Trailblazing filmmaker Sally Potter began experimenting with moving images after her uncle gave her a 8mm camera when she was 14 years old. This passion continued with the experimental films she made after joining the London Film-Makers’ Co-op in the late ’60s. But it was her fiercely feminist debut film “The Gold Diggers,” starring Julie Christie and made with an all-female crew, that not only introduced Potter to larger audiences, but also announced a new era in British filmmaking. In her decades-long career since that auspicious debut, Potter has pushed the creative limits of the medium many times over, never afraid to try something bold, risky, or new.

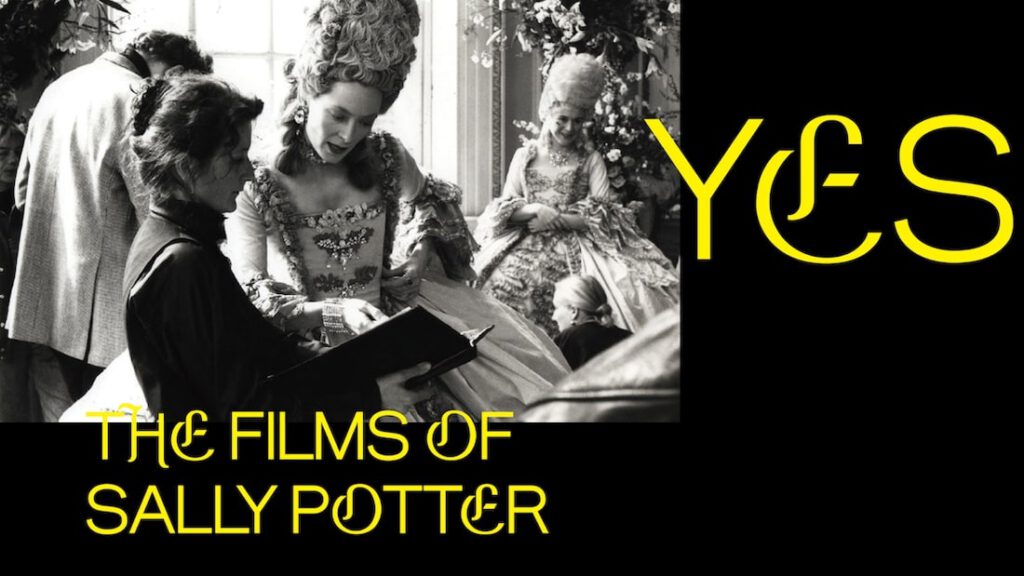

Opening this weekend at the Metrograph in New York City, Yes: The Films of Sally Potter offers audiences a rare opportunity to engage with the totality of her innovative body of work. Included in the retrospective are seven of her feature films, from her groundbreaking debut to a new 4K restoration of her breakthrough Oscar-nominated film “Orlando” starring Tilda Swinton, but also more hard-to-find films like “The Tango Lesson,” “Rage,” and “Yes.” Along with her feature films, the theater will be screening her early shorts in conjunction with her latest short film “Look At Me,” starring Javier Bardem and Chris Rock.

Although originally conceived as part of her most recent feature film “The Roads Not Taken,” her latest short “Look At Me” features Bardem as a volatile rock n’ roll drummer in a battle of wills with the frustrated director of a fundraising gala (Rock). As the short progresses, the true nature of their relationship is slowly revealed. Making its North American debut after its world premiere at the Venice Film Festival earlier this year, the short is as politically provocative and emotionally impactful as anything in her filmography.

Ahead of the retrospective’s opening at the Metrograph this weekend, RogerEbert.com spoke to Potter over Zoom about her latest short film, the themes found in her filmography, and the importance of discipline.

Your new short film “Look At Me” is about to have its North American premiere. It was part of your feature film “The Roads Not Taken,” which was a very personal film for you. I’d love to hear sort of when in the editing process you realized this didn’t fit into that film and how you decided to return back to your origins in short filmmaking?

I actually had a feeling even while I was shooting it, even while I was writing it. “The Roads Not Taken” is about parallel roads, literally, the roads we don’t take in life that we sometimes look back at and say, oh my god, if I’d stayed in that relationship, what would my life be now? Or if I’d emigrated at that point in my life, what would my life look like now? That was the state of mind that Leo (Javier Bardem) is in. He’s going down all these neural pathways due to his neurological condition that allow him in a way to visit his parallel possible existences. This was going to be one such one path. But what I also realized very quickly was that this story was completely a story apart. The others were all interlinked. They all made kind of sense in terms of the choices that somebody would make.

