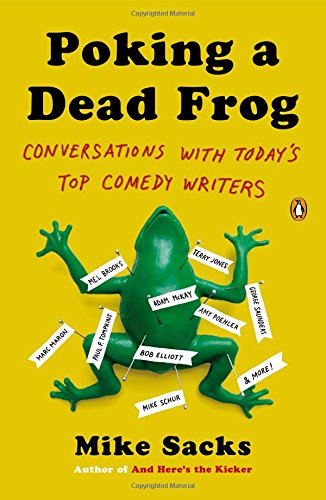

”I am no humor expert,” Mike Sacks states in

the introduction to his new book, “Poking a Dead Frog: Conversations with

Today’s Top Comedy Writers.” But with this sequel to his 2009 book, “And Here’s

the Kicker” (recently re-released in what he calls an expanded “director’s cut”

edition with 200 extra pages), Sacks, a Vanity Fair staff writer, has

established himself as an insightful observer of the elusive comedic process.

“Dead Frog” (not to be confused

with Monty Python’s “Dead Parrot”) features interviews, “ultraspecific comedic

knowledge” and “pure hardcore advice” from a stellar array of legendary,

veteran and emerging comedic artists, including standups and performers (Patton

Oswalt and Amy Poehler), cartoonists (Daniel Clowes

and Roz Chast), and writers for radio (Bob Elliott of Bob and Ray legend), sitcoms

(Glen Charles, “Cheers”), late night talk shows (Todd Levin, “Conan”) print and

online (Henry Beard, “The National Lampoon” and Carol Kolb, “The Onion”) and

movies (Diablo Cody, “Juno”). And Mel Brooks!

The book (which you can buy here) takes its

title from E.B. White’s oft-quoted

observation in The New Yorker: “Humor can be dissected, as a frog can, but the

thing dies in the process and the innards are discouraging to any but the pure

scientific mind.” But Sacks’ deft poking unearths for comedy fans, nerds and

obsessives some precious treasures, such as Bill Hader’s list of 200 movies

essential for every comedy writer to see and Paul Feig’s intimately observed

show “bible” for the late, lamented, “Freaks and Geeks.”

Acknowledging

this site’s founder, Sacks began our conversation with an

appreciation of Roger.

MIKE

SACKS: He meant a lot to me. I thought he was an amazing writer and an amazing

person.

What was your exposure to him?

I grew

up in the D.C. area pre-Internet and pre-cable. There were a few great

reviewers for The Washington Post, but as far as movies I would have never

heard about otherwise, it was Roger Ebert. I just found him to be a great

writer, especially about the passage of time. His humanity, too, always came

through. He was my first link to a world (of movies) that I didn’t really know

about, movies that wouldn’t play on the big screens where I lived.

Going into “Poking a Dead Frog,”

how did you want to expand the conversation about writing comedy from the first

book?

With

‘And Here’s the Kicker,’ I wanted the interviews to be longer, but they were

cut back by the publisher With this new one I wanted to get into longer, Playboy-length interviews that would

have a nice arc—inspirations, experiences, advice. But the main purpose,

really, was to have another excuse to talk to my favorite comedy writers. I

wanted to focus on those who wouldn’t be here much longer, like Peg Lynch, 97,

as well as those who are emerging like Dan Guterman (‘The Colbert Report’).

“Kicker” was published in 2009.

How has the comedy landscape changed since then and how did that impact how you

approached this book?

That’s a

good point. When I pitched the first one, there were no books like this and

very few comedy sites. Marc Maron’s podcast (WTF) didn’t exist. The Onion’s A.V.

Club and a few other sites dealt with comedy. That was one of the problems with

the first book. It took a long time for

it to get published. It was rejected 25 times or so. Since then, things have exploded. There are

podcasts and websites. People seem to be making a career out of writing about

comedy. The New York Times has a comedy critic, Jason Zinoman.

Did the first book help you open

doors for the second?

I wish.

