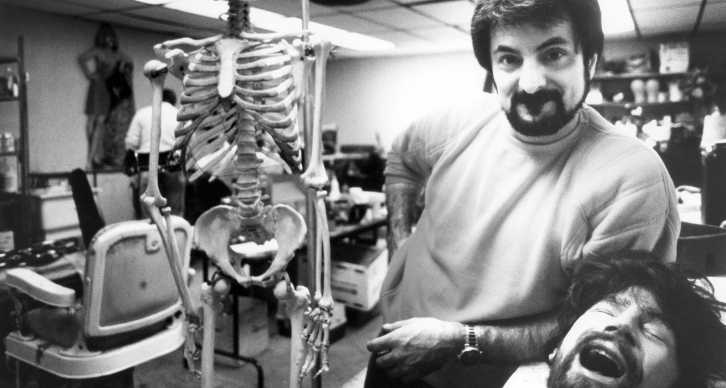

Special-effects wizard Tom Savini is most famous for his collaborations with fellow Pennsylvanian George Romero, whose “Night of the Living Dead” and “Dawn of the Dead” are still two of the most influential modern horror films. But Savini’s work as a character actor and director continues to inspire new generations of horror fans. Savini—a Vietnam vet who received an unprecedented fellowship from Carnegie Mellon’s acting and directing program—continues to oversee a school for aspiring make-up artists in Monessen, PA (which has been open for almost 18 years now).

RogerEbert.com spoke with Savini about a variety of topics—including his 1990 “Night of the Living Dead” remake, his animatronic “Robo-Chimp” puppet for “Monkey Shines,” and his three year-old grandson—in time for the Metograph and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences’ recent “An Evening with Tom Savini” event.

On your “Knightriders” audio commentary, you say that the summer that you worked on that film was the best because got to play with swords and ride on motorcycles. You also related a story about how you and a couple of other cast mates figured out a way to get into the headspace of your characters who turn on Ed Harris’ protagonist. For my readers, Harris was, in real life, trying to quit smoking, so you guys showed disdain whenever you caught him smoking. Is it fair to say that that was a formative experience, in terms of helping you to get inside a character’s head?

Yeah, you’re always looking for something to hang your character on, and that was a big help. All the knights got together and were talking about how we’re going to have to turn on him. Because we don’t know Ed, we only know the character of the king, and we knew that this was really George Romero’s biography. All his friends will tell you “Knightriders” is about George Romero. Because of that we thought, “Well, why don’t we like you? Why are we against you? We’ve got to figure out something. You have any foibles? Any weaknesses?” Ed says, “Well, I’m trying to quit smoking.” And we said, “Well, that’s the end of it. If we catch you smoking, we don’t like you.”

I know a lot of horror fans talk about your Romero collaborations as the films that get them into horror and your work. But my introduction to your work was on the kid’s TV show “Ghostwriter.” I wonder if you can talk a little bit about working on that show, especially creating the creepy little monster doll Gooey Gus.

They hired me out of the blue and that was great fun. We shot that here in New York. I brought my 9 ½-year-old daughter to that; she’s in it a few times. It was just fun to be … any excuse to be in New York for a long period. That’s what “Maniac” was about. I made no money on “Maniac.” I think five grand was what I was paid to do all that stuff and play the part, but I just wanted to hang out in New York for a couple of months. “Ghostwriter” fit that bill. As for Gooey Gus: it was fun to make a cartoon character after making all these horror characters.

A lot of your monsters and special effects are realistic, thanks in no small part to the fact that, as a former Vietnam vet, you hold your work up to a higher standard of realism. I also read you describe your work on “Maniac” as “the closest I’ve come to cold-blooded murder.” I wonder if you could talk a little bit more about working on that film. There’s one effect/scene that’s always stuck with me, where [character actor Joe Spinell’s] character shoots a shotgun at a couple in their car.

Well, the couple is me and an ex-girlfriend; I actually did the firing. I shot both barrels of a shotgun with magnum pellets through the windshield. I mean, I’ve never fired a shotgun through a windshield before. I blew another point like that in “Dawn of the Dead,” and I knew I could do it, but I never did it through a windshield. And when I fired the gun I flew backwards off the car. Somebody caught me, and they immediately put me in a car and drove me away. The gun was given to some policeman and he drove it away. We stole that shot. You’re not allowed to fire a gun in New York. There was nobody there sixty seconds after we did that effect.

Oh, wow.