But this was like, just a totally different story. I don’t know why I didn’t fully sense that while I was writing it or while I was shooting it. I think it’s partly because I was really enjoying it as a story in its own right, and the characters in it, and what it was doing. So I totally went with the flow and made it, but as soon as I got into the editing room, I realized, Oh my god, I’ve made a film inside another, like a Russian doll. It’s like it’s sitting inside and actually doesn’t belong there. So with searing heartbreak, I removed it and put it on one side thinking, I can’t cut out this sequence that I love so much, but I knew I absolutely had to. I thought, Okay, one day, I don’t know how soon it’s going to be, but I will turn this into a separate film. So finally, I did, and that’s the way it feels; it feels like it really is its own film. It may have been shot on the back of the other one, but it’s absolutely its own story. It was fascinating to me to go back into the rushes and remake it as a dedicated short, not having made a short for decades. It’s such an interesting form. It really has its own disciplines. It’s not like practicing for the real thing, a feature, which is how people often think of shorts. It’s like short stories with its own disciplines and rhythms. It was fascinating to make and really enjoyable.

In a way do you feel that it was similar to Leo in the feature film? He’s looking back at choices he made when he was younger, and where he would be when he was older if he had made those choices. With filmmaking, you started out doing shorts, so I’m curious if it felt similar, just in terms of revisiting that sort of creativity you had when you were younger and making shorts?

It felt like something new. It didn’t feel like going backwards at all. It felt like an exploration of the short form, which is in fact, completely of this moment. People’s sense of duration right now, has radically shifted because of social media and streaming and the way that people absorb the moving image. So whilst there’s still absolutely a place for the classic feature length experience, a lot of people absorb shorter forms at speed. I don’t think that’s at all a bad thing. Some people really diss them a lot, and say nobody’s got any attention span anymore. I say, well, no, people have got a lot faster. They just read images really quickly. So I approached it like that. As something absolutely of this moment. New. New for me too, which is exciting.

Going back a bit to “Orlando” and this restoration …

Thirty years!

How do you feel about it being the film that most people know you for? It seems, myself included, people come to “Orlando” first and then get to the rest? What do you think draws people in?

I think, first of all, the central idea is sort of eternal, timeless, and universal. In other words, everybody, if they dare to think about the fact that one day they won’t be here, has to contemplate the notion of mortality and therefore of immortality, and where we are. What is this experience of living longer than a human lifespan? What would that be like and so on? That’s an absolutely transcendent kind of concept. Then what Virginia Woolf did is in her book, she married that idea, that feeling, that exploration, with the idea of what would it be like to live life as a man and then live life as a woman? What experiences would you have if you’re the same person, no difference at all, just a different sex and subsequent to that? That’s also revolutionary. And, of course, now completely timely.

So it’s as if each epoch of the existence of the book first, and then of the film over these last thirty year, it’s always up to date. Because I decided to come at the subject matter in a very modernist way. Big words, not that kind of reverent heritage bonnet picture. But really a kind of go for it approach. I think that makes it continue. It seems that it makes it continue to feel fresh and light. Humorously dealing with these quite big transcendent stuff. That is my explanation anyway. Then, of course, the way it looks. Sandy Powell’s amazing costumes. Tilda Swinton’s incredible performance. Aleksey Rodionov’s amazing camerawork. And I have to say my rather good adaptation.

It’s definitely a film I have returned to often. There’s so many layers to it. In preparing for this interview, I watched a few films of yours that I hadn’t seen before. One was “The Tango Lesson,” which floored me. I loved that film so deeply. In a retrospective like this, there’s so many of your films that are probably going to find new audiences. Are there any films in your filmography that you’re particularly excited for audiences to either discover or rediscover?

The two that spring to mind, aside from“The Tango Lesson,” which you’ve mentioned already—but which was a very intriguing thing to do immediately after “Orlando” in a very so risky, in a completely different way—are a film called “Rage,” which was the first film, I’m told, ever to be designed to be watched on mobile phones. At the time it was considered outrageous. There were headlines in the paper, “Sally Potter Is Trying To Kill Cinema.” But I was just embracing the new. So that would be interesting for you to see, perhaps, on a big screen. The other one is “Yes.” Which again, was a different kind of risk, because of it being all written in verse and the subject at the time was very difficult. It is about a love affair between a Middle Eastern man and an American woman. So trying to turn what was the beginning of incredible hostilities and deaths, awfulness, and ghastliness, and to make them go the opposite way, and have curiosity and mutual understanding. So I’m differently proud of both of those. They never had the same audience numbers as “Orlando.” But I think they may be interesting for people to see them now.