(laughs). No, in fact, it was more difficult. There is a lot more competition now. These top writers are being asked

much more frequently to be interviewed. With the first book, I would email

people like Larry Gelbart and others—the older ones who had AOL.com email

addresses—and they would get right back to me. With this one, it seemed like

there were more layers. I think it’s great, actually, that these people are

being asked to be on podcasts and to be interviewed for Splitsider, which is an

amazing website, or A.V. Club. But it wasn’t as easy as I thought it would be.

Analysis of why something is

funny can be deadly, but to your credit, the interviews are fascinating inside

looks at the process of creating comedy, which is much more illuminating.

Thanks,

but that goes for any occupation. Whether it’s a brain surgeon or an

electrician, every occupation has a process to it, a language and a lingo. “How

can one learn to be funny?” is an impossible question. What fascinates me is

(the writer’s) experience. How does one go from being a kid in Illinois, or

wherever, to becoming a professional writer of jokes? How does that happen? To

me, it’s a very mysterious process, but one that has always interested me.

I was fortunate to grow up in the

heyday of comedy albums, and watching comedians on “The Ed Sullivan Show” and

Johnny Carson’s “The Tonight Show.” What was your gateway into comedy?

It was Letterman and “Late Night,” and

especially Chris Elliott.

Mike Schur (“Parks and

Recreation”) remarks in your interview with him that reading Woody Allen was

like seeing in color for the first time. Was Letterman like that for you?

It was a

sensibility that was very approachable for a kid. The writing on that show was

so sharp and anti-everything we had not really enjoyed on TV variety shows.

Letterman cut through the BS. A lot of

the credit for that goes to (his former writer) Merrill Markoe. Her voice was

so strong. She really influenced an entire generation of comedy writers and

lovers.

Jerry Seinfeld has gotten flack

that his guests on “Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee” are not more diverse.

What was your process in seeking out your interview subjects?

It

wasn’t anything more than getting people whom I liked and, quite frankly, who

said yes. Beyond that, it was those who said yes and where the interview worked

out. A lot of interviews don’t. I interviewed 70 people and 45 made the final

cut. I think it helps, too, to be open

to everything, to have your feelers out to see what’s out there, whether it be

TV, movies, Twitter or graphic novels.

One of the biggest “gets” of this

book is Peg Lynch (creator of a Seinfeldian 1940s radio series, “Ethel and

Albert”). How did you find her?

That was

total luck. I would love to say that I knew about ‘Ethel and Albert’ where no

one else did, but what happened was I contacted an expert in radio humor and asked

if there were any radio comedy writers out there. He gave me a list of 15 who

were alive the last he checked five or 10 years ago. I went down the list, and

all of them were gone except for Peg Lynch who I tracked to a town in

Massachusetts. I called the town hall and they gave me her number. We proceeded

to talk for two hours at the first interview. It’s not like she was waiting for

someone to call necessarily, but I think she was perplexed as to why no one

hadn’t. She had not been interviewed in at least 50 to 60 years. She was one of

the few female comedy writers in the 1950s and ‘50s. She told me that over the

years, she has written more than 2,500 scripts. Her memory is incredible. And

the stories she told. It was like discovering gold. What was frustrating was

she kept saying, ‘This is nothing, you should hear the real story.’ I’d say,

‘Please tell me the real story.’

Your last book featured interviews

with Irving Brecher (who wrote for the Marx Brothers), George Carlin and Harold

Ramis, all of whom have since passed. While reading the new book, I couldn’t

help wish that you had been able to interview, say, Michael O’Donoghue

(co-founder of The National Lampoon”) before he died. What deceased comedy

writers do you wish you had gotten a chance to interview?

[O’Donoghue]

is one of them right there, and Doug Kenney (“Caddyshack”). Michael was real

slash and burn and Doug, it seemed to me, was a gentler spirit. And those two

working off each other [on “The National Lampoon”] was an amazing combination. I

would love to have talked with them.

What was your process like for

preparing for these interviews?

