It was a night in New York to hover over a bottle of burgundy, one’s elbows on the table and talk of human love, of myth, of decency…and incest. They had not all seemed to belong in the same sentence before tonight, but now – well, “Murmur of the Heart” is not an ordinary film. Hardly.

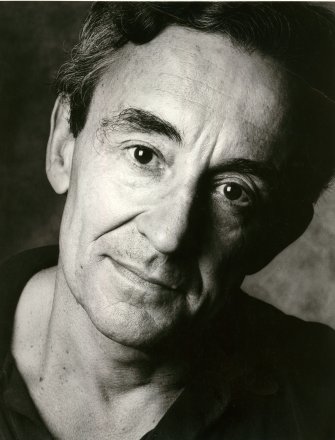

Louis Malle, who wrote and directed it, rolled his wineglass back and forth between his hands, and answered the obvious question first: “Just because the movie is about incest does not make it autobiographical. Yes, I have a mother…but that does not make me unique.”

His film, now at the Cinema, is almost impossible to describe without using terms that sound sensational. Yes, it is about incest between a mother and her son. But, no, that isn’t really what it’s about at all. It’s about a moment, a passing, whimsical, silly, serious moment on a young man’s journey into manhood. It is about a murmur of the heart, “La souffle au coeur,” as the French title has it, and it ends on a note so perfectly right that you leave this movie about incest feeling good inside.

“My brother and I have been playing a little parlor game,” Louis Malle said. “We ask ourselves how other directors would have ended this movie. What Fellini would have done. Bergman. Antonioni. Bergman might have ended it with dark recriminations, with cold northern guilt. Fellini…”

Malle shrugged. “Well, Fellini,” he said. “There is always Fellini.”

Louis and his brother Vincent, who produced the film, were sitting in a corner table of The Ginger Man, an expensive French restaurant masquerading as a down-home saloon with a touch of Irish grime. The

restaurant is just across the street from Lincoln

Center, where “Murmur of the Heart” had recently been shown in the New York Film Festival. The film’s reception had been very warm, but strange. People who had seen it had this compulsion to explain to you that the movie was about incest, but about a decent kind of incest. You know?

Louis and Vincent were enjoying The Ginger Man very much. Although they are both small and slender men, they love to eat and drink, and now they had a movie distributor to pick up their bills. They were horrified: They had spent more than $100 for dinner the night before. They were delighted: They had spent $75 for lunch, with a great wine. Unlike many movie people, they had not lived much in luxury, and among other things they liked about having sold a film in the American market was the free lunch.

“Murmur In the Heart” is the first commercial success in a long time for Malle, who is 39 and became one of the founders of the French New Wave in 1958 with his controversial film “The Lovers.” After that came a critical but not a commercial success, “Zazie dans la Metro” in 1961. In 1965, there was the disastrous “Viva Maria,” with Bardot and Moreau. And then not much at all in the feature film field. Malle turned to a series of brilliant documentaries, including one on starving Calcutta.

“And then, one day, I was sitting in the country and thinking about movies,” he said. “I had half a dozen projects, I was going to do this, to do that…and suddenly this idea came to he for a film about incest. It was almost a daydream. I went home and wrote out 60 or 70 pages in a few days. I showed them to friends. I got a warm reaction, I decided to make the film.”

But there were some doubts about the subject…

“It was a dream, a story, a made-up tale. It was not about my mother, of course. But it was about a kind of idealized fantasy mother [that] young boys hypothesize. When we are young, the Oedipus complex thing is like a joke. It takes years to discover that it is real, that there is a dream ideal, an initiating mother, in our subconscious. The movie is about that sort of childlike dream.”

He set it in the French provinces of 20 years ago, at a time when the Indo-Chinese War was behaving disastrously for the French, and when provincial

respectability was more firmly established, thus more amusingly shocked. He wrote it about the youngest, brightest of three brothers, and about their mother. She is an Italian, full of life, closer in age to her sons than to the husband who shocked his bourgeois circle by marrying her. Yet he loves her. He is a doctor, and they make a good couple, wise and humorous about love.

The entire movie, in a way, is a preparation for the moment of incest. And yet when it comes it is so unsensational, so quiet, that it can almost be

described as a moment of fondness.

“I didn’t feel like going any further in this scene with the boy,” Malle said. “He was not a professional actor, his reactions were sometimes unpredictable, and, besides, if I had pushed the scene any further it would have destroyed the tone of the movie.”

Tone is the hardest thing to get right in a movie, he said. “When you are working on a script, the story itself is not difficult. You say this would happen and then this, resulting perhaps in this. And the dialog you make as true as you can. But you must find the note, the correct key, for your story. If you find it, everything will work. If you do not, everything will stick out like elbows.”

So he did “Murmur of the Heart” as a human comedy, about growing up and losing innocence. “The problem was to somehow de-dramatize the highly-charged emotional materials we were working on,” he said.

“They were so loaded they could have destroyed the whole balance, the whole structure of the movie.” What he has achieved is a film with such a delicate sensibility that everything works, nothing sticks out.

People keep asking why they don’t make family movies anymore. Well, “Murmur of the Heart” is a family movie with a vengeance, you might say. And you do walk out feeling warm. But it is about incest. But not really. You know?