Johnny Cash had one requirement for the star of “Walk the Line“: “Whoever plays me, make sure they don’t handle the guitar like it’s a baby. Make them hold it like they own it!”

This was during a “real Southern breakfast” that John and his wife, June Carter Cash, cooked up for James Mangold and his wife, Cathy Konrad, who were going to direct and produce the movie.

“We went down to Hendersonville and checked into the hotel,” Mangold remembered, “and John came and picked us up in the lobby. Not dressed in black. Just jeans and a checked shirt. At their house, John and June sang grace, holding hands. And John told us stories about his early days in the music business.”

“I was sent by Sam Phillips of Sun Records with a record in an envelope, for a disc jockey to play,” Cash told them. “The deejay dropped the record, and it broke. I called up Sam and I was about in tears. ‘John,’ he said, ‘I got a thousand more.’ In those days there was no ‘Inside Edition’ so every 20-year-old knew how records were made.”

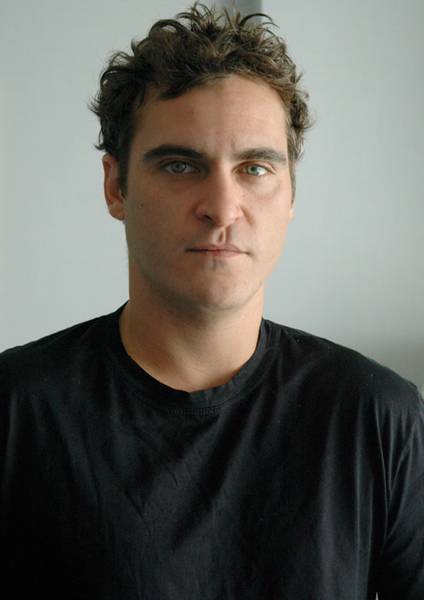

This would have been around 1999. Mangold had been shopping the Johnny Cash biopic around Hollywood with no luck. Even after he had Joaquin Phoenix and Reese Witherspoon on board to play John and June, he was told the studios “don’t want to make movies about people.” William Goldman, the veteran screenwriter, had a gloomier analysis: “No one wants to make a movie that depends on you pulling it off.”

They want, in other words, to make movies that don’t need to be pulled off. Movies that are foolproof. Formula pictures, teenage action movies, video game adaptations, sequels. Last year, every studio in Hollywood passed on “Ray,” the biopic about Ray Charles, and this year it can be said that they all passed on “Walk the Line,” until Fox 2000 finally came through. What’s ironic is that “Ray” won an Oscar for its star, Jamie Foxx, and “Walk the Line” may get nominations for Phoenix and Witherspoon.

I talked to Mangold and Konrad at the Telluride Film Festival last Labor Day, and a week later I talked with Phoenix at the Toronto festival. The movie, which opens nationally on Friday, was well-received both places, and what amazed a lot of people was how well Phoenix and Witherspoon could sing — not “considering they aren’t singers,” but as if they actually were. When I saw the movie, I closed my eyes to focus on the soundtrack and convinced myself I was actually listening to Johnny Cash; the vocals were so convincing that when the credits rolled up, and Phoenix was credited with doing all of his own singing, I was amazed, and so were a lot of other people.

“I didn’t sing and I didn’t have any experience,” Phoenix said. “Not even in the shower. I worked with a voice coach for an hour and a half a day. I had to go down an octave. T-Bone Burnett, our music consultant, helped me a lot. John had an amazing range. In ‘Walk the Line,’ he changes keys with every verse. But it wasn’t really so much how he sang as how he acted the songs.

“Then there was the challenge of showing him finding his voice. In biopics, we always see the finished product, but not the development. But in his early albums, John sings very differently than later on. How does he find his voice, between his early 20s and his 30s? How did he discover his sound?”

For Mangold, the most courageous thing about Phoenix’s performance is, “He plays the growth. There is that early audition scene where he starts out lousy, trying to sound like somebody on the radio, and by the end, he is singing in his own voice.”

That’s the scene where, after weeks of trying, Cash gets an audition at Sun Records, where the legendary producer Sam Phillips launched Howlin’ Wolf, Jerry Lee Lewis and Elvis Presley. He listens to Cash listlessly grind through a spiritual, stops him, and asks him if he has anything of his own he can sing. Cash does. He wrote “Folsom Prison Blues” while he was serving in the Army in Germany. He sings it, and in that scene, Phoenix shows Cash moving verse by verse toward his sound.

“Sam Phillips was like a great director,” Phoenix said. “He helped develop the idea of the singer-songwriter. Country music took a hit with Elvis, and the country singers were wondering, what do we do? Sing like Elvis? John brought back the storyteller side of country, as opposed to the Nashville sound. What you feel with John is empathy.”

Mangold agrees. The director’s earlier titles include the overlooked “Heavy” (1995), Sylvester Stallone in “Cop Land” (1997), Winona Ryder and Angelina Jolie in “Girl, Interrupted” (1999) and the weirdly wonderful time travel romance “Kate & Leopold” (2001). “Walk the Line” is his first venture with a music-based film.

“Sam Phillips was kind of like Lee Strasberg at the Actors’ Studio,” he said. “He was doing the same kind of thing with Johnny Cash that Strasberg was doing with Brando, Newman and Dean. He was asking them to call on real human experience more than a kind of glamor.”

June Carter, he said, actually studied at the Actors’ Studio: “She grew up in a well-adjusted family, she was familiar with show business from the time she was born, the Carter Family was royalty in country music. She was acting more than people knew. There were two Junes. Onstage, she liked to joke and clown, because she wasn’t as confident of her singing as she deserved to be. Offstage, she was a pro who knew how the business worked.”

Carter and Cash, who both died in 2003, were “excited” that Witherspoon and Phoenix were going to sing in their voices. Cash’s only worry was about the guitar-handling. He had no objection to the frank way the movie handles his addiction to pills, and his battle to get clean with June’s help. That was all on the record, and inspires one of the movie’s best lines.

After he’s busted and spends some time behind bars, his father, who John felt he could never please, said, “Well, at least now when you sing that ‘Folsom Prison’ song, you won’t have to work so hard to make people think you been to jail.”