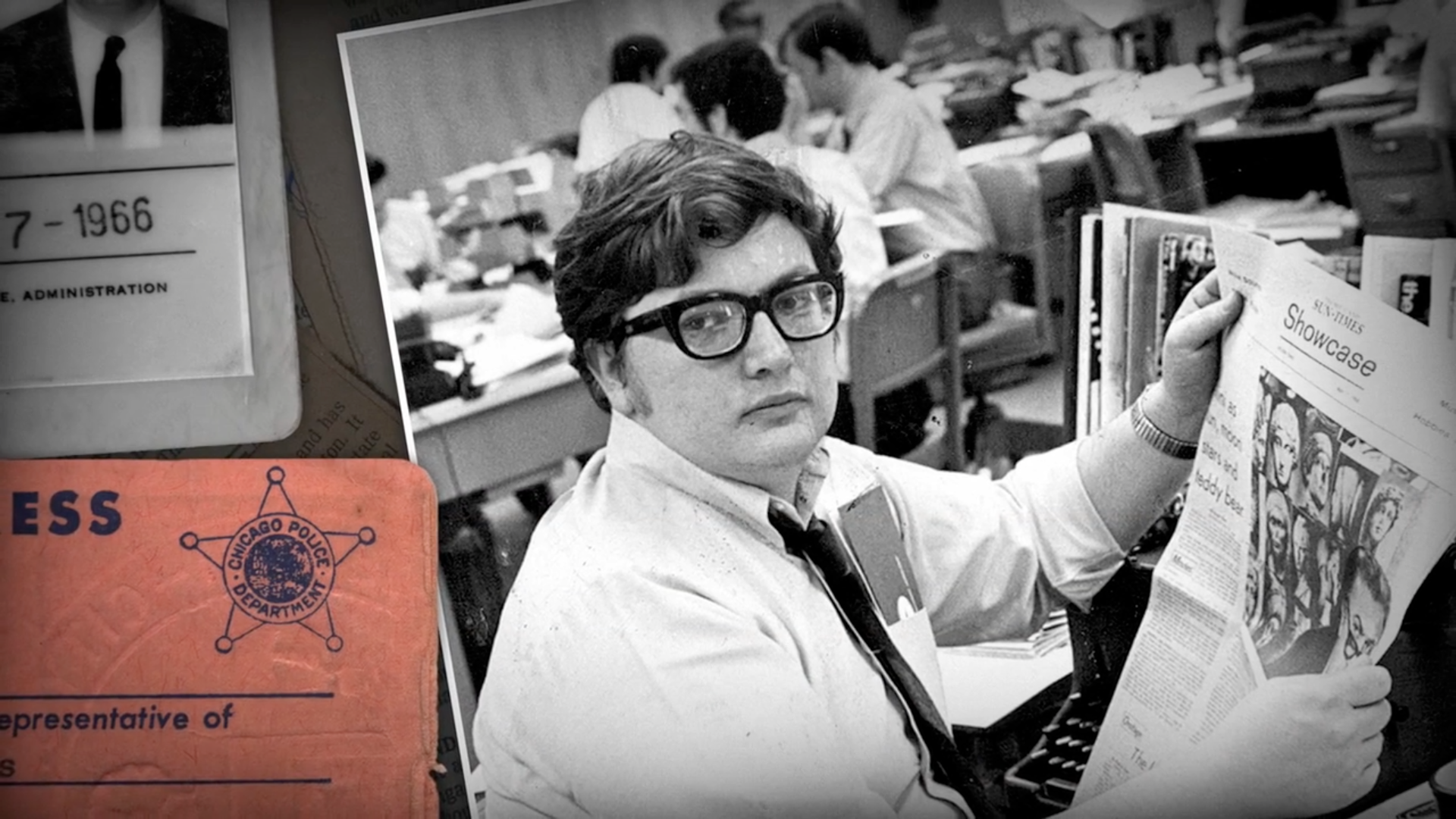

I feel like that comes through with your portrayal of Roger, and particularly with the excerpts from the book and the way that they’re integrated with all of these photographs of Roger from all these phases of his life, including his childhood.

