LOS ANGELES–There are three official movie nights at the Playboy Mansion. Friday nights are for classic films, Sundays for new releases, and Wednesday night for films chosen by popular demand. “You ought to drop in on Friday,” Hugh Hefner’s daughter, Christie, told me. “Hef does the notes himself.”

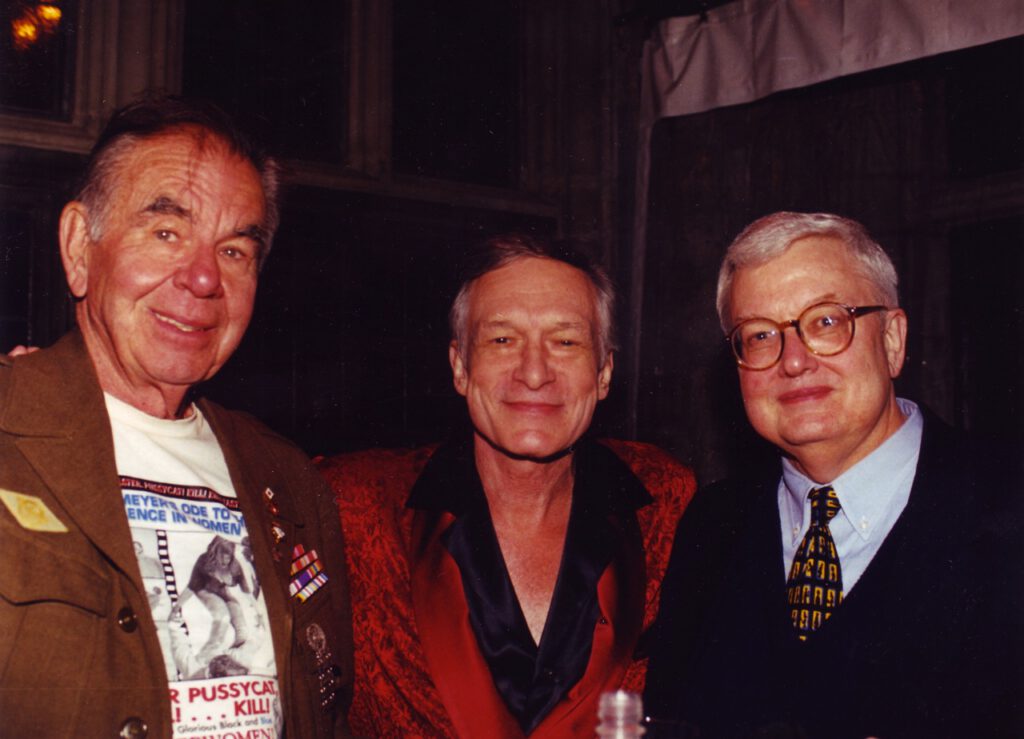

The mansion stands in Holmby Hills, west of Beverly Hills, but it could be in the English countryside, with its neogothic battlements and the fountain splashing in its forecourt. I brought along Russ Meyer, the celebrated filmmaker, who had photographed half of the first dozen Playboy Playmates.

We entered the entrance hall, which looked uncannily like a set for an elegant horror film. Straight ahead, overlooking the lawn, was a bar where I ordered a Diet Pepsi, official drink of the Mansion, and said hello to some of Hef’s regular moviegoers. Ray Anthony, the orchestra leader, was there, and Robert Blake, the actor.

Hef materialized, wearing his customary pajamas and smoking jacket. A glass of iced Pepsi was pressed into his hand without comment.

“What Oscar parties are you going to?” he asked.

“My wife and I will go to the Miramax party,” I said. “That’s always a lot of fun. And we’re invited to the Vanity Fair party…”

“So was I,” Hef said gloomily, “but I can’t go.”

“Why not?”

“They’re so strict with their invitations. You’re only allowed one guest.”

“So?”

“I’m dating twins.”

Russ Meyer’s face brightened. “You, sir, are a great inspiration,” he said.

