Carmine Coppola‘s hand plunged into his coat pocket and emerged with a yellow Western Union envelope.

“This came this morning,” he said. “A telegram. From Gloria Swanson.”

Coppola wasn’t talking loudly, exactly, but his voice carried well, and at the other tables in the breakfast room of New York’s Sherry-Netherlands Hotel, heads turned in our direction. Coppola adjusted his glasses and held the cable at arm’s length. He cleared his throat. There was a hush in the room.

“Enthralled!” he read. “Et cetera, et cetera. Signed, Gloria Swanson.” He replaced the telegram in his pocket.

“Gloria Swanson has, I think, a silent film she would like to see revived,” he explained, more softly now. “I don’t know if her film is of the stature of this thing.”

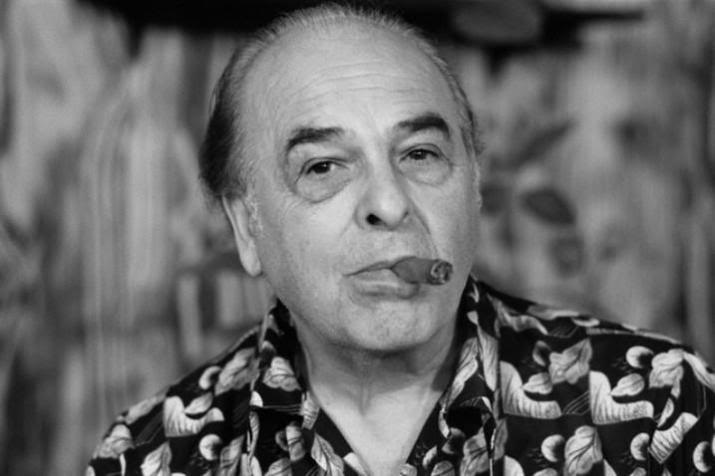

This thing was “Napoleon,” a 1927 silent film that had suddenly become the hottest ticket in New York, making a star out of the balding, powerfully built man who was sitting down to his breakfast.

“Eggs,” he told the waiter. “An omelet, make it with mushrooms, remember to bring me the hot sauce.”

The story of “Napoleon” and Carmine Coppola has become one of the best movie stories in years. The movie originally had a running time of more than four hours, but after its 1927 premiere it was never shown in the original version. Its director, Abel Gance, supervised various reconstructions and shorter versions of the footage, but the myth of the original epic film never died.

Film historian Kevin Brownlow plundered the film archives of Europe for all the “Napoleon” footage he could find and made some lucky discoveries of scenes that were thought to be completely lost. Then he rebuilt “Napoleon” into a reasonable facsimile of its original version, complete with the famous three-screen, hand-tinted triptych that ended it – an effect that anticipated Cinerama.

This version played to great acclaim at various small film festivals, and then movie director Francis Ford Coppola got the idea of presenting it properly, with a full orchestral score. He commissioned his 71-year-old father, Carmine, to compose the score, and in January the Coppolas presented “Napoleon” in Radio City Music Hall with Carmine conducting the American Symphony Orchestra.

“We hoped to play one weekend and maybe break even and pay for printing the scores,” Carmine Coppola remembered. “We had to extend for three weekends. We have been totally sold out. You’re talking about a $25 top price.”

The story is much the same here in Chicago, where “Napoleon” opens Thursday at the grand old Chicago Theater, a landmark movie palace that opened six years before “Napoleon” did. Carmine Coppola will be in the pit conducting a 60-piece orchestra and the theater’s own restored original Mighty Wurlitzer organ.

“Napoleon” was originally scheduled for four performances, Thursday through Sunday, but the demand for tickets has made it necessary to extend the run through the next weekend, April 30 to May 3. (Chicago tickets are pegged at $10 to $20, and can be purchased from Ticketron or by calling 977-1700.)

I went to New York in February to see Coppola and “Napoleon”, and it was one of the great moviegoing experiences of my life. On the screen, Gance’s 1927 original was breathtakingly sharp; the print has been restored remarkably well. It also moved well. There was a minimum of title cards and a great clarity of visual storytelling, and the legendary French star Albert Dieudonne held the screen as a Napoleon obsessed with France, with revolution, and with himself.

In the pit, Carmine Coppola conducted a score that he had composed in the romantic style of the great silent film scores of the 1920s. And a trick of lighting gave his performance a dramatic impact. The lights on his podium cast a shadow of the conductor onto the great domed Art Deco ceiling of the Music Hall, so that you could look up and see a gigantic shadow image of his arms beating time and his coattails flapping. It was the sort of movie memory that will not fade.

“But how,” I asked Carmine Coppola over breakfast, “how in the world at your age can you find the energy to conduct for more than four hours, with one intermission?”

“Twice I did it the day we had the press preview,” he said, “once in the afternoon and once in the evening.” He splashed Tabasco on his eggs. “I’ll tell you what it is. It’s strong Italian peasant stock. We’re a hardy people, you know. We’re out in the olive groves all the time, picking the olives.”

But there was more to it than that. Carmine Coppola has been on the road almost all his adult life, as a professional musician. There is a sense that he prepared all his life for an assignment like the “Napoleon” score.

“When I was a little boy there was no sound in the movies,” he remembered. “When I was about 11, my mother gave me a dollar for my birthday and I went to a big theater in New York – was it the Rialto? The Rivoli? The Roxy was just about being built then. The movie was “Thief of Baghdad”, with Douglas Fairbanks, who always insisted upon original scores for his movies. I remember so well it could be yesterday, the sound of the flutes and the oboes.

“I practiced the flute at home, listening to all my father’s Caruso recordings. I went to the tryouts for the B. F. Keith Boys Band, in our neighborhood. The director says, ‘Coppola, can you play the flute variation of the William Tell Overture?’ I could. We had the record at home. The director told me they were going to give me a flute and send me to a teacher, and that I could play with their band.

“You know, I don’t think my father had to spend $100 total for all my music lessons. I was always on scholarship. I studied at Stuyvesant High School, and then at Juilliard, where I was one of those whiz kids who graduated in three years. My first job, I played flute in the Radio City Music Hall, four to five shows a day.

“I got married. My wife was named Italia Pennino. She was the daughter of a famous Neapolitan folk music composer and publisher. He had nothing but boys, boys, boys, and he said if he ever had a girl he would name her after his country. Italia and I went to Detroit, where I conducted the ‘Ford Hour’ on the radio for four or five years. Our second son, Francis Ford Coppola, was born there, in the Ford Hospital, which is where he got his middle name. Then back to New York, an audition for Maestro Toscanini, and a job in his orchestra. My daughter, Talia Shire, was born then. I learned to conduct, just watching Toscanini.

“I told him I wanted to conduct. He told me I was a fool. I conducted all the same, at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, and then for David Merrick, conducting the pit orchestras for Broadway shows. I came to Chicago to conduct the orchestras for many shows, including Kismet, Stop the World, Half a Sixpence. I stayed at the Croyden Hotel and walked across the bridge and under the marquee of the Chicago Theater, where we are bringing “Napoleon”.”

Carmine Coppola’s musical career took a new turn when his son Francis became a famous film director and hired his father to do the orchestrations for “Finian's Rainbow” (1967). Seven years later, in 1974, the score by Carmine Coppola and Nino Rota for “The Godfather, Part II” won the Academy Award.

“That made me somebody to reckon with,” Coppola said. “Now I do a lot of work. “Apocalypse Now,” “The Black Stallion.” This conducting of “Napoleon” is one of the hardest things I have ever done. When you conduct opera, you control the stage. But with a film, the film controls you. There must be 50 or 60 sight cues in this film that the conductor has to hit exactly – things like school bells ringing. That film, that’s a tyrant up there. Everyone once in a while we get a rest while the organist takes over. Of course, we’re gonna try for an Oscar for this.”

After the eight engagements in Chicago, “Napoleon” and Coppola will visit several other big American cities. “And then,” said Coppola, his voice rising slightly again as he unconsciously took the stage in the breakfast room, “then we’re going to go on to Europe. Munich wants us. London. Paris is jealous that we resurrected “Napoleon” instead of them. This afternoon, I am speaking live by telephone, in Italian, to the Italian state radio network.”

He was hitting his pace now, his voice filled with enthusiasm. “I will tell them we plan to bring “Napoleon” to Italy. To Rome. To Venice, where I would like to present it outdoors in Piazza San Marco. In Milano, at La Scala. In Verona, in the Verona Amphitheater. We will march down Italy with this movie, taking up where Napoleon left off.”

“In Paris,” I said, “you will no doubt have Abel Gance, the director of “Napoleon”, in your audience. He is still alive at 92.”

“I’ve already met him,” Coppola said. ”He told me, before he died, he wanted the pleasure of seeing “Napoleon” shown to the world in the right way. Now he has that pleasure.”

“And he can rest in peace,” I said.

“Not at all! Certainly not! Now he wants to make a nine-hour film about Christopher Columbus, with Marlon Brando in the lead.”

“At 92 years old?”

“Absolutely.”