I had made a mask of myself and we were sitting around talking about the effects in “Maniac,” me, Joe Spinell and [director] Bill Lustig. And I said, “Well, I do have this mask of myself. Why don’t I play a character where we blow his head off?” I took the mask and did a plaster lining and we filled it with all the food from the craft service table. There was four cameras on the shot and then, kablam. It was gorgeous. But you asked me something before that about … something before that effect with Joe Spinell?

Just about what working on “Maniac” was like.

Well, I couldn’t wait to meet Joe Spinell because I saw him in “Rocky” and “The Godfather.” I did a horror convention in New York before we started shooting and I said to Joe, “Hey man, I’m doing a convention and Caroline Munro is there!” I said that to him because I know he did “Starcrash” with her, and I was sure he wanted to see her. So he came to the convention and listen, Joe Spinell took me everywhere. He took me to the Friars Club; he took me to meet Sylvester Stallone on the set of “Nighthawks.” We were pals, we were hanging out. So he came to the convention, saw Caroline, and from that second on, Caroline Munro was the lead in the film and not Daria Nicolodi, Dario Argento’s wife.

We’d have meetings about the effects, and I kept having to check Joe. I kept having to say, “Joe, we’re not going to bite that off of a woman.” I remember saying that. There’s a misconception that I didn’t like the people involved with the movie and that’s not true. I want to emphasize that that’s not true. In interviews talking about “Maniac,” I said the subject matter was trash; even the people involved in it would tell you that. It was a trashy B-movie. People thought I was talking about the people and I was not. I loved Joe Spinell and Bill Lustig and everybody involved with the film. I want to make sure that’s part of this interview. I am not talking about the people, I’m talking about the subject matter of the movie.

It was great fun sitting around with Joe and discussing what to do. I’ll play the disco bully, I’ll blow my own head off. We created the effects in Bill Lustig’s apartment in a couple of days and then we started shooting the movie.

Your contract eventually required you to control the direction of your kill scenes and your makeup effects. Is there an experience or experiences that led you to acquire that, or was that just common sense for you?

I have a book out called “Grande Illusions” that’s all about the makeup effects I’ve done in my movies. I think of them as magic tricks. Now some directors don’t know how to create a magic trick. There’s misdirection, like, let’s take this axe and make it take a chunk out of a wall or knock out a lightbulb, with a real axe, before the rubber one comes in and embeds itself into a girl’s head, like in “Friday the 13th.” That’s a magic trick. The angle is critical as far as creating a magic trick. It’s a special effects illusions. This is what I tell my students in school. I have a makeup and special effects school in Pittsburgh that I’ve had for 18 years. My students have worked on – name a motion picture in the last 15 years, my students have worked on them. Or math companies, toy companies, labs … the mindset I tell them they have to have is, “What do I need to see to make me believe that what I’m seeing is really happening?” And then you show that to an audience.

You create the pieces to make what you’re seeing. It’s exactly what a magician does. A magician makes you look up here and he’s pulling flowers out of his butt. He’s misdirected you. There are a lot of mechanical devices to pull that off. So I would say most directors … not all of them, there are some directors who are really in tune with the effects being magic. There were only a few contracts where I insisted that I direct a scene with my effects man because I’m creating a magic trick. If they’d led it towards the best way possible, then they have to do it the way I envisioned it. I surely don’t want to interfere with the director’s vision of things most of the time. I think all of the time, the effects fit right in to what the director wants, and that is to fool the people into thinking that what you’re seeing is really happening.

You mentioned “Grande Illusions.” If I’m not mistaken, in the first volume, you feature some of the storyboards for the 1990 “Night of the Living Dead” remake you directed. Working on that was a really painful experience for you since the producers made life hell for you and it was in the middle of your divorce. I’ve read you say you still have nightmares about directing that film. What gave you nightmares?

You have no idea. I still have nightmares where I’m on the set of “Night of the Living Dead.” The first two weeks were splendid. I was directing the hell out of that movie and everything that I wanted to do was getting done. But my divorce two weeks into it is what, mentally, just made me spiral into a zombie-like state. I had to direct this movie and then I also want to not lose my daughter and my money, you know? So when you’re directing something, all your concentration has to go towards the movie.

<span class="s1" The movie represents about 40% of what I intended to do, and those storyboards show you what I didn’t get to do. And I think it would have been a much better movie if I’d gotten to do it. It wasn’t … it was time that was the enemy. It was time. There just wasn’t enough time. I could’ve used another week on it and I understand it. You know, we had a budget of four-point-something million, and I think only two-point-something was used, so I don’t know where it went. This is just what I heard – I don’t know it as a fact. But when I heard it, I thought, “Shit! I could’ve used another week to make this movie what I wanted it to be!”

But you know what? I hear from the fans constantly how much they love the movie. “Better than the original,” even though the original is a classic. But film-wise, George did a terrific job on it. You know, we had a lot of years to perfect that. In fact, Barbara coming back in my “Night of the Living Dead” was my idea. George’s script was like the original film, it was an almost shot-by-shot reconstruction of the original movie, and I didn’t like that because I had just seen “Alien,” and here’s Sigourney Weaver as this female hero. I wanted Barbara to be a hero like that. So I suggested that to George at one of our meetings and he said, “But she’s dead!” I said, “Not really! You only see her grabbed and taken away. You never see her killed. Why can’t she come back and help them out?” So George wrote what you saw in my film. In the original, Barbara’s a braindead twit. In my version, she’s a hero. That might be why a lot of people like it more.

In a lot of interviews, I’ve read you say that Romero told you that … you basically thought you were just going to do the makeup effects, and he told you, “No, I have you in mind to direct.” Apart from the obvious reasons, why do you think he had you in mind for that project?

Well, I had directed three episodes of “Tales from the Darkside,” and of the 74 episodes of “Tales,” I think 10 are good. Mike Gornick directed a brilliant one, John Harrison directed a brilliant one. But two of the three that I directed had feature-length scripts come with them, to do feature-length movies on two of them. I keep hearing that they were the best episodes.

I showed them to George, and of course he saw them because he was the show’s producer. But he really, really loved them. So when he came to me and said, “We got financing for a remake of ‘Night of the Living Dead,’” I was thinking, “Oh, goody. I get to make more zombies like on ‘Dawn’ and ‘Day.’” And he said, “No, I want you to direct it.” So I drew up 600 storyboards and put them on the walls of my office.

In the meantime, there was a meeting with George and set people and whatever, and I would show them the storyboards and they were exactly what the movie was going to be. George saw that and he said, “This is brilliant stuff, but this is a six-week movie you have up on the wall, and we only have four weeks to shoot it.” So we were cutting stuff before we shot. I didn’t think that was fair because nobody knew what our shooting schedule was going to be, how many setups we could get accomplished in a day. To cut stuff before we shot it was, I thought, a little unfair.

You mentioned “Day of the Dead.” I read George Romeo say that you really came into your own on that film. That’s striking because that movie was so difficult, given how much had to be scaled back during production. I wonder if you could talk about working on that film.

That movie was scaled back before we even shot it. George’s original screenplay was thick as a phonebook and it was like “Raiders of the Lost Ark” with zombies. There were military camps and explosions! So he had to cut way back before we even started shooting. I remember going to meetings and discussing effects where somebody sets off this explosion and the cast is in the shot. We talked about these big 6 x 8 plexiglass screens to shield the actors from the explosions so that they wouldn’t get hurt. That’s about all I remember of prepping it. Then the new script came, and that was it.

The effects list I put together from the new script and that’s what I did. We improvised lot of other stuff; we’d come up with stuff and George just let us do it. Same on “Dawn of the Dead.” I’d say 60% of stuff on that was stuff we came up with and George just said, “Yeah, go ahead! Do it!” So that was great fun. George was like that. He was like an improviser and he let us improvise as special makeup effects artists.

I have to ask about another Romero film since I just programmed it for a movie series at the IFC Center: “Monkey Shines.” You still have the animatronic Robo-Chimp puppet for Ella the monkey in your attic. What was designing that animatronic creature a little easier after doing Fluffy for “Creepshow”?

Absolutely, yeah. I had never done an animatronic creature before “Creepshow.” I called Rob Bottin, who had just done “The Howling.” He’s a genius, and he spent a couple of hours on the phone telling me how to create Fluffy, which I did, and Fluffy worked. “Monkey Shines” was just making animatronic creatures, but on a very small scale. Robo-Chimp is only in the film in the scenes where you’re looking over the monkey’s shoulder at the actor, Jason Beghe. The monkey had to move left and right and up and down and his mouth would open.

We shot a test of me and Robo-Chimp, like I’m talking to him. And the producer came in and he saw it on the monitor and said, “Oh, you finally got those monkeys to do something!” He couldn’t tell, he thought it was a real monkey. And George Romero said that Robo-Chimp saved his ass on that movie because the real monkeys would make you really work for your money. They could figure out complex mathematical equations, but when you said “Action,” they’d do nothing.

So we shot a test before the movie, of me and the lead monkey, where I’m just playing with the monkey, but I’m acting like it’s attacking me. I was covered in monkey shit and it looked great. It never happened in the movie because Jason Beghe plays a paraplegic, so he can’t fight the monkey. When his character bites the monkey and thrashes it left and right, that’s a rubber monkey. When he throws the monkey and it lands under the table, that’s a dead cat we got from a company called Carolina Biological Supplies.

Oh my God.

And when the monkeys are lighting matches or wielding razorblades, that was a rubber monkey we built. So the real monkeys would sit there and you could agitate them; the trainers could agitate them and make them pound the table. But the fake monkeys were behind the table, doing this stuff while Beghe was in the shot.

It’s not a George Romeo project, but I haven’t ever seen you talk about your work on the Hong Kong film “Till Death Do We Scare.” What was working on that film like?

I went to Hong Kong with a VFX guy. They’d brought me with him to discuss the movie with the Chinese people in Kowloon. They wound up hiring me but not him, so I eventually met to Hong Kong with some of the props from “Creepshow,” like Raul, the silicon at the beginning of the movie. I brought him along with me and he’s in the film. But it was just me and Darryl Ferrucci, this 17-year-old kid, that went to Hong Kong. It was very frantic to shoot, because, in order to start a fog in a scene, they’d start a fire in a wastebasket, put a lid on it, and take the lid off when they wanted to fill the room with smoke. We worked with people who did Bruce Lee films, who worked with famous martial artists. Wellington Fong is the guy who hired me to come over and do the effects. It was great fun improvising those effects. It was me and Darryl, the same team that did all the stuff in “Creepshow.” We did all that stuff.

But going to Hong Kong, I lost a lot of weight, because I couldn’t eat there. The shrimp had big black eyeballs and long legs and the heads were … I couldn’t, I starved. Normally, I’d walk out of my hotel and turn right to go to the studio. One day, about a month and a half into production, I walked out of the hotel and turned left and there were all these American restaurants and delis. I was starving up until that point.

It’s really exciting to see that you’re directing again, especially with your segment for “The Theatre Bizarre,” and your upcoming web series. I wonder though, since 1990: has directing gotten easier for you?

It’s always been easy. It’s easy if you’re inspired. If I read a story and I see it, and visually I have all these ideas about how to show what the story wants to show. I do a lot of tracing on the monitor to make sure I can match somebody’s eyeballs on the screen for a scene we’re going to do ten days from now. I can line them up with what I’ve traced on the monitor. I’m really influenced by Dario Argento. He is a visual stylist. I’m blaring my own horn, but I think of myself as the same thing.

I don’t know if you saw a short film I did called “House Call.” It’s part of “George Romero Presents” … I forget now [Editor’s note: “Chill Factor”]. They bought that short from me, and put it in a collection of short films. That’s a prime example of what I’m talking about.

I have to be visually inspired. And then the whole thing is shot on paper. It’s like Hitchcock to me. He created the whole film on paper, and to him it was over and done at that point … but that’s what makes it easy. Directors are visually inspired, you have a shot list, and I do the same thing. The movie’s over when I create it on paper, but now I have to go out and shoot those shots. If you have a great crew and everyone is on your side, you can create those pieces exactly the way you created them on paper. That’s the fun of it.

I hope this doesn’t sound too creepy, but I’m a big fan of your Instagram and I wonder if we’ll ever see that great “Knightriders” costume on your Instagram.

Which one?

The leather one with the bike helmet.

The bikini?

There’s that too! [laughs] I meant the armor.

I did post that. I found the armor. I’m posing with it and I put the chest piece on and made a big deal out of it still fitting after all these years. It’s part of my … maybe it’s not on Instagram, maybe I did it on Facebook. I’ll have to go find that picture and put it on there.

Definitely. But let’s talk about the bikini. Arrow played up that photo you did in the bikini for the Blu-ray “Knightriders,” that wonderful shot of you flanked by two women as you’re lying on that divan. I thought about that photo after Burt Reynolds passed, that nude photo of him …

It’s very similar, yeah.

Is there a story behind that “Knightriders” photo?

If there is one, only George Romeo would tell it. All I know is they put the costume on me and said “lay down here.” One of the girls was somebody we got out of an elevator. She was just an actress who wanted to be in the movie! They dressed her up and she’s one of the girls who posed with us!

I am such a fan of your Instagram account, especially the videos where you’re hanging out and terrorizing your grandson. How old is he and what kind of horror films does he like?

Well, he’s three and he doesn’t watch horror movies. He watches “Paw Patrol.” But every now and then, I come in with an inflated gorilla suit and surprise him, just so he’ll run up and cower in my arms. Or we’ll have a gorilla/Godzilla fight. Or you’ll see him in the backyard with the Creature from the Black Lagoon, or an alligator behind him. I believe in starting them young, so he’ll be quite the horror fan!