Do you think with this restoration of “Orlando” and with this retrospective that there is a possibility of having a home video release for some of these films that are harder to find? I know “The Tango Lesson” had a DVD release, but it’s hard to find now.

Ask Sony Pictures Classics [laughs]. But yeah, I’d love to. I mean, all of the films do crop up now and then. Somebody will say, “Oh, I saw ‘The Tango Lesson’ on TV last night at midnight” or something. I’m not usually up to date. I think the wonderful thing, actually, about the whole sort of digital universe is that it is possible to remaster some of these original films, especially those that were shot on film, and introduce them to a new audience, a new generation. I just had that experience at the Telluride Film Festival with “Orlando,” with the first showing of the remastered version there. The audience was mostly young, a lot of them students, and they’d never seen it before. They were very open mouthed. I did a student symposium afterwards and realized, every day, a film can reach a whole new audience. It’s as if it could have been made yesterday. So it’s a wonderful potential. I’d absolutely love it if these films could be released.

I will harass every single distributor I know because I want more people to see “The Tango Lesson” in particular. You spoke of shooting on film earlier. Several of your features and shorts are shot in black and white. In particular, I remember seeing “The Party” in theaters, and thinking the black and white is so bold today. What do you love about working in black and white?

I think first of all, I’m sure that as I was growing up, a lot of my favorite films were in black and white. So I have a great feeling for it in terms of memory, because most of the great classics were black and white. But also, I think the great beauty of working with black and white is what you get from a purely visual point of view. It does things to your brain. You get true black and true white contrast, which you don’t have in color. So with that kind of light and dark, your retina is literally kind of opening and closing in a particular way as your eye scans the image. I think that creates a kind of dance within the brain. I’m talking fake neurological here. This is not science, but it’s my sense of how you absorb black and white. The eye swipes the image in that way. Also, it simplifies things, like the chaos of color. You get shapes and you get a feeling of a three-dimensional world drawn like a charcoal drawing, that your mind then reinterprets in color. So in a very peculiar way black and white experientially is more colorful than color. Because you are coloring it in, in some sense. There’s a kind of freedom of that in the imagination. It stimulates the imagination in some way that I love. I love working with black and white.

I’m a classic film, silent film sort of junkie, so seeing good uses of modern black and white always thrills me. I want to talk about some of the themes I found in your work for me in particular. I love the way many of your films discuss the difficulty women have in fulfillment, whether it’s creative fulfillment, or familial fulfillment. That kind of push and pull, like they have a family but they aren’t creatively fulfilled. I thought “Ginger & Rosa” was a really interesting one, where the teenagers look derisively at their mothers, but they don’t really understand the struggle their mothers went through to even just have the lives they have. And I’d love to hear your thoughts on if that is a theme you find in your films, and what you find is interesting in looking at the various generations of women.

It’s certainly in “Ginger & Rosa.” I wasn’t aware of it as a theme in my other ones, but it may be there. If you’ve experienced it, then it must be there. I think that in “Ginger & Rosa” I particularly wanted to explore that generation of women. I grew up in that period. I was like 11 I think during the Cuban Missile Crisis. I’m a little bit younger than the generation I was portraying, but the generation of mothers of these young women were the post-war generation. In the ’50s, women were pushed back into the home and domesticity was being romanticized again, as men came back from war and wanted to take their jobs back. So the freedoms that women had paradoxically had during the Second World War, to drive ambulances, work in factories, to explore professional lives, do all kinds of things, despite the incredible ghastly, horrible difficulties and pain of war.

Nevertheless, there were certain freedoms that happened to women, and those freedoms were taken away again in the ’50s. So you have a whole generation of women who tried to, in a way, accept and enjoy domesticity as their lot, the arena of the home. But this didn’t suit all women. So there were a lot of frustrated women, I think, who felt that they had given everything to their children or to their families, but never found themselves in some sense. My own mother came into that category. So I think I wanted to give a kind of compassionate portrait of both the mother in that situation, but also of the feelings of the daughters who look at their mothers and go, no I don’t want to be like you. And of course, they’re cruel. Teenagers are cruel. But it comes from looking at their mothers and suffering with them in some sense, and then also resenting that. Which other films did you see that same theme?