Yes, the level of cooperation that we had from Roger and Chaz was amazing in terms of them digging and allowing us to dig into everything that they had to put in the film. And it extended to Roger and Chaz emailing people that I wanted to interview, by way of introduction, and saying please cooperate, and please be candid.

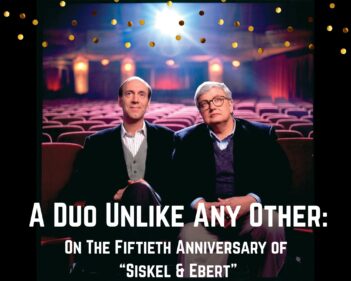

There’s a lot of talk about the fact that Roger could at times be not a very nice guy, and there’s also a section of the film that discusses whether the success of his movie review show with Gene Siskel was a boon or a detriment to film criticism.

I wouldn’t have done the film if I didn’t have admiration and even more for Roger. Even the people in the films I’ve made who aren’t in any way, shape or form completely lovable, I have to have affection for them to do the film. It’s too hard.

At the same time, I’m not looking to do hagiography either. It was important to me to make a film that shows why Roger was important and why he was a great man, but also to show him as a three-dimensional, flesh-and-blood human being. Because to me, that journey he went on in his life that he talks about in his blog was a journey operating on a number of levels, and one was that he did some profound growing up as he went along. Some of it came pretty late in life.

And it’s not that he wasn’t a great guy—everybody loved him…well, just about everybody loved him. But he did some serious growing up later in life. And Chaz was obviously a part of that.

The film actually pinpoints the age of that delayed growing up as fifty, and I believe that’s how old he was when he married Chaz. And there are quotes to the effect of him mellowing after he met Chaz.

Doesn’t Gene Siskel’s widow talk about Roger jumping in front of her to get a cab when she was eight months pregnant, in the pre-Chaz era?

And she’s saying he’s not that kind of guy anymore.

And there’s also a generosity to Roger that the movie captures very well, and that you see in the selection of key interviewees that you’ve put together. I made a list of the people interviewed, and I realized that they’ve all had their lives profoundly effected, positively, by Roger.

There’s Martin Scorsese, who is almost moved to tears as he recounts how Siskel and Ebert’s giving him an award when he was depressed and going through a career lull inspired him to keep going. And then you have A.O. Scott, who was certainly doing well already, having been named one of the New York Times’ film critics, before he met Roger, but who did not start to become a national personality, a recognizable figure, until Roger put him on a new version of the old show he once did with Gene Siskel. You’ve got so many other people who tell those kinds of stories.

And you’re one of them too. You’re like Errol Morris, in that you could almost say what he says in the movie: that he wouldn’t have a career if it wasn’t for Roger.

In fact, Errol’s story about “Gates of Heaven” in many ways parallels “Hoop Dreams.” And frankly, I was really thankful that it did, so I didn’t have to feel seriously consider whether to put “Hoop Dreams” in the film. I didn’t want to put “Hoop Dreams” in the film, even though if anyone else had made this film they might have put it in, because it was a fairly celebrated example of the power of Siskel & Ebert, and of Roger in particular, and his incredible ability to champion new films and filmmakers. I was so thankful.

There were so many filmmakers—and I suppose I knew it but you really see it making the film—filmmakers who felt like that about Roger. I love Ramin Bahrani’s story about Sundance. And certainly Roger went on to be a huge champion of Ramin’s work, even to the point of giving him that precious puzzle.

Yes, Roger takes a puzzle that once belonged to Marilyn Monroe and hands it off to a filmmaker!

It’s a testament to Roger that you did have a number of people to choose from who can tell you those sorts of stories. You’ve got Gregory Nava and his movie “El Norte.” You use that as one of the first examples of Roger and Gene deciding to have the dog wag the tail instead of the other way around, and review a movie on their show that wasn’t playing very many places yet, and thereby stimulate curiosity around the country as to when people could see the movie, which in turn led to bookings nationally. It was a way for them to use the TV show as clout, in a positive way.

That’s why the argument about the impact of the show on film and film criticism is important. It’s complicated enough that it deserves a full hearing. That’s one of the reasons I wanted to put it in there.

