Stanley Nelson didn’t leave for college without taking his father’s copy of Miles Davis’ game-changing 1959 album, Kind of Blue, along with him. The three-time Emmy-winning documentarian and cinematic chronicler of the African-American experience may have grown up a jazz fan, yet never in his wildest dreams did he envision himself directing a film about the legendary jazz trumpeter nicknamed the “Prince of Darkness”—that is, until a decade ago. He didn’t know much about the ins and outs of Davis’ life when first approaching it as the subject for a movie, and his process of discovery is shared by the audience during the engrossing, two-hour profile, “Miles Davis: Birth of the Cool.”

Nelson will be in attendance for the film’s Chicago premiere this weekend at the Gene Siskel Film Center, and recently spoke with RogerEbert.com about capturing the essence of Davis’ musical genius onscreen. The picture is chock full of rare archival footage, including a recurring glimpse of Davis practicing his moves in a boxing ring, not unlike De Niro during the opening titles of “Raging Bull.”

“There was something that was just so Miles about it,” recalled Nelson. “He was a boxer, but he also was aggressive. It always seemed like he was trying to fight against the world. Nobody had ever seen that footage before. It was shot by Miles’ great friend, Corky McCoy, who had been storing it in his basement.”

Allowing Davis’ voice to guide the film was of paramount importance to Nelson. For the narration, he drew upon the introspective conversation contained on over forty cassette tapes between the musician and writer Quincy Troupe, who coauthored Miles: the Autobiography in 1989. Since the quality of the audio wasn’t good enough for inclusion in the film, Nelson hired actor Carl Lumbly (“To Sleep With Anger”) to read selected excerpts of Davis’ words. Among the film’s most illuminating talking heads is Frances Taylor, Davis’ first wife, who died last November at age 89. Her recollections were so entertaining that Nelson admitted there were times he wondered whether or not she was pulling his leg (“I couldn’t tell if she was serious,” he told me, “but she was really funny, and she knew it.”). An entire film could be made about the passionate affair Davis had, nearly a decade before marrying Taylor, with actress Juliette Gréco during his time in France.

“For so many black musicians or black artists, there’s this tradition of going overseas to places like Paris and falling in love with not only the city but the way that black people were treated there,” replied Nelson. “It was just different enough that it meant so much to the artists. One of the great things about Miles’ story is how so many things fell into place. What he and Juliette had together was a real love story. He goes to Paris, falls in love, comes back, gets depressed, spirals down into heroin addiction, kicks the habit and gets to prove it during the concert in Newport that changes his career. These are not isolated events. They form the chain that joins together to become the story of his life.”

George Wein, founder of the Newport Jazz Festival, turns up to reminisce about how Davis’ 1955 performance of “‘Round Midnight” left his crowd of attendees spellbound, as we see snapshots of audience members drinking in every note of the song with their eyes closed. In order to most effectively portray each section of Davis’ career spanning nearly five decades, Nelson worked with a team of three editors. When I voiced my belief that documentaries are made in the editing room, the filmmaker couldn’t help agreeing.

“I’m a hundred percent with you,” affirmed Nelson. “A lot of our time is spent in the editing room. We must spend our time productively in order to put all the money and effort on the screen, and you need that time to try different approaches. For every single photograph in this film, we thought about whether it would be a push-in or a still shot. Lewis Erskine was the driving force behind each decision, though the other two editors [Yusuf Kapadia and Natasha Mottola] did so much work that they deserved to be credited alongside him. I don’t look over their shoulder while they work, but we talk about all of their choices between each cut and recut, so it’s a real collaboration between us.”

Every time the film moves ahead to a pivotal chapter of Davis’ life set in a new decade, Nelson provides an exhilarating stream of instantly recognizable, blink-and-you’ll-miss images to summarize the particular era.

“Our ability to absorb images at a faster rate has only increased in recent years, so I felt we could take that into hyperspace,” said Nelson. “I wanted to figure out how to set up an era, such as 1955, without stopping the film to explain, ‘This is the year Emmett Till was killed, and so on.’ I kept asking the assistant editor to speed up the sequence of images until I finally said, ‘Make it go too fast, and then we’ll pull it back.’ That’s the version that made the final cut, and it’s amazing how, even at that speed, you can pick out individual images like the Creature from the Black Lagoon. It almost gives you this subliminal sense of what it was like in those years, and it also picks up the pace.”

While being honored at the AFI Doc festival’s annual Guggenheim Symposium back in 2015, Nelson reflected on how his 2004 masterwork, “A Place of Our Own,” evolved from a film about the black middle class into an achingly personal portrait of his own family, an alteration prompted by feedback from his editor. I was reminded of this story when listening to Davis’ definitive observation that “if anybody wants to keep creating, they have to be about change.”

“One of the things that art allows you to do, and in some ways, forces you to do, is change and evolve, or else you’ll be making the same film or repainting the same picture over and over again,” noted Nelson. “It’s almost like art, in itself, makes you try to evolve. What can I do differently, how can I do something that’s better? For Miles Davis, it wasn’t that he had a drive to change. It’s not like he sat there and said, ‘Let me try to do something different.’ He just had to.”

Stanley Nelson will join Miles Davis’ nephew/bandmate Vince Wilburn Jr. for the following three screenings of “Miles Davis: Birth of the Cool” at Chicago’s Gene Siskel Film Center: 7:45pm on Friday, October 4th; 5:15pm on Saturday, October 5th; 2:30pm on Sunday, October 6th. For more information or to order tickets, click here.

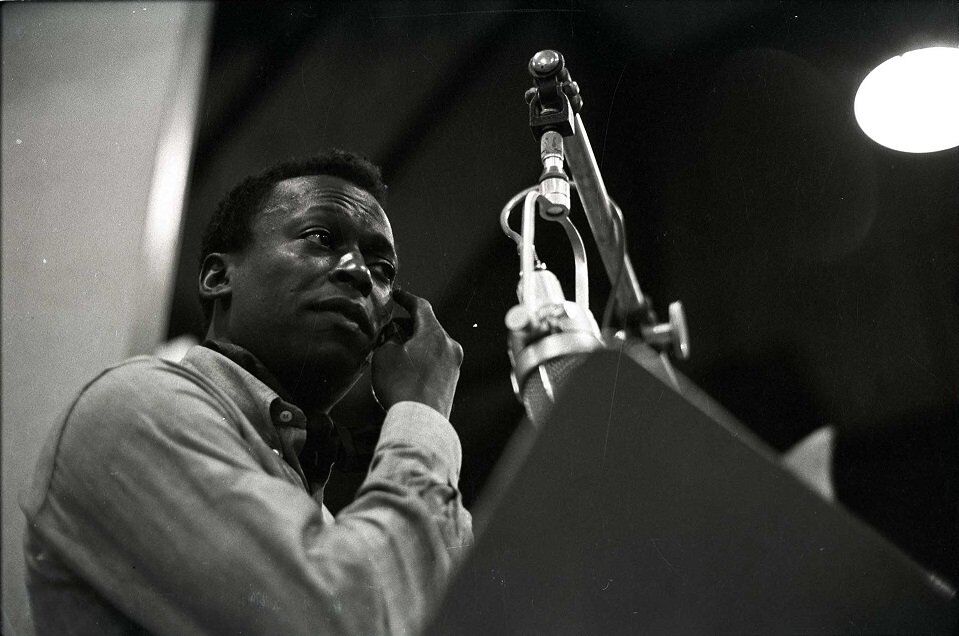

Header photo credit: Don Hunstein, Sony Music Archives. Courtesy of Abramorama.