It was a

lot of work, up to 35 hours of research per interview. The problem was I didn’t

know how good (an interview) they would be, so I could do all that work and

then get on the phone and know instantly it was not going to work out. So that

was 25-35 hours down the drain.

One of the things I like most

about both books is learning about the writers’ influences and being introduced

to works that inspired them.

Usually

it starts with one figure and you go back and see what influenced them. I’m a huge Woody Allen fan and through him

you discover the Marx Brothers and S.J. Perelman. With Letterman it was Steve

Allen and Bob and Ray and all of those amazing people who influenced him. It

goes back and back and back. There is always someone to influence the next

generation.

A lot of

people turned me on to things I didn’t t know about. I hadn’t seen a good 80 or

so of the movies on Bill Hader’s list of the 200 movies every comedy writer

should see. It was just a good opportunity

to see what influenced someone who is that brilliant as a comedian and

performer. (The 1945 film noir) “Scarlet Street” is another good example. I had

never heard of it until Dan Clowes mentioned it. I learned a tremendous amount

form these people.

What is perhaps your biggest

takeaway from your interviews?

(Even at

their age) Mel Brooks and Peg Lynch are people who are never content with

resting on their laurels. They always want to achieve. That’s a tremendous

lesson for anyone. Mel Brooks gets up every morning and he goes to work. And as

writers that’s what you have to do. In the end, you just have to write. I would think someone like him would be satisfied

with what he’s accomplished but there’s an eagerness and hunger. He’s about to

go on Broadway to perform a one man show at 88 years old. What kind of

personality does that? It’s the same kind of personality that at 24 (drove him)

to get out of Brooklyn and achieve.

A recurring theme of these

interviews is that comedy is hard work

That’s

another valuable lesson. It doesn’t get easier. Someone who has written jokes

for 80 years still has questions whether a joke will work. Nothing (in comedy)

is guaranteed. If it’s hard for Mel Brooks, why shouldn’t it be hard for the

person who’s just starting out? There is no one answer in comedy. It’s not a

math equation. There’s always a sense of mystery.

You write very optimistically that

this is a golden age for comedy writing, but I wonder if this is more of a

golden age of opportunity?

I think

both, certainly compared to when I was in college and there were very few

outlets. With social media, someone writing jokes in their room in Maryland can

theoretically compete with, or have as many readers as New Yorker.com, That

didn’t exist before. The gates were being controlled by a certain type of executive

or whomever. One can circumvent that, which is pretty astonishing.

This is your second book of

interviews with comedy writers. Trilogy?

I don’t

know, I don’t think so.

Wait; In your interview with

(“Cabin Boy” director) Adam Resnick, he said he would wait for the third one to

talk to you about “The High Life” (his short-lived HBO series).

I think

it’s two and done, but I would like to write about ‘The High Life.’ (Adam) said

he was going to give me some bootleg VHS tapes. I’ve seen a few episodes, but I

would love to see them all.

One other thing: In your

interview with Henry Beard, he reflects on Ernie Kovacs and one of his

signature creations, the Nairobi Trio (gorilla masked musicians making like

wind-up toys to the tune of “Solfeggio”). He calls the bit “beyond bizarre” and

wonders, “Where did that idea come from?” In that spirit, I have to ask: You

include among your acknowledgements a reference to the 1979 teen rebellion

drama, “Over the Edge” (“To the upstanding citizens of the planned community of

New Granada—Tomorrow’s City… Today). Where did that idea come from?

God

bless you. That was in the first book and no one pointed it out. That’s one of

my favorite movies. It’s very underrated. That’s a case of a movie that’s not a

comedy, but it really influenced me. It just resonated. It was very ahead of its time in portraying

the reality of pre-fabricated communities and kids doing the best they could in

that environment. I loved the sign that opened that movie (referenced in the

acknowledgements). It was so yearning and so positive and what the reality became

was so awful.

And the photo that accompanies

the “About the Author” page. Isn’t that Jon Hamm?

He is

such a nice guy. He liked the first book. He posed for three or four hours on a

Saturday last year. For free. He just did it because he’s a fan of comedy.”