Arthur Penn, whose “Bonnie and Clyde” was a watershed in American film, died Tuesday night at 88. Gentle, much loved and widely gifted, he began life in poverty and turned World War Two acting experience in the Army into a career that led to directing in the earliest days of television and included much work on Broadway.

He was the man who cued Milton Berle to become “Uncle Miltie.” A pioneer of live TV drama, where his direction of “The Miracle Worker” with Patricia McCormack and Teresa Wright was a milestone. His “Two for the Seesaw” with Henry Fonda and Anne Bancroft was a Broadway hit in 1958.

But his Hollywood debut, “The Left-Handed Gun,” with Paul Newman as Billy the Kid, was a flop. His film “The Miracle Worker” was a success, but his next one, the avant-garde “Mickey One” (1965), with Warren Beatty as a Chicago nightclub comic, laid an egg.

After that film, Beatty was written off as a has-been in a celebrated Rex Reed profile for Esquire. Penn had trouble finding work. The two teamed up on “Bonnie and Clyde,” an unusual script by David Newman and Robert Benton; Faye Dunaway co-starred in the story of two Depression-era bank robbers. Warner Bros. mogul Jack Warner saw it and hated it. Legend has it Warner planned to dump it in Texas drive-ins until Beatty got on his knees before him and begged him to allow it to open at the August 1967 Montreal Film Festival.

There, disaster seemed to strike in the form of an angry review by the influential Bosley Crowther of the New York Times, who hated it. So did Joe Morgenstern of Newsweek, but he famously changed his mind in a later review. When it opened in Chicago, I wrote on Sept. 15, 1967: “This is pretty clearly the best American film of the year. It is also a landmark. Years from now it is quite possible that ‘Bonnie and Clyde’ will be seen as the definitive film of the 1960s.” I was right. On Oct 21, 1967, Pauline Kael praised it in a celebrated New Yorker review, her first for the magazine.

The film went on to make an explosive impact on American cinema, causing revolutions in both movies and fashion. “It was the French New Wave washing ashore in Hollywood,” the writer-director Paul Schrader told me. Influenced by Truffaut’s “Jules and Jim” (1962), it adopted an insouciant tone, combining violence and comedy in a way some viewers found offensive.

“Bonnie and Clyde” is the only film I know of that returned three times to first-run theaters in the Loop. The film’s 1930s women’s fashions came into style after Theodore von Runkle’s dresses put B&C on the cover of Time for the second time in a few months. And movies for decades after would be populated by Arthur Penn’s supporting cast of Broadway actors making their film debut: Gene Hackman, Michael J. Pollard, Estelle Parsons and Gene Wilder.

In a London interview at the time, Beatty told me: “Out in the bush leagues, the theater owners, they read the Times. For them, Crowther is God. Everybody in the world can like a movie, and if Crowther doesn’t, he kills it.” Hollywood, he said, “is old, old, old.” He posed a question. “I’m 28 years old,” he said. “I’ll give you five seconds to name me another Hollywood leading man under the age of 35.”

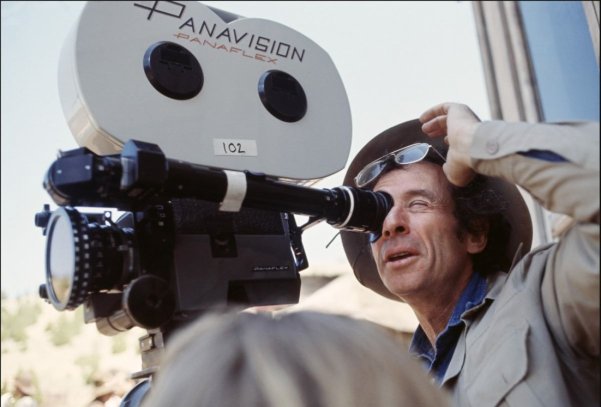

After “Bonnie and Clyde” made its impact, Arthur Penn established himself in the top rank of American directors with such films as “Alice's Restaurant” (1969), “Little Big Man” (1970) and the great “Night Moves” with Gene Hackman in 1975. He had less success after that film.

And how did Milton Berle became Uncle Miltie, first superstar of American TV?

“My floor director in those days was Arthur Penn,” Berle told me in Toronto in 1980. He would squat under the camera and give me signals so I knew how much time I had left. One day I think the show is over and look down at Penn, and he’s holding up eight fingers. That means I’ve got eight minutes to fill. I ran out of jokes and started talking to the kids: ‘Time to go to bed, kiddies! Uncle Miltie says goodnight!’ It stuck.”

Penn was born Sept. 27, 1922 in Philadelphia. His parents divorced when he was three, and he and his brother Irving (the famous photographer) lived with their mother in New York and New Jersey as she raised them in poverty. He is survived by his wife, the actress Peggy Mauer, a TV director son Matthew, a daughter, Molly Penn, and four grandsons. His brother Irving died in 2009.