“They’re going to be late to the movie,” Hef said. “One is at the hair-dresser’s. When one dates 22-year-olds, one pays the price.”

“Twins?” I said.

“Mandy and Sandy. Delightful girlfriends. Luckily they get along well with Candy, who I was dating when I met them.”

“So you might have three dates on Oscar night?”

“It was suggested that I walk in with one twin, leave her inside, and then walk in with the other one,” Hef said. “But how many girls can you walk in with?”

A gong sounded. “Time to eat,” Hef said briskly. Movie Night followed a tight schedule. The group, perhaps 18 or 20, drifted into the dining room, where a chef sliced prime rib onto our plates. Hef sat at the head of a long oval table. The seats on either side of him were reserved for Mandy and Sandy, but since they were missing, Russ and I were invited to sit there.

“I was here for the grand opening of the mansion,” I told Hef, remembering peacocks on the lawns and Playmates splashing in the grotto. “I wrote that you were the Gatsby of your time.”

Hef nodded thoughtfully. It occurred to me that considering Gatsby’s difficulties, this was not as high a compliment as I had intended.

“Since I started to date again,” Hef said, “after the divorce, we’ve been swamped by the press. Bill Zehme wrote a piece in Esquire. That started everything. Then we got the New York Times, the London Telegraph, the Los Angeles Times, Time magazine…”

“I read that Hollywood’s young turks are hanging out here now,” I said.

“Leonardo DiCaprio was here the other night,” Hef said.

I sensed, however, that Friday Night at the Movies was taken too seriously to permit the Mansion to be overrun by cover boys from Entertainment Weekly. The guests were members of Hef’s inner circle–heavy-duty film buffs, for whom these nights were in the nature of a devotion.

I quoted something Gore Vidal had written: That as he looked back over his life, he realized that he had enjoyed nothing–not art, not sex–more than going to the movies. Hef looked as if he could think of a modified version of that sentiment. “Okay, movie time!” he said, getting up. We filed into the Great Hall, where sofas were lined up facing a big screen. Two full-sized 35 mm projectors stood at the back of the room.

Hef waited, just slightly impatiently, until everyone was seated, and then held up a hand for silence. He produced a yellow legal pad and introduced the movie. “Hef does his own research every Friday afternoon,” Chuck McCann, the actor, whispered to me.

Tonight’s feature was “Treasure Island”–the 1934 MGM version, with Jackie Cooper and Wallace Beery. They had not gotten along well on the set, Hef told us. His remarks dealt with the four earlier silent versions of the story and the 1950 Robert Newton version, but he left out the 1972 version with Orson Welles as Long John Silver, perhaps as an act of mercy.

Meyer and I sat right behind Hefner. During the movie young women materialized in the dark and slipped in next to Hef. Mandy? Sandy? He gave them a smooch of welcome, and then returned his attention to the adventures of Long John Silver.

After the movie, Hef repaired to his private quarters. “Look at this,” Chuck McCann said. He led me into a passage between the walls, where we found a full-sized pipe organ. “It’s concealed behind a screen in the Great Hall,” he said. “Sometimes we show silent films with live music. ‘The Phantom of the Opera‘ was sensational.”

Hef reappeared, in a black suit and open-necked white shirt. We were introduced to Mandy and Sandy, who were wearing matching outfits with bare midriffs. They were on their way to a party. McCann, Meyer and I lingered, talking about the greatness of old movies.

Looking for the bathroom at the end of the evening, I wandered into the kitchen. It was enormous, with spotless stainless steel everywhere. On a shiny counter, two plates were laid out, wrapped in Saran Wrap. One held half a grapefruit, the other slices of tomato. Hef’s bedtime snack, I guessed. Living well is its own reward.

On Oscar night, after the ceremony, I co-hosted a TV program that included live reports from the various parties around town. There were six monitors facing me, and on one of them, just before midnight, I saw Hugh Hefner arriving at a party with Mandy, Sandy, and six other dates. Must not have been Vanity Fair’s.