The way it happened that he came to Chicago, Alan Arkin said, was that after he quit singing with the Tarriers he fooled around in New York for awhile, a few acting jobs and a few office jobs that mostly fell through because he couldn’t stand working in an office, and then he went out to St. Louis to work with an improvisational group.

That group had its genesis in Paul Sills’ original Compass Players in Chicago, and Sills saw Arkin working in St. Louis and said if he wanted a job he should come to Chicago and join the new Second City company.

“I went back to New York but I got fed up looking for work, so, what the hell, in 1960 I came out to Chicago,” Arkin said. “I lived in a room on a corner of Wells and Lincoln. It was big enough to put a bed in. I was making more money than I had ever earned on a regular basis in my life – $125 a week – and it took me six months, no kidding, to get out of debt.”

Second City was the jumping-off point. When Arkin returned, at last, to work in New York, it was with Severn Darden and Barbara Dana in a Second City company that did three months on Broadway and a year in the Village. Then he went back up to Broadway in “Enter Laughing” and “Luv,” and one thing led to another. Although he was busy all the time on his own projects, including the brief film gem “That’s Me,” which he did with Andrew Duncan, another Second City graduate, the next time he really came into view was as a submarine officer in “The Russians Are Coming, The Russians Are Coming.”

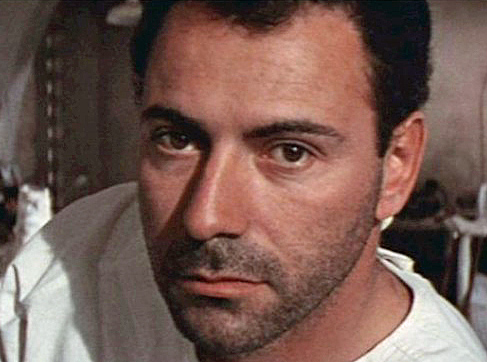

And, the thing was, he kept coming into view in that movie. His face, frank and kind and filled with pity that the world had to be filled with so much confusion, kept appearing out of conning towers and through windows and around corners, and he almost literally spent the whole film slinking around a New England fishing village, seeking aid for his grounded submarine. It turned out to be Arkin’s film. Even Arkin says he saw it nine times. It was his first major film role, one that won him a nomination as best actor in the Academy Awards.

And so Monday night, when they telecast the Oscar show from Hollywood, and between Bob Hope and Kim Novak the cameras pan the audience showing the nominees looking tense and uncomfortable, there on the screen, with Paul Scofield and Richard Burton, Steve McQueen and Michael Caine, will be our Alan Arkin, late of Second City, late of Wells St. And if, perhaps, as the evening grows late he runs his finger around the inside of his shirt collar and adjusts his tie more than is absolutely necessary, well, who knew seven years ago that it would come to this?

“But, look,” Arkin said a few weeks ago. “I’m in Hollywood now, making a single movie for a lot of money, but I don’t consider myself tied to this geographical location for all time. I’m trying to amuse myself to the best of my ability. There are a lot of other things I want to do. I would like to have a movie under my own control sometime, and see what could be done with it. Who knows? Maybe Hollywood will make an improvisational movie someday.”

Right now, Arkin is working at Warner Brothers, co-starring with Audrey Hepburn in a psychological thriller, “Wait Until Dark.” He came off the set dressed, as he often is, in khakis and a sport shirt, a light jacket against the coolness of a Southern California 4 o’clock, and loafers. It was a costume similar to the one he wore in “The Love Song of Barney Kempinski,” the television play last September in which he played this Brooklyn cabdriver who is just like the guy everybody knows who hates work, see, but he has to work twice as hard as anybody else just to avoid it.

Arkin, on the other hand, works twice as hard as anybody else just to avoid not working. “I gotta keep busy,” he said. “I’m not happy unless I’m working on two, three things.”

He is involved right now in preparations for a low-budget film version of Carson McCullers’ novel, “The Heart is a Lonely Hunter.” Filming will start in the autumn. When he finishes “Wait Until Dark,” he’ll leave for London to appear as Inspector Clouseau in a comedy, taking the role created by Peter Sellers in “Pink Panther” and “Shot in the Dark.”

And then, sometime in 1968, he and Mike Nichols hope to finally get rolling on “Catch-22,” in which Arkin will play Yossarian. Nichols, who left Second City before Arkin joined the company, will direct Joseph Heller’s incredibly complex, almost baroque, novel of World War II. Getting the screenplay into shape is another matter, like boiling down the Democratic National Convention into a 60-second TV spot without leaving out Walter Cronkite.

