Takashi Miike is the black, beating heart of world cinema. The man whose presence on festival circuits instills equal parts fear and wonder, the man you have to beware or watch. Miike’s rakish presence is perhaps best summed up by the title of his 2001 Yakuza movie, “Agitator.” Love or hate what he does, to reckon with it is to have your taste tested and your buttons pushed. Miike’s been an unyielding presence in film culture ever since he left his mentorship with the great Japanese director Shohei Imamura (from whom he clearly inherited a gift for finding laughter in the profane and a yen for codifying and classifying the inner workings of society’s underbelly) he’s been lifting rocks and watching as the insects beneath them flee for their lives from the piercing gaze of his camera eye. When limbs are hacked off, sex is turned to punishment, mores violated, and people destroyed, he stares unblinking at the gory remains.

But something happened about 15 years ago—Miike, the director of the fluid-selling “Ichi the Killer,” the legendarily nerve-shredding “Audition,” the hideously depraved “Visitor Q” and “Imprint,” started to show his softer side. 2006’s “Big Bang Love: Juvenile A” showed a tentative love story set in a dystopian prison; his movie “Ninja Kids” is exactly what it sounds like, and was appropriate for its intended audience; “Ace Attorney” was a genuine crowd pleaser; 2015’s “The Lion Standing In The Wind“ is a medical drama with the graceful restraint of a Merchant Ivory film; and 2012’s “For Love’s Sake” was a gangster musical with heart to spare. In short, Miike complicated his legacy and the easy way critics could reliably write about him. He was no aging enfant terrible hanging churlishly to a reputation for shock and awe. He was an artist with desires that spread all over the generic landscape. He could and would do anything that pleased him.

His latest is the deeply affecting “First Love,” about a boxer with a death sentence who decides to get mixed up in a beautiful girl’s troubles with the drug trade. With its long-night setting, its cast of delectably sadistic Miike types (including a one-armed assassin who carries a shotgun, and the ghost of a dead pervert who won’t stop dancing), and its use of duration to bring characters together, it’s classic Miike, even if the younger Miike would certainly have been crueler. It is a joy to watch, and as someone who’s been watching—awe-struck—everything Miike’s done since discovering him in high school, it was perhaps an even greater joy to sit down with a man I’ve mythologized for decades.

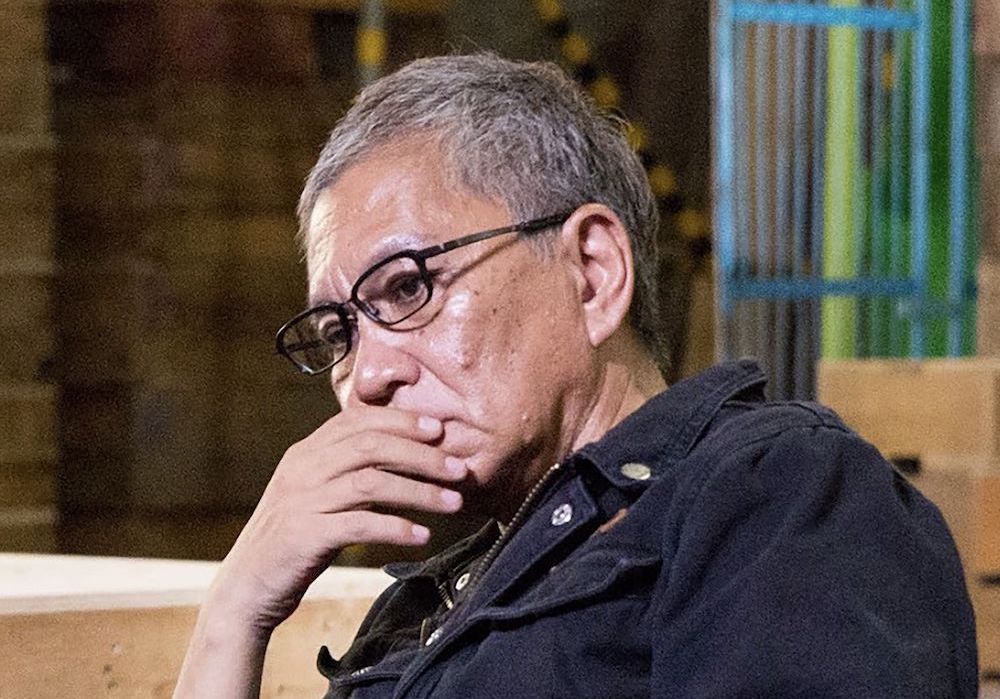

Miike is humble, shaking my hand timidly, and nodding frequently as his translator reads his answers in English. He’s clearly just as nervous about how I’ll receive them as I am about how he’ll respond to my questions. There’s a telling and lovely contradiction that won’t emerge until the interview is over that leaves me with confidence that I was right to love the man’s work. The man himself is lovable, even as, or perhaps because, he’s taken such joy killing people on screen all these years.

I wanted to talk about your cinephilia, because it’s something I’ve kind of made assumptions about over the years just based on little hints here and there, despite the fact that your movies don’t really behave like anyone else’s. I watched “First Love” and saw a little of maybe Kurosawa’s “Stray Dog,” through the cop who loses his gun and badge, maybe a little of classic boxing dramas like “The Set-Up” and “Night and the City.” Are your inspirations as clear as they sometimes seem?

My influences happen at more of a subconscious level, I don’t dig too deep into that or analyze it myself. I may say, “That scene in that movie would be perfect for this thing.” I’ll talk to my staff and say, “Oh you have to check out this film, it had this one scene that was really great!” In that sense I’m very straight forward about what my influences are. But more than being influenced by film in a tangible way that filters into my own work, I’m more influenced by things that happen in my daily life. The sunglasses that you’re wearing, somehow those sunglasses lodge in my subconscious and end up influencing me and they’ll end up in my next film and I won’t remember where they came from.

You’ve been adapting a ton of manga lately. Is there something about the form that especially speaks to you?

My generation was a special generation. I was born in 1960 and in my childhood we were all big manga consumers that was the culture. We were brought up in manga. Manga evolved around what was being made to cater to kids. All children at that time read ridiculously thick manga books every week. A lot of kids that wanted to be their dream to be a manga artist. That was the most popular thing, after being an astronaut, kids all wanted to grow up to be a manga artist. There was this unconditional respect that was infused in us for the genre. More than my films being influenced by manga I was indelibly impressed by Manga, and that definitely comes out in the films.

This film feels maybe more personal than a lot of your other recent work; it seems to hark back stylistically to films like “Ichi the Killer” and “Yakuza: Like A Dragon,” in the treatment of Yakuza, which you’ve shied away from a little.

There’s a little of that for sure. In films like “Ichi the Killer” you can say that these are real Yakuza but they’re also a fantasy. They’re film Yakuza, they’re not real. The traditional Yakuza are not considered suitable or even desirable by filmmakers or filmgoers. And that’s kind of sad because it’s a rejection of real people that existed in my generation. A lot of them have been caught by police and thrown in jail, so the true Yakuza who have their own unique values are just gone. So there’s a little bit of looking back, contemplatively, to the men I used to see in my generation.

Have you ever seen a work of art that captures the essence of the traditional Yakuza as you remember it?

Yes, absolutely there are several Yakuza films made right before I was born in 1960 that have a more erotic Yakuza feel. Ken Takakura [star of Yakuza films like Shigehiro Ozawa’s “Experience of Two Dispatched on a Trip of Hell,” one of the first Yakuza films to show off upper body tattoos in the Japanese cinema and later Imamura’s “Black Rain”] or Kōji Tsuruta [star of Yakuza films like Kihachi Okamoto’s “The Big Boss” or Kajirô Yamamoto’s “A Man Among Men”], those were real old school Yakuza that had a role in society. They weren’t originally a criminal organization. They became one later in an effort to survive and keep the organization alive. Originally they’d help weaker and more vulnerable members of society and actually help and compliment the authorities. Those kinds of Yakuza are gone from the current Yakuza organizations left, the vestiges of what they used to be. The real Yakuza are also completely gone from film.

Can you talk about the way you approach a scene? I’ve been watching your movies since I was about 14 and it still feels like you’re finding new ways to do simple things: filming conversations, for instance. There are several conversations covered in a way that feels experimental in “First Love,” can you talk to me about the way you begin to think about shooting a scene?

I feel like I find hints in the script, and when I’m making something I pay a lot of attention to the actors. If you have a dialogue between A and B, it will have a different flavor than when B talks to C. Every actor wants to stand out, they want to make the most of their role, but at the same time they’re feeling stress trying to fit themselves into what I’ve written. I’ll kind of take advantage of that, use that stress in conjunction with what’s written and find an interesting way to play people off of each other. That’s very important to find ways to focus on the characters and have the actors to play off each other, make the script feel more fresh and alive.

Has the response to the way you film violence been the same all over the world? Do you find yourself responding to the way your movies are talked about?

When I’m watching one of my movies in a festival with fans who are just into it and they love it? I end up feeling like my film is more interesting, it becomes more fun to watch and I get a special energy that feeds back into my process. I don’t want to make the same film over and over again. Once is enough so I’m trying to strike a balance there. At the same time the way I see violence is a little peculiar. What I consider to be particularly violent is a Hollywood film that has a scene where, to show off how amazingly buff and manly the superhero star is, everyone else around him has to die. Killing off the new actors, actors in smaller parts, extras, they all have to die so they can show how strong the lead character is. That is really violent to me, because the violence is based on, “If you’re a star, you’ll live, and if you’re not you’re expendable.” There’s a part of me that can only stomach a certain level of violence, maybe my threshold is lukewarm?

When “Blade of the Immortal” came out a few years ago, there was talk about it being your 100th movie. Was that cause for reflection on your career? I also hope that all the talk of retiring and being too old in “First Love” isn’t autobiographical.

I hadn’t been counting my own movies [laughs], someone at a festival said that. This is around a hundred? I thought, “A hundred? That’s horrible! Have I made anything good!? So far?” So then I thought I need to have a comeback, because I thought maybe I hadn’t done anything good yet. At the same time though I didn’t want to change my filmmaking philosophy or style, I wanted to keep going with the same M.O. as I previously had. At the same time I would like to make films that—violent or not—I can produce and depict it in a way that I like it and the audience also enjoys themselves.

Just before his translator was due to give me this last answer the sweet man knocked over his tea, a sickly green Matcha latte. Miike and I grabbed some napkins off the table to try to clean it up and his translator asked Myranda, our gracious host at the PR firm where the interview transpired, for more to clean up the spill. Miike stopped me from cleaning up and sat me back down in my chair so he could clean the rest of the stain up himself. The whole time he was listening to the translator give his answer, he was laughing about something and I was looking at him, dying to know what he was thinking. Finally the question ended and Miike looked at me and then pointed at the green stain and shouted with unmatched glee, “exorcistu!”

Suddenly, the entirety of Miike’s career shot into focus like an optometrist had changed settings. This guy, almost 60, still took such joy in being able to make a nerdy joke about a movie he liked, and that furthermore he knew I’d get because I was just as big a dork and a fan of films as he was. It was a beautiful harmonious moment, from a guy whose work I’d been studying like the pages of a holy book for more than half my life. Anyone like that is never gonna stop; they’ll go until they drop dead on set. Here’s hoping it’s at age 120, because Miike’s voice is too precious a gift to go without.