I felt a little bit of it in “The Party.” The women in that film are looking back at their lives and their choices and where they are and assessing their situations. Patricia Clarkson’s character, she feels very, maybe not unfulfilled, but she definitely feels like she’s at a point in her life where she’s not sure she’s done the right thing and made the right choices.

That’s interesting, because I saw Patricia Clarkson as somebody, well her character has a sharp tongue. She has all the best one liners in the script, and she claims the right to be irritable, and, and so on. I didn’t perceive her as unfulfilled. I perceived her as somebody who had made the choices. The choices of being a single woman and non-mother. There’s certainly the contrast between the mothers and the non-mothers. There’s Kristin Scott Thomas, the politician who chooses to have a life, a career, a success, and then the portrayal comes from behind, in private. Now, we’ve seen that, very importantly, with several biggest public female figures this has happened. So I was exploring that. But the choices that we all make are interesting and the choices that sometimes that we are not able to make, or the choices that are not yet not available to us of all the different generations.

You also have this recurrent theme of men having difficulty dealing with their own emotions and their own feelings and sort of wreaking havoc on people’s lives. I’m thinking of Alessandro Nivola’s character in “Ginger & Rosa.” But also with Javier Bardem in “The Roads Not Taken,” who in the various lives he’s thinking about there’s emotional choices that help him, but take things away from other people. I think it’s really interesting the way that those later films center on men a little more. Not necessarily center, but there’s definitely a lot of exploration of men and their emotions in some of your later films.

Absolutely. In “Yes,” there’s equal central parts between Simon Abkarian, who plays the Middle East man, and Joan Allen, the woman, and there is really a compassionate look at each. And I think it’s, well, we know it’s true that male conditioning, perhaps not so much now, but certainly in many countries in the world now, and in the West certainly in the previous decades, young boys are not given the same space to truly feel what they feel and express what they feel without being mocked for it. So that creates real distortions in the psyche and great, great problems. And women are given more permission to access what they feel. Even if those feelings are hard and difficult ones that they don’t want to have. We are, generally speaking, more able to access them.

That’s shifted to some degree, which is good. But I indeed wanted to explore what happens when you remove people’s normal and natural kind of humanity and vulnerability, and try and pretend that that isn’t there? What starts to get distorted and what starts to go wrong with the psyche? And that’s not only a male problem, but it’s, as a generalization, boys don’t cry and girls are encouraged to be a bit fearful. Don’t do that, you might fall. That kind of thing. So women get this kind of fear thing happening that is very limiting, the feeling of limits, and boys get a, I’ve got to be tough and not have feelings and therefore forget how to be empathetic and to understand how their actions affect other people.

I thought that was particularly well done in “The Roads Not Taken.” But then when it comes full circle, that final moment with Elle Fanning is really lovely. Where she realizes he is thinking about her this whole time. I thought that was really impactful. Which brings us back to the shot. It’s a very political short, and obviously, your films have always been very political. “The Gold Diggers,” when you think about the era when that film was released, is incredibly political. What are your thoughts on whether art in general could ever not be political, whether it’s subtextually or surface level clearly political, do you think that’s possible to separate the two?

No, because I think what tends to happen is that the word political gets attached to something which is oppositional, which is questioning the status quo and the status quo is supposedly not political. This is not true. Everything, when you start to look at it, you can analyze it in political terms, or in terms of oppression or liberation, or structural or institutional sexism, or racism. All of those things are everywhere. Literally everywhere, and so you can’t ignore them.

But it’s always been a problem that the status quo is considered neutral, somehow, and this other thing is like, red flashing lights, isn’t it?

I think for me, it’s very joyful to want to address all those things. It’s a kind of exuberant feeling of reality. It’s like restoring people’s experience to them, of this is how it feels and I can reflect it back to you; yes, it is like this! And so that’s part of the feeling of what cinema can do. When watching a film, the feeling that I’ve had anyway when I’ve watched some of my favorite films, suddenly everything sort of comes into focus. It literally comes into kind of a focus, experientially. Literature, of course, can do that too. A wonderful book where you feel you’ve woken up to a whole level of reality through reading it. Politics as a word is rather general, right? But I love the feeling of, let’s dig down and look at what’s behind the surface and how all these dynamics work.

