Robert Blake said he was fed up with being interviewed and smiling at strangers. He wanted to go someplace and listen to loud music. Fate led him to The Store, that famous Rush Street place where all the young folk congregate who aren’t getting any younger.

This girl recognized him from the movies and came over and sat down next to him and smiled.

“I’ll bet you’re an airline stewardess,” Blake said. “Well,” she said, “you’re right. But how did you know?”

“Something about your stewardess pin,” Blake said. The girl said that was very clever. She added that although she was an airline stewardess at the moment, she harbored ambitions of someday being in the movies. Blake, who is happily married, does not look exactly like the kind of guy girls would flip over from across the room. Unless they knew he was a movie star, maybe. And who wants to meet that kind of girl? Blake has figured out that girls who leap across the room and into his lap are not necessarily interested in him, and so he has invented a little game to play in these situations.

“Yeah, well, I guess I might be able to introduce you to a couple of people in Hollywood,” Blake said. “Why don’t we, uh, go someplace quiet and talk about it?” Just like that. Not very subtle.

“Oh, my,” said the girl, too taken aback even to flutter. “I’m afraid you misunderstood.”

“No,” said Blake, “I wouldn’t put it that way. I would say I did understand.”

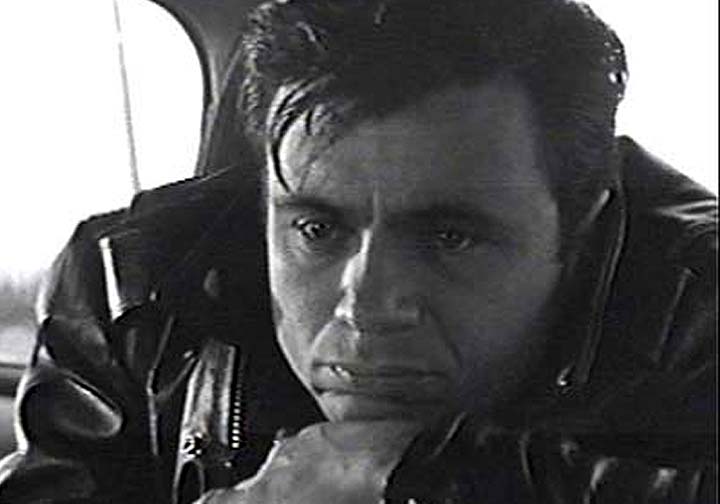

He looked at her hard, from beneath mean eyebrows. People who know him call it his Perry Smith Look. He perfected it while playing one of the killers in Truman Capote‘s “In Cold Blood.”

The girl departed, permanently disillusioned about Robert Blake, the famous movie star. End of interlude. Someone said he should have been kinder to her.

“She wasn’t being kind to me,” he said. “I called her bluff, you let these people get under your skin and you’ve had it.”

Well, that was the way the weekend went for Robert Blake. He left behind a lot of friends and a lot of enemies, which is unusual. Most movie stars who visit Chicago to promote a film leave behind a lot of people who couldn’t care less. Blake is an original, I guess you’d say. He says what’s on his mind, and he doesn’t worry a lot about whether he’s impressing people. He may be the only unemployed actor in history to turn down an offer from David Merrick to star in a new Tennessee Williams play.

But when he finally does sign a contract, he pledges his loyalty to the project at the same time. Although most film stars spend their days talking about themselves, their dogs, wives, next pictures, favorite recipes and hidden genius, Blake spent the weekend talking about “In Cold Blood” and its producer-director, Richard Brooks.

“Listen,” he said, “you don’t know what this guy went through for me. He kept telling them he wanted to cast me as Perry Smith and Scott Wilson as Dick Hickock. And the front office kept saying sure, sure, now get Paul Newman on the phone. Brooks had to fight every inch of the way.”

Blake talks softly, with pauses between his sentences, as if testing every word for truth. He is a compact, intense man of 32 and bears a startling resemblance to the man who walked into the Clutter home near Holcomb, Kansas, in 1959 and shotgunned four people to death. After that murder, of course, Truman Capote flew to Kansas and began the research that led to “In Cold Blood.”

“This was a big book with a lot of money riding on it,” Blake said. “It cost a big pile just to buy the rights. And so naturally the studio wanted Brooks to protect their investment, You know, hire established box-office stars, shoot in color, all that jazz.

“But brooks didn’t want it that way. To begin with, he insisted on black and white. And he was right. It would have ruined this film to shoot it in color. Every second had to seem real – and, you know, the funny thing is that black and white always seems more real than color.”

He stopped for a moment to regain his train of thought. “Oh, yeah. So black and white was the first thing. Then Brooks said he wanted to shoot in Kansas, on location at the scene of the crime, right there in Holcomb and in the Clutter house.

“I remember he said at the time that it might make trouble if he went to Kansas. But look at it this way, he said. If we shot it in Nebraska, people would say, ‘Isn’t that just like Hollywood? It happens in Kansas and they shoot it in Nebraska.'”

Blake sipped a double Jack Daniels on the rocks – his usual order – and smiled.

“And then the third thing was, he felt the actors had to be unknown. Especially the killers. It would be a sacrilege to have Marlon Brando creeping around the Clutter house. So he held out for Scott and myself, even though we meant nothing, absolutely nothing, on the marquee. I really respect that.”

Blake soft-peddled his own contribution to the film, although he has been mentioned as a possible Academy Award nominee. “This was a director’s film, pure and simple,” he said.

“Richard Brooks is a film author. That’s a man who retains complete control of the whole film in his own hands and then takes full responsibility for the final product. He didn’t just direct this picture. He wrote it, cast it, produced it, fought for it, edited it and lived and slept with it for months. This is his film. I’m just some actor in it.”

It was this candor which won Blake respect during his weekend here. But it also occasionally led him astray from the sunny paths of smiling image-building. After he explained his theory about black-and-white photography to a radio interviewer, he was asked if people wouldn’t expect color (red, anyway) since the word “blood” was in the title.

“There isn’t any blood in this movie,” Blake said. “You haven’t seen it, have you?”

Again, during a dinner party, he allowed himself to be absolutely honest. Among the guests were Bosley Crowther, recently retired after 29 years as film critic for The New York Times, and Al Horwitz,

associate producer of the film.

“Look,” said Blake, “if you want to interview me, see me tomorrow. This is all very nice, and all these people are nice, but if you want to talk about Richard Brooks and the film he made, I can’t do it while all this is going on.”

Because this attitude is honest and not a pose copied from Marlon Brando, it wins Blake admiration instead of resentment. He is likely to follow up a burst of candor with another one: “I’m still learning this interview routine. First I went to Denver and now Chicago. I don’t know what I’m doing. I figure if I just level with people, that will work better than if I pretend I know what’s going on.”

So far, it has. But Blake’s single film role in “In Cold Blood” has not pulled him permanently out of the woods. He is the kind of actor who will either fall back into relative obscurity or gradually become a legend like Rod Steiger – another straight talker who operates on sheer talent instead of press agentry. It’s a tricky way to build a career, and not even Blake is sure what he will do next. In any event, he won’t be in the Tennessee Williams play. He didn’t like it.