I had [Time Magazine film critic] Richard Corliss speak to that, and [Chicago Reader film critic Jonathan Rosenbaum speak to that, and I think they do a great job of presenting what they see to be the downside to the show. But I also think absolutely a great answer to that argument is Nava, and Morris, and these other cases in which they took these films that were obscure when they came out and put them on a national show, when you could only see them in a few places.

He did that with “Hoop Dreams” when we were at Sundance, which is the most extreme version of reviewing a film that no one can see. I think Gene said in their first TV review of it, “The only people who can see this are the people who are at the Sundance Film Festival.” But they went on to say in the segment that the film deserved national distribution. They were very upfront about it.

They started doing that shockingly early in their television career, too.

Yes, with “Gates of Heaven” it was 1978, so that was two years into the show—before they’d taken off, really. That’s the thing about the show. I watched it when I was younger, when I first got interested in film, and my first thought was “why do these two guys from Chicago have a show about film?” Because I came at it like a lot of people, reading Andrew Sarris and Pauline Kael, and thinking it was all in New York or France. And it was more curiosity when I first tuned in, looking at these Chicago guys.

But in the course of doing this film and going back and looking at the old shows, I was amazed at how bright a piece of television it remains. Even in this fast-paced, bored-in-a-millisecond culture, it’s great television. If you had those guys doing that show today, it would be different, of course, because of the internet, but in my mind there’s no question that it would be great television.

Their personalities were so strong, and they were, over time, comfortable on camera.

And they were so intelligent about it. And it’s fascinating to go back not just to the films that are well remembered, but also to the ones that have kind of faded. Sometimes I am there with Roger, sometimes I’m with Gene. Maybe some people had their favorite, but I would bet that part of the show’s appeal was that you didn’t tune in to root for Roger or Gene in the argument. You tuned in because they were both making really smart points and different points, and sometimes you found yourself agreeing with one, and sometimes you found yourself agreeing with the other.

Can you tell me what it is like as a documentary filmmaker being witness to intimate moments like the ones you photograph in this movie? Particularly the hospital stuff, where you have Roger having his throat irrigated right in front of you.

And you have this extraordinary moment which…I’ve got to say, I’ve never seen a moment in a film that hit me so hard as a revelation of what it is like to care for a sick person as that scene where Roger doesn’t want to get out of his wheelchair and go up the stairs into his house. He’s sitting there, and you’re shooting him from behind, and he’s scribbling on his notepad and he’s jabbing at his pad and you can see how angry he is. It’s just painful to see, because we have all had a friend or a relative in that situation.

SJ: Part of what makes it so distinctive is it’s something we rarely see in films even if we’ve seen it in life. The other thing that makes it distinctive is, it’s a really famous guy. This is not someone the film is introducing you to who you wouldn’t have known otherwise. This is Roger Ebert.

I was the one shooting that part. There’s a part of me that, as a good cameraperson and filmmaker in that situation, I of course want to get around to the other side, and be on the other side of Chaz and Roger, so that I can see their faces, not the backs of their heads. But I knew better than to say, “Oh excuse me, could everyone move out of the way so that I can get the shot?” Because that would have been wrong to do personally.

But I was also amazed at how powerful it was, even without seeing their faces. As you said, it was clear what was going on and how people felt. And I remember thinking “Are they going to ask me to stop? Is Chaz going to turn around and say ‘Steve, turn the camera off’?'” And she didn’t. Sometimes after the heat of a moment is past, people will come to me and say “Gosh, that was embarrassing to me.” Neither of them said that to me.

And Chaz had plenty of opportunities in the aftermath, after Roger’s death, when we were editing, to say to me, “You know, Steve, I’ve been thinking about that moment, and would you consider taking that out?” She didn’t have any editorial control or approval on this project, but she never even brought it up as a consideration. She did say, just before I showed part of it to her, “Is that scene in the movie?” and I said yes. And she said “Okay,” and that was it.

You don’t lose anything by not seeing their faces. In a way it becomes more universal, because you’re not seeing faces, you’re just seeing a hand. The focus of your attention is on Roger’s hand jabbing, and not only do you sense the anger and the frustration in him, but it stands in for what’s happening to him in a larger sense. He’s lost his physical voice. Everybody talks about how he lost his physical voice but he never lost his writer’s voice. Yes, hooray for Roger, that’s great. But on the other hand, if you’re trying to argue with your wife, it helps to have an actual voice. The movie is aware of that in a very human way, and that’s touching.

Another favorite moment of mine, and it’s a bit lighter, is when he’s getting suction and he wants to put on Steely Dan. And Chaz is just…’Can we just do the suction?’ And he’s not listening. It’ s like he’s a man on a mission. He wants that music playing while he gets the suction, and I just love that.

And Chaz in voiceover right around that point in the film talks about his will and his spine of steel and stubborn determination. And I think that’s important, because I think that’s part of who he was as a person. He was used to having his way, except for with Gene, and that’s where the alchemy happened. It’s also that will that saw him through all this, with Chaz’s enormous help. That will and determination were what saw him through.

I don’t think it’s any accident that the two filmmakers he was closest to over the years were Scorsese and Herzog. One of them directed a film about a guy determined to drag a steamship over a hill so he can build an opera house. And the other, every movie he makes is about an obsession that the hero can’t let go of.

Including “The Wolf of Wall Street“, which I just watched last night. That’s three hours of obsession.

Talking about the footage of Roger’s health problems and the decline near the end, he did give you something like a mandate to shoot that? It almost seemed like that was important to him, and you have a quote from Roger in the film, via an email he sent you: “It would be a major lapse to have a documentary that doesn’t contain the full reality. I wouldn’t want to be associated. This is not only your film.”

But he didn’t have any kind of editorial control over it, did he?

No, not at all. Just as we were just about to get underway, he emailed me and said, you know, I’ve explained to Chaz that this is your film and we will not have any say in this. I don’t think she was asking for that, but I think he wanted to prepare her that, “This isn’t like our show, where we control things. This is going to be Steve’s film.”

But I emailed him back and said something that I’ve said in different ways to all the subjects in all my films. I said “Roger, I appreciate that you understand that. But what I also want you to understand is that I really view the filmmaking process with the main subjects in a very collaborative way. I want to hear from you. You already understand that so I don’t even need to say it. But yes, you will not have editorial control of the film, but I view it as a collaborative undertaking in the sense that I can’t do it without you and I really do want to hear from you, and I will show you the film before we are done.”

Of course it didn’t happen, but I said it also to Chaz: I will show you the film before it’s done so that you can tell me what you think and I’ll at least hear you out on it. And I think he actually really liked that. It allowed him to say some things like that email that you quoted, understanding that he’s not in control but that he still had opinions.

I do think of films that way. I don’t think of myself as a straight-ahead journalist who goes and documents things and then says, “Here’s the finished thing.” At Kartemquin, that’s just not really our philosophy of filmmaking.

There’s one line in my notes I keep coming back to, and it’s the last line of that email I read earlier: “This is not only your film.”

Roger is no longer with us, so we can’t ask him, but what do you think he meant by that?

I took it that this is… You have to understand how I mean this… There will be other people who will make films about Roger Ebert. There very well could be a dramatic film. You could make a great movie about Chaz and Roger. There are a lot of things that could be done. I don’t want to be presumptuous to assume that this is ‘the one,’ but this is the first one. And I think in some ways Roger started from a place of not being sure that a documentary should be made at all. This is my speculation, but I think that when he got on board with it he realized that this was going to be some kind of definitive portrait—good, bad or indifferent—and that he wanted it to be everything that he would have wanted it to be, both as subject and as a critic.

When I was making this film, I kept thinking of him on my shoulder. I’d think what would he want a film about a guy like him to have in it? He wouldn’t want it to be painting him as Saint Roger. He wouldn’t want it to be hagiography. He’d want some of the messiness of his life in there, because that was what would appeal to him as a critic.

I’m rambling, I guess, but I think that line was about that: “This could be some kind of definitive portrait in film of my life, and I want it to be definitive not just with what you, Steve, think is important, but also what I think is important.”