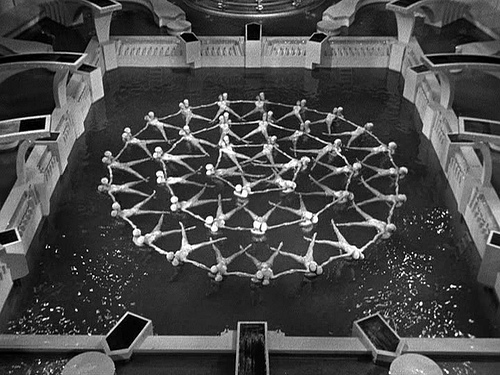

Just before the big production number in “Footlight Parade,” James Cagney says: “If this doesn’t get ‘em, nothin’ will.” What follows is the famous “By a Waterfall” sequence in which Dick Powell dreams of dozens of beautiful mermaids sliding and swimming down a waterfall. One of the little creatures, naturally, is Ruby Keeler.

Well, it got ‘em on Saturday night, when the Chicago International Film Festival opened its third season with a tribute to Busby Berkeley, the 1930s pioneer of the Hollywood musical.

Oh, it got ‘em, all right. Again and again. The audience was shown some two dozen Berkeley production numbers, strung end to end for three hours. And that probably wasn’t such a good idea.

Berkeley has long had a reputation as the creative genius and master mechanic of the 1930s musical. “Mechanic” he was. You’ve got to admire the sheer technical skill necessary to choreograph 100 dancing grand pianos. You respect the discipline needed to mold 100 beautiful blonds into a dance line of machine-like precision. Many of his numbers are stunning in the scope and cost of their production (reportedly more than $10,000 a minute). Hollywood will never again stage scenes on this scale, if only because wages and production costs prohibit.

But there is probably another reason why those mermaids will never swim again. Tastes have changed in the intervening decades, and audiences are no longer entertained simply by scope and excess. If you’ve seen one group of dancing girls making geometric patterns for an overhead camera, you’ve seen them all (and Saturday night, toward the end, I had the feeling that I literally had.)

Berkeley, however, wasn’t making his movies for us. He had a proven formula and a reliable audience, and he entertained. His audiences expected a Berkeley movie to have infinite parades of smiling girls, lots of expensive effects, trick camera shots, spectacular patterns on the screen, close-ups, of Dick and Ruby ever falling in love anew. Berkeley delivered magnificently.

And at the beginning of his career he was a pioneer and an innovator, because such extravagance had never been imagined before. He was, in a sense, testing just how far the movie musical could be pushed before it reached a point of no return.

The result of 180 minutes of Berkeley, however, was the impression that he didn’t improve and develop his original insight. His choreography remained geometric and sterile. His scenes were more often feats of engineering than creativity. Other American directors of the same period were moving in more imaginative directions; Fred Astaire’s “Harlem Bojangles” number in “Swing Time” (1936) was a brilliant demonstration by George Stevens that humor and timing were more entertaining than sheer excess.

Berkeley never did get over the geometry, unfortunately. In the early 1950s, the era of “An American in Paris” and “Singin' in the Rain,” he was still doing the same old tricks in movies like “Million Dollar Mermaid.” You know, line up the girls and have them all turn and smile at the same time.