Kim Novak returned Wednesday to her hometown of Chicago to preside over a screening of the film many people believe is the best that either she or Alfred Hitchcock ever made. A restored version of “Vertigo” (1958) was shown in a rare 70 mm print at the Chicago Film Festival, and afterward Novak came onstage for a question-and-answer session that spanned her career.

In an interview earlier Wednesday, she recalled the advice of Columbia Studios czar Harry Cohn, before he loaned her to Universal to make the film for Hitchcock. ” ‘It’s not a good screenplay,’ he said. ‘But he’s a good director, and he may make something of it.’ “

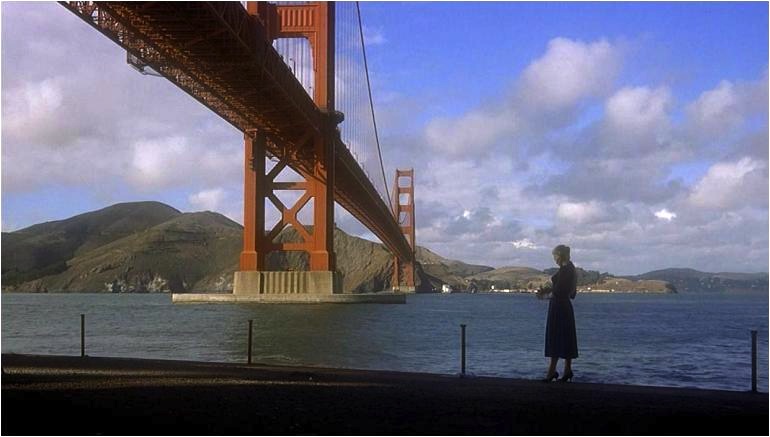

He did. He told the story of a phobic retired police detective (James Stewart) who falls in love with a woman he sees only at a distance. And then, apparently, he sees the woman die.

Little does he suspect that both the woman and her death are fictitious – part of an elaborate murder plot. But when he encounters someone who looks exactly like his fantasy-woman, he persuades her to play the role of the woman in his dreams.

What he doesn’t suspect, of course, is that the woman he meets, named Judy, is the same woman who portrayed “Madeleine,” the woman he dreams about.

Novak plays both roles. And there is a moment in the movie where, as Judy, she allows the Stewart character to make her over into “Madeleine.” She walks toward him, as he’s caught up in a frenzy of passion and gratified desire – and she feels a great sadness because she has come to love Stewart, and realizes he can’t even see her; he only sees the woman in his imagination.

“Of course, in a way, that was how Hollywood treated its women in those days,” Novak said. “I could really identify with Judy, being pushed and pulled this way and that, being told what dresses to wear, how to walk, how to behave. I think there was a little edge in my performance that I was trying to suggest that I would not allow myself to be pushed beyond a certain point – that I was there, I was me, I insisted on myself.”

Novak had a reunion in Chicago with James C. Katz, the famed film restorer, who with Robert Harris took the aging materials of the Hitchcock classic and turned them into a fresh new print. He told her something she didn’t know. She was paid only $750 a week to appear in “Vertigo” – but records uncovered by Katz indicated that Universal was paying Columbia $2,500 a week for her services.

“You mean Harry Cohn was pocketing the difference?” she said. “He screwed me every way he could . . . of course except for the one way that counts.”

I asked if the old Hollywood legend was true, that Frank Sinatra went to Cohn’s funeral “just to be sure the SOB was dead,” and she laughed and said it wouldn’t surprise her.

Novak was romantically linked in the 1950s with Sinatra and other Hollywood stars, but she talked of only one relationship, with Sammy Davis Jr., that ended when Cohn’s spies threatened Davis with bodily harm if he continued to see her.

“It wasn’t a romance so much as a friendship with a beautiful man,” she said. “He was so sweet and good, and something inside of me rebelled when I was told not to see him. I didn’t think it was anybody’s business. If he had been a bad man, a dangerous man, then the studio might have had reason – but simply because he was black?”

Working with Hitchcock was strange, she said, “because I don’t know if he ever liked me. I never sat down with him for dinner or tea or anything, except one cast dinner, and I was late to that. It wasn’t my fault, but I think he thought I had delayed to make a star entrance, and he held that against me. During the shooting, he never really told me what he was thinking.”

It has been said that “Vertigo” comes closest to revealing Hitchcock’s innermost obsessions, which had to do with controlling his actors, particularly women, and dictating every nuance of their behavior. By trying to do that with “Judy,” the James Stewart character finds he simply cannot find the dream he seeks.

“I don’t know how autobiographical the film was – or even if it was,” she said. “I know that Hitchcock gave me a lot of freedom in creating the character, but he was very exact in telling me exactly what to do. How to move, where to stand. I think you can see a little of me resisting that in some of the shots, kind of insisting on my own identity.”

Novak was born in Chicago in 1933, attended Farragut High School, was a beauty queen as a teenager and a Hollywood starlet before she was 20. Among her best-known roles were “Picnic” (1955), opposite William Holden; “The Man with the Golden Arm” (1956), opposite Sinatra; “Pal Joey” (1957), again with Sinatra, and “Bell, Book and Candle” (1957). The restored version of “Vertigo” starts a commercial run here today at the McClurg Court; a restored “Picnic” starts Monday at the Music Box.

While she’s back in Chicago, she said, there is one haunting fear she wants to exorcise.

“I have a recurring dream,” she said. “It’s late afternoon – rush hour. I’m in the Loop and I need to get home. I lived on the Far West Side. There are no cabs. There’s no way to get there. I start to walk home. It’s dark and dangerous. That’s a bad dream I’ve had for years. So while I’m here, I’m going to retrace that journey. Maybe put that nightmare to rest.”