I am definitely on the side of everything is political, because life is political. But the word political gets misused. I think people think of it as one single thing, and it’s literally everything. I read that you like to work parallel on several projects at once. You’ve made so many films in the last ten year it feels like you’re always working. Are you working on several things now, and if so could you share about anything that might be coming down the pike?

Yes, I am. I always have a queue of stuff on my desk or in my head or in you know. I have a script that’s ready to go, but I’m always cautious about talking too much about stuff before it’s made because they often change. I’ve occasionally announced a film with a title and everything and then a few years later it comes out and it’s not completely different, but it’s different.

Like how “Rage” was a bit in “The Tango Lesson,” but then when it came out over 10 years later, it was slightly different.

Exactly. Sometimes I just plant the seed of a thing. But I can say the new one I’m working on is called “Alma.” That’s the next film I’ll probably be shooting. I wrote it after I made “The Party,” when I discovered that I loved writing stuff that made people laugh. I mean, that’s always been a thing. People laughed during “Orlando” and I was just delighted about that. But when I was at the premiere of “The Party” at the Berlin Film Festival, which was a huge cinema of I think 2,000 or 3,000 people, and the ground was shaking with laughter in the cinema, people were laughing so much. And I thought, Oh, this is wonderful. This is healing. It was great. So it’s a rather bleak comedy. So let’s see if I do that now. I’ve also been working on a lot of music stuff. I write music. I wrote the scores for my films, and I’ve been dedicating myself to some songwriting, too. So we’ll see what happens with that. But film wise, I hope that will be the next one that I shoot.

When you’re working on something creatively, do you ever feel the need to recharge? And if so, like, how do you recharge that creative spark?

I don’t ever have a problem with recharging, actually. I mean, what I always think is creativity is not really so much about creativity. I don’t use that word much at all. I don’t use it. What I do talk about is habit and discipline, which maybe sounds a bit more boring. But I basically think that—and I learned this as a dancer—you get better by doing something every day, whatever you feel like. It’s not about feeling inspired. It’s not about feeling creative. That’s a bonus, it happens occasionally. But mostly it’s about getting down to it. The more you work every day, every day, every day, every day more and more and more, you get better at what you do. I love working so much that there’s no pain involved in that. If I break the habit, if I stop for a little while for a few days, it’s always harder to get back on the horse again. But as long as I’m in that sort of rhythm of productivity, I just love to work. So I work as many hours as I possibly can every day,

I find that incredibly inspiring. I feel the same way. If I take too much time off, which I do way too often, then it’s harder to get back on whatever project I had been working on.

It’s about developing a good habit, isn’t it?

Yeah, it really is.

I talk with students about that. They often want to know, how do you find your inspiration? You know, and I say, mainly it’s not about inspiration. It’s about forming good habits and keeping going with that. It’s so simple.

Most of my body of work is in celebrating the films directed by women and in highlighting women whose history has not been as mainstream, and I would love to know if there are any women either from the breadth of cinema or who are working today that perhaps you find inspiring?

This is such a tricky area because I grew up in a time where I couldn’t find any. I was alone as a female filmmaker. That has changed so much and I think for young women filmmakers now they can’t even imagine what that was like, to be so to speak first through the gate. I mean, in the UK anyway, when I made “The Gold Diggers” I don’t think any woman had made a film since the war.

Muriel Box.

Yes, since Muriel Box. But nevertheless, I remember when I found Dorothy Arzner’s film “Dance, Girl, Dance” and I thought that was amazing. Of course Agnès Varda’s “Cléo from 5 to 7,” which was so underestimated. She was doing what Godard and Truffaut got all the credit for, inventing the New Wave, when she was the first in many ways. There was also Chantal Akerman, when she started doing her work. So there were these kind of beacons here and there. When there were not so many female filmmakers. I found my inspiration from women working in different fields.

I consider Billie Holiday my teacher. I would sit and listen to her LPs, as they were called, again and again and again and again. She was my master. The expression, the range, the subtlety, the phrasing, the feeling of humanity and so on in her voice. One can find one’s sources of solace and inspiration, historically, in different media and of course writers, like Virginia Woolf and Jane Austen. There are so many writers who managed to forge a path in their own ways. I don’t think one should get to, in a way, distressed about female absence from any medium, but rather look at where we always have been, and get inspiration and solace from that.

“Yes: The Films of Sally Potter” begins at the Metrograph on October 7th.