In his brief movie career so far, Arkin has resembled in his method an intense Sellers, employing both improvisation and offbeat characterization. In “Wait Until Dark,” he plays four characters, and in “The Heart is a Lonely Hunter” he’ll play a deaf-mute. As for Yossarian – gluk! Who can possibly picture the formidable Yossarian? Arkin can. Yossarian looks like Arkin. And so he does. Or at least he looks more like Arkin than like Tony Randall. Anybody could figure that out.

Arkin is pleased to look like Yossarian, and a Russian submariner, and a cabdriver, as long as all of these people do not look too much like one another. “They’re only too happy to jam you into a mold,” he said. “A product is most easily sold when it has an identity. So they wrap you all up and put a label on you. And then that’s what you have to be. But what I’m looking for is the opportunity to explore what I can do, probing the limits, learning.

“That’s the sort of thing we did at Second City. The Chicago period was terribly important to me. Before then I had wasted a lot of time. The time I spent singing with the Tarriers, for example – the Banana Boat period – was like a year’s hiatus. So then Paul Sills said come out and work.

“At first I thought, Chicago? I wanted to make it in New York. I thought if I went out to the Midwest I’d be burying myself. But I was wrong.”

The Second City classes of the early years are legendary now, but they weren’t legendary then. They were unknowns, trying to figure out every night what improvisational theater should be. Nobody knew, because Second City was the first improvisational company in the country, creating its own genre with Paul Sills directing in pleasure and pain and Viola Spolin explaining that theater was a game and so you had to play it.

If a bit worked, the company would keep it in, try it the next night, doing it differently. Every weeknight, after the show, they came out on the stage and took suggestions from the audience and tried to improvise scenes right on the spot.

“Improvisation sometimes seemed more like jazz than acting, like verbal jazz,” Arkin said, “with the actors playing a theme back and forth, and then introducing another theme, incorporating it, somehow trying to work their way all together to a meaning of some kind, or at least a conclusion. We had the opportunity to push ourselves in any direction.” The thing was, Arkin said, it was the right time for Second City. There was ferment all through the South, boiling over into the courts, a seething at the end of the long, dull if peaceful Eisenhower administration. “John Kennedy was elected President, and it seemed as if things might be opening up,” he said. “Everything was tied together, and there were targets for satire as well as tragedy. The moment was right for Second City.

“But now, I don’t know. It’s difficult to think of the times we’re living in now as bringing forth satire. It’s a whole different nation under Johnson. There’s got to be change, but you don’t have the feeling it’s coming. We’ve either got to get somebody very good as President, or somebody very bad.”

But Second City was never revolutionary, Arkin said. “It was always bourgeois, and we were all bourgeois. And all the people who went to it were middle class. What we did was we looked at ourselves and laughed, and proposed, for the moment, better motives and attitudes than we had. At the time, there was the feeling that maybe things were working out in that direction. Moral causes came back into fashion with the civil rights movement.”

Arkin said sometimes he thinks he can discern stirrings of the same sort on an international level. “It’s a funny thing,” he said. “Ten years ago, nobody went to a foreign film. Now everybody does, and not just to British comedies, either. Czechoslovakian films, Japanese films, Indian and Russian and Scandinavian films. A director like Ray literally opens up India to us; we simply didn’t know India before the way we do now.

“I think maybe a lot of the antiwar feeling among college students stems from this. When you can get a real feeling of how people in another part of the world live, you don’t want to kill them. They’re not abstract anymore.

“You can begin to see an amalgamation of cultures, the real beginning of one world. Ten years ago, it would have been impossible to imagine a Cockney singing group with a Southern Negro style and Indian and electronic music. I wonder if people have even noticed what a tremendous cultural signal the Beatles are.” But Arkin said he is not particularly heartened by Hollywood’s reaction to international culture. “A lot of the stuff they keep turning out is just the same old garbage,” he said. “I’ll tell you something. Until I made ‘That’s Me’ with Duncan, I didn’t know human beings could make movies.

What Arkin would like to do, someday, is make movies about urban situations. “The American city, the one thing that is part of everyone’s experience, is invisible in American movies today,” he said. “We make movies about the most preposterous subjects, but what about the millions of things that are going on in this country? In cities, in small towns, on farms? What really goes on in an American prison? “The problem is, Hollywood is not geared to spend so little money. Anything less than a couple of million is too small for Hollywood to bother with. And Hollywood is all there is, in this country, except for a few independents who have to hustle to get maybe $400,000 to turn out an intelligent film.

“There is no minority voice in the American cinema. Don’t talk to me about the underground, Andy Warhol and all that.”

Arkin permitted what could almost have been a grin to appear on his face.

“You know what Andy Warhol’s sole contribution to this country has been?” he asked. “He made Campbell’s Soup a household word.”