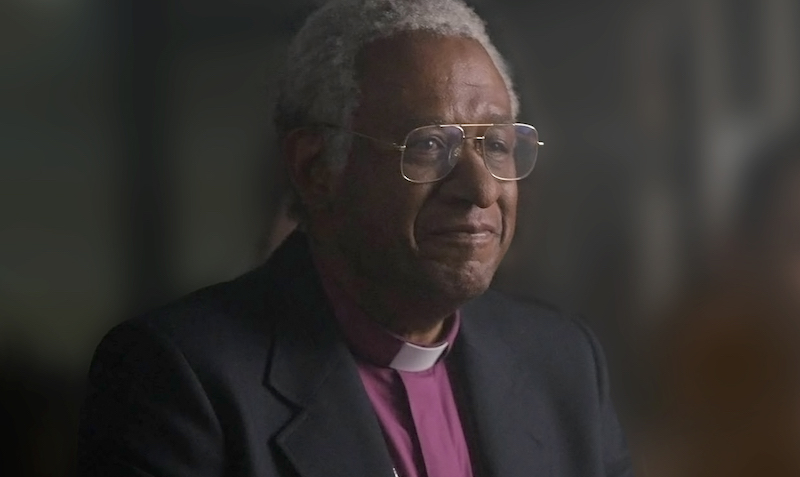

The legendary Forest Whitaker has always been a strong fit for historical roles, whether it was his work as jazz musician Charlie Parker in Clint Eastwood’s “Bird,” his Oscar-winning turn as dictator Idi Amin in “The Last King of Scotland,” or White House butler Eugene Allen in “The Butler.” With Roland Joffe‘s “The Forgiven,” Whitaker adds the charismatic, wise Archbishop Desmond Tutu to the list, using the actor’s contemplative and soft nature to recreate the events of post-apartheid South Africa, when Tutu was assigned with running South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission. “The Forgiven” dramatizes the story of Tutu and the case of Piet Blomfeld, a white supremacist South African (played by Eric Bana) who was responsible for, and gloats about, the gruesome killing of black South Africans. Lead by Tutu’s belief in forgiveness, the film aims to show the complicated nature behind Blomfeld’s deep hatred, while recognizing the struggle by someone like Tutu to see humanity in someone who has committed so much evil.

RogerEbert.com spoke with Whitaker over the phone the night after the Oscars about “The Forgiven,” the success of “Black Panther,” the wisdom of Desmond Tutu and more.

Did you get to have any fun last night, with the Oscars?

Last night, I had dinner, that was it. I had a good time, I was with my daughter.

I’m curious, given your history with the award, as to what the Oscars mean to you now?

It’s a special night where artists come together to celebrate each other’s work. I think personally it was quite an overwhelming experience, and the current Oscars are looking to have inclusion and to make statements in a way about the things that are going on in society right now … to have positive messages of believing and hope and standing up for what you believe. It’s a mixed bag of things, I think.

With “The Forgiven,” what new challenges did you face playing Desmond Tutu?

I resolved to just try to find and capture the spirit of the man. I think there are some physical differences that exist, but hopefully if I’m able to capture the spirit of him, that you’ll be able to recognize him inside of me. That was a challenge to just build positive energy and acceptance, that was a tough thing to work on. I worked on it throughout the film.

This film shares a striking similarity in message with another upcoming and real-life role of yours, Reverend Kennedy in the Sundance film “Burden,” where you play a preacher in who chooses to love and later protect a white supremacist. Is this an intentional choice for you to get these types of nonfictional characters out there?

I think it is important to recognize that we have to choose love. And I think that both of them, they’re both spiritual men who care deeply about humanity and how people are being treated well by humanity. And they battle it in different ways, but they both try to see past … I think that they’re going through similar challenges in the sense that they’re having to look past what someone has done, the negative flaws that someone might have done. In the case of both of them, characters who have done horrific things towards people of color, and try to find a place of forgiveness.

I think in “Burden” he says that if he doesn’t deal with this, if he doesn’t allow a person to be healed, to be OK, that he can’t preach anymore. That he can’t follow his faith, what he stands for. Nothing. I think that dilemma that Blomfeld puts Desmond Tutu through is a real one, where he has to question in some ways if he can forgive, even while listening to someone in a way revel in others’ pain, and the horrors he has conducted among others, and still find a space in his heart and mind to care about him, and to love him. But I think Desmond Tutu doesn’t believe that anyone is pure evil.

Going through Tutu’s life, and his actions, were you ever surprised by his extent of humanity? Do you think you would react the same when facing such hate?

I would like to try, I would try. It would be hard. I think he dedicated his life to those beliefs, and he believes that particularly for South Africa, he speaks about it, without forgiveness there is no future. And then how do you turn that around and shift it without turning it into another space of hate? He says that forgiveness is the key. God forgives, and so can we. I don’t think he excuses people, though. He definitely doesn’t excuse people. The thing about Desmond Tutu is that he’s a pretty aggressive activist.

And it seems crucial to understand Blomfeld’s story, his history and how his trauma in this narrative plays out; to understand where his hate comes from.

I think that’s important. And I think Roland Joffe recognized … I think the key [is] that we all come from a common source, but the experiences in our lives, we become different things, you know? And it’s that common source, that kernel, that private life of who you are, that is what made Desmond Tutu able to believe in humanity. He realizes that at the core of who you are there is a purity that I’m connected to as well.

You were a supporter of “Black Panther” director Ryan Coogler from the very beginning with producing “Fruitvale Station.” Were you at all surprised that he was able to translate that heart and that soul from “Fruitvale Station” into something as massive as “Black Panther”?

I’m not sure that I could know how deeply the film would move itself to the culture, and become some ways a movement, an expression for people of empowerment. But I think that I did have the feeling that the movie was going to do unbelievably well, you know? I did have the feeling that it would match some of the other “Star Wars” and other films. I did feel that way; I thought something special was happening. I know Ryan and I know Ryan is a great filmmaker with a great mind, and I think given the proper tools which he was allowed to utilize, and a great cast and a great crew, that he would be able to do something exceptional and that people would want to see that. And I think people would want to see that. I believe in Ryan and he has a great conscious, and he really cares about human society, and community. I think it’s reflected in the film, and people get it.

Given what we’ve talked about concerning humanity and Ryan Coogler, do you think being a good person is central to being a worthwhile artist? To believe equally in love and people? Is that essential?

I think there are artists throughout history who have questionable character. I don’t know if it’s essential … I think it’s a quality we need right now in our society. If the artists have a voice and they can connect and talk to so many people, and right now people are looking for some form of solidarity to feel that they are together and actually can make a difference. I think the messages we make in our films are important because they reflect our society, and also reflect the hopes for our society. We have to, as artists, take into consideration our own humanity and how it connects with others. I think Desmond Tutu says, “We’re not truly human alone. We are only human together. My humanity is bound up in yours.” I think it’s important for artists to realize what they can say and what they can do to help move the needle towards a more positive world.