Dakar, a coastal West-African city flanked by the Atlantic Ocean, serves as an entry and departure port for souls with sights set on horizons beyond their grasp. Migration flows undisrupted through the waters even if what the tide brings in return is often bad news of lost vessels. On land in the Senegalese capital, those who remain go on, as best they can, while haunted by the intangible presences of one-way travelers.

That’s both reality for many countries in economic flux and the premise of Mati Diop’s beguiling first feature “Atlantics.” Earlier this year, the French-born filmmaker and actress (“Simon Killer,” “Hermia & Helena“), an artist acutely attuned to her biracial and bicultural identity, gained the landmark distinction of being the first black woman director ever with a project in the main competition at the Cannes Film Festival—a merit that’s simultaneously unfortunate for the lack of inclusion it illuminates.

Niece to celebrated Senegalese auteur Djibril Diop Mambéty (“Hyenas,” “Touki Bouki”), Mati Diop creates an eerie genre romance between soon-to-be-married Ada (Mame Bineta Sane) and construction worker Souleiman (Ibrahima Traoré) within a coming-of-age drama for an endlessly surprising narrative compound.

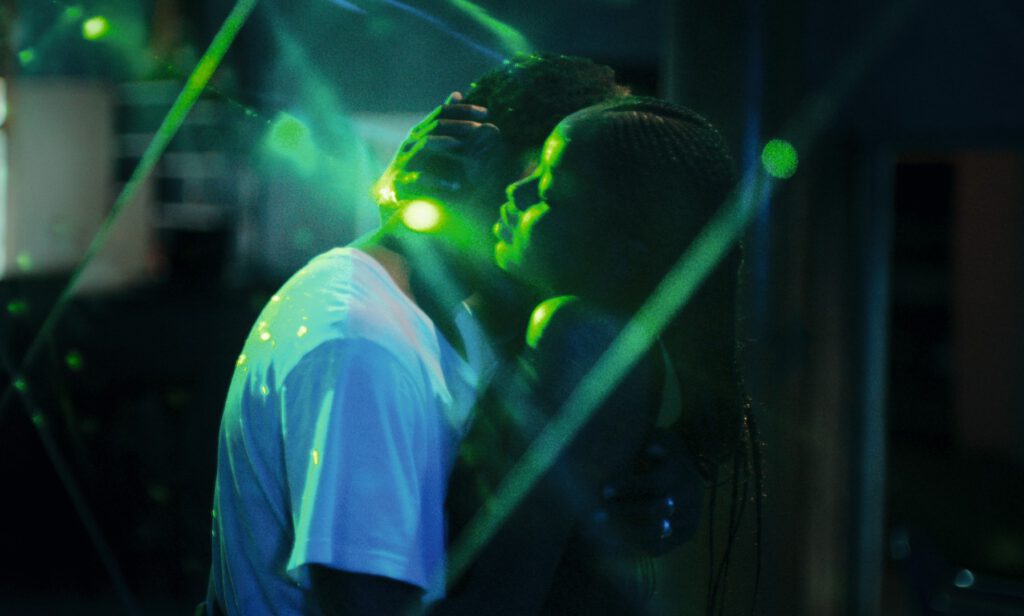

Possessed bodies may act as the physical manifestation of the culturally relevant and social justice subjects Diop gravitates towards, but the mechanics of her supernatural realm, which involves mirrors and gender swapping, also function marvelously from a fantasy standpoint. Magnificently transfixing, Diop’s ghost world is saturated with political implications, spiritual gravity, and subdued lyricism. Intermittently saturated in a soft spectral light, the nights in “Atlantics” teem with an aura ripe for the arrival of an apparition of love that’ll breed transformation.

Promoting the film’s theatrical release (prior to its Netflix debut), as well as to campaign since the movie was selected as Senegal’s Oscar entry for Best International Feature Film, Diop sat with RogerEbert.com in Los Angeles for an in-depth dialogue on the decolonization of cinema and language.

As a French person with African roots, what were your first impressions of Senegal as a child? Do you remember the first time you visited?

I don’t have a lot of childhood memories, but I went there with both of my parents and then only with my mother quite regularly as a child, enough to know my Senegalese family well and be close to them, enough to be able to return at the age of 20 after not having gone there for ten years without having the feeling that I was a stranger. The circulation between France and Senegal when I was a kid was quite easy and fluid, even though the environments, cultures, and family landscapes are very different from one country to another. Of course, I have strong sensorial memories. I was very marked and very impressed by so many things in Senegal because it’s a very powerful place.

What are some of those visions or experiences you can recall most vividly?

The omnipresence of certain religious chants really marked me, especially the Sufi chants, that are very present in Dakar. Today I find them extremely sensual and incredibly rich in terms of melody, but as a kid it was a bit scary because they are very haunting, and they just had a very strong impression on me. I remember that I was also very marked by the lighthouse. My aunt used to live in a place where at night the lighthouse would light the whole room where I was sleeping with my cousins. The room would go dark and then the light would come, and then it would go dark again, and so on. That’s one of my most indelible childhood memories, the lighthouse in our bedroom. I was particularly marked by the texture and the atmosphere of the nights in the city and very impressed by the blackness of people’s skin there too.

Now that you mention the lighthouse, the green laser light that washes over the characters at the beachside nightclub resembles a modern lighthouse guiding these spirits back to land.

Yes, the lighthouse is a very important element of “Atlantics” the short that I shot in 2009 and it’s true that in a way the green light calls that to mind. I actually really wanted the lighthouse to be very present in the feature script, a bit like “The Fog” by John Carpenter. In the end we didn’t include it. The way I shot the lighthouse in “Atlantics” the short was so special to me that there was no other way I could film the it other than how it I did it in the short. So we forgot about filming the lighthouse in the feature.

Maybe the way I filmed the light inside the club was a way to make the lighthouse exist in the feature. I have a very physical relationship to things. In the film there’s a circulation between the actors, the lights, and the textures of places. Huge importance is given to objects and visuals. It’s not only about the actors and the story. It’s also through objects, through lights, through sound, through the invisible that the story is being told.

Given your relationship to both France and Senegal, have you ever felt like you exist between two worlds at once? If so, how has that shaped the way you approach storytelling?

It’s a very complex experience to be mixed, to be crossed by different cultures. It’s a really complex subject on its own and a lot of it is expressed in my film. It’s not really that binary. It’s a more fragmented and hybrid landscape. It’s not French or African. It’s more Western versus the rest of the world. It’s hard to talk about it as a subject in general, because it’s quite complex, but I think that the film is really a response to the very fragmented and kaleidoscopic relationship I have to the diversity of my influences, and also the need not to be defined or confined into any category, both aesthetically, cinematographically, or in terms of gender and race. The film is really an invitation to get rid of any categories and it really breaks a lot of molds. As a mixed girl, I’m not white and I’m black, I’m a mix of so many different cultures. I constantly experience the hybridizing of my own complex and mobile identity, which so many people experience—most people do actually.

Prior to this feature you’ve mostly shot your own projects, was it an adjustment to work with a cinematographer for this larger venture? Do you prefer being physically behind the camera?

Some of my shorts I shot on my own. This was the third time I’ve worked with a DP. I thought that the difference between me shooting behind the lens and having a DP was going to be huge and that I was going to feel cut off from something physical in this role. But at the end, my first language is a visual one and deals with framing, so even if there is a DP, I still feel I’m behind the camera. It’s just much more nourished and taken even further because of the dialogue with the DP, because of the fact that I have also more space and energy to give to my actors. Even though I can hear strong propositions from a DP, I still have a very strong relationship to the frame and to what I’m looking for. In the end is not about having the eye behind the camera physically, it’s about the way you look at things overall.

There’s something incredibly interesting about language in “Atlantics,” for the most part people speak Wolof, but for official matters they speak French, and in religious context they use Arabic. This fascinating blend of cultures, of course a vestige of colonialism as well, is very evident through the languages spoken.

That’s how these three cultures meet there. I was very much curious and interested in capturing that through the language and through some situations in which you really experience the different layers of influences from abroad. First there was the arrival of the Arab-Muslim influences, which took place many centuries ago. This is not too far removed from the French colonization period, which we talk about as something very ancient, but it’s not that ancient actually.

The film’s main principle has to do with possession, and at some point when I chose that the spirits were going to come back to possess the girls, when I chose this principle instead of another principle, I thought it was also similar to how other cultures from abroad have possessed Senegal through language and culture.

Senegal was de-possessed from its own culture for so many centuries, and now they’re trying to get back to their own culture. There were also the questions about what the internal dynamics modern cities like Dakar are. What is psyche of a young girl in Dakar today made of? So to me all of these political questions are very stimulating, but the challenge is how can cinema capture that complexity.

In that sense do you feel like the characters you choose to focus on, the genres you mix, and the overall visual language you deploy is a way of decolonize cinema and challenge the way Africa has been portrayed on screen throughout history?

That always crosses my mind and influences the way I am going to approach a scene. It’s both conscious and unconscious, but as a mixed girl, as somebody who has been raised in the Western world and who finally has decided to engage with Africa through film, it’s something that is so part of me. The question of decolonizing the language of cinema, I couldn’t be more concerned by that question. For me, it’s a question that is at the center of every image I create, but not necessarily on a conscious level; it’s just a permanent tension within me. This doesn’t mean that my images are not intuitive and physical, but it’s always a mix of both intuitive approach to image, but fed by that permanent tension caused by a very complex political history. I would say that’s the motor of my cinema. As photography and cinema have been used as propaganda or as a way to misrepresent or to corrupt the image of some territories and their people, cinema can also be used as a way to reconstruct their image, and the identity of these territories and people. It’s like a reconquest.

The Atlantic Ocean is featured prominently as an alluring realm, perhaps a bridge between Africa and the world, perhaps a deathtrap for those who don’t make it out, but also an indomitable force. What’s the significