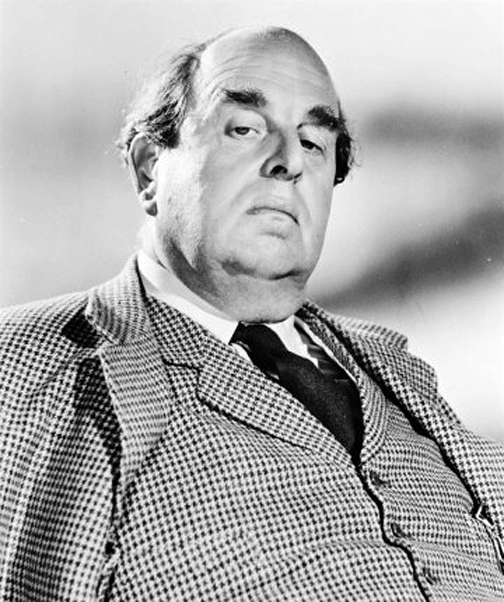

Robert Morley opened the door and stood inside, beaming and nodding and making desperate gestures with his right hand, which held a large pocket-handkerchief.

Although his mouth opened and closed, no words came out. At last he raised a finger dramatically into the air and we stood in silence until a thunderous sneeze took place. Morley honked copiously into the handkerchief and a look of relief spread over his face. “Do come in,” he said graciously. “I’ve got the sniffles, but it can’t be helped.”

The sounds of a television program drifted back over his shoulder as he led the way into his hotel suite. “Rather a nice room, don’t you think?” he said. “This is only the second time I’ve been to Chicago. The last time I went round and saw everything. Mrs. Wrigley’s mansion, you know, and those curious flats over a boathouse. Marina City, I believe.”

He settled himself on the sofa, a tall and round man with fierce eyebrows and a mouth that seemed to hold the universe in question. He wore a shapeless brown pullover sweater and looked, on the whole, more comfortable than he had in the white linen suit he wore in “The African Queen.”

“If it weren’t for the sniffles.” Morley said, “I would have taken you horse racing and we’d have made some money. Conversation and betting on the horses are my only consolations, you know. When I was in Washington – I say! Look at that!”

On the television screen, David McCallum had leaped from a rooftop into a speeding auto. Morley smiled as if to apologize. “The Man from UNCLE is a great help, isn’t it?” he said.

“These wretched publicity tours would be impossible without the telly.”

But his nose had started to twitch again, and the warning finger went up in the air. He sneezed. “God bless me, God bless me,” Morley said. “If there is a God, of course. Probably isn’t. Can you imagine going to heaven and meeting all the dreadful bores you’d spent a lifetime being uncharitable to?”

He pondered. “Of course, I can imagine myself going on to Heaven,” he said, “But nobody else. God and I shall be all by ourselves. I say, shall we eat?”

He stood up and began nosing about the room, unearthing a suit jacket and his glasses. “I don’t want to go outside with this cold,” he said. “Isn’t there a restaurant downstairs?” There was, we told him, The Pump Room.

Well then let’s eat there, by all means,” Morley said. “Is the food at all decent?” We said we’d never eaten there.

“Then let’s give it a whirl.” he said, delighted by his inspiration.

Morley found a place on the crowded elevator, and stood with his hands clasped behind his back, scrutinizing the floor indicator. At last, his eyes still fixed above the door, he returned to his earlier thought: “Surely you don’t suppose all the bloody bores on earth will carry on in heaven too. What’s a heaven for?” The others in the elevator looked sideways at him.

He found a stool at the Pump Room bar, ordered a whiskey sour, and looked around in astonishment.

“Rather a nice room,” he said. “They’ve made a real try.”

“Mr. Morley.” said a beautiful young lady sitting at the bar, “I just want to say I think you’re wonderful.”

“You don’t say?” Morley replied, beaming.

“I adored you in ‘Beat the Devil.’ And everything else you’ve done.”

“Oh yes, ‘Beat the Devil.’ Liked it, did you? You know, that was the first high camp film ever made. I must admit I’m responsible for the entire high camp movement. After I had looked at the script, I told John Huston that it was so badly written the whole film would come to pieces unless we played it as a farce. That’s why we were forever opening and closing our suitcases.”

“I see,” said the beautiful young lady.

Morley leaned away from her and lowered his voice. “I say, do you suppose our table is ready?”

Safely installed at a table overlooking the room, Morley polished his glasses and peered around. “You know, I’ve never seen that movie or any other movie I’ve been in,” he confessed. “I don’t like seeing myself. I haven’t even seen myself in the mirror for 20 years.”

The menu came, and while Morley was studying it a waiter walked past with a steak sizzling on a flaming sword. Morley started back in alarm.

“That’s the silliest way of serving food I can imagine,” he said. “Look, the meat is so far from the fire that it makes no difference anyway. Just as well. What self-respecting chef would allow his steak to be burnt on a flaming skewer after he’d finished with it?”

He looked at the menu again. “I suppose I’d best have the chicken,” he said. “At least they don’t praise the food here before they serve it to you. In so many American restaurants, you know, it’s difficult to tell what the menu is even describing. The people who write the menus get so lathered up in praising their 20-ounce, tender and juicy, corn-fed whatever-it-is that you suspect they’re not quite certain themselves.”

He surveyed the room. “You Americans always have to praise everything you do, he said. “The war in Vietnam, for example. Why can’t you just fight the bloody thing and not go about insisting the Vietnamese are enjoying it?

“That’s what we British can’t comprehend. We have a history of colonial wars, and we understand them. We could understand this war of yours if you were getting something out of it – profit or prestige, you know. But it’s a senseless war. If you ask me, Expo 67 ought to put up a pavilion to napalm bombs, and another to famine, and so on. That’s a part of man’s work, too.” Morley gave his order – Chicken, crabmeat, asparagus tips – to the waiter, and brightened considerably. “You must forgive me,” he said.

“Whenever I get a bad cold it always depresses me and I go about mooing like a fatalist. Actually, I’m just the opposite. Take the theater, for example. I like plays about the rich – about beautiful people. Happy plays. I can’t stand all these plays about dreary people. ‘Marat/Sade,’ for example. That was a dreadfully grubby play. I don’t like madness put up for the penny peep show.

“And ‘Waiting for Godot,’ there was another one, unless you like plays about people scratching themselves and picking off lice and smelling their boots.”

Morley said perhaps his attitude to plays reflects his approach to acting. “When I started out 40 years ago,” he recalled, “we never talked about acting. Acting was something we did naturally. We didn’t talk about it. We talked about card games, the horses, and girls.” In his new book, “Robert Morley – A Reluctant Autobiography,” he describes the first 10 years or so of his acting career, when he toured the provinces playing a series of “responsible gentlemen.” Was this the period he was referring to?

“Yes, I suppose it is,” he said. “In England the book was called ‘Responsible Gentleman,’ you know. But over there the term means something very particular. In drawing-room comedies, a Responsible Gentlemen is lower than the romantic lead but higher than the butler. That was me. And it still is, in a way.”

Morley sighed. “I’m disappointed in my own character,” he said. “I could have done a great deal more.”

In what direction?

“In every direction,” he said. “I’m a bore, for one thing, and I should have liked to be interesting.”

Surely he wasn’t serious?

“Oh, yes.” he said. “I’m a bore. So are a great many middle-aged actors. I’m a bore because most of the time I don’t interest myself. I can’t believe I’m going to start a story, but I do. And then I push ahead and finish it, and I’ve heard it a hundred times. But I suppose one is a bore or one is not a bore. It doesn’t matter.”

He picked up a copy of his autobiography and paged through it. “To tell you the truth,” he said, “I haven’t read it since I finished it a year ago. I was rather surprised with it after I wrote it. Somehow my life turned out differently than I had expected, and I didn’t realize it until I had to write it down.

“How does that poem by Kipling go? Once in my life I glimpsed a star, da dum, da dum, da dum, something, something, I have not loved, and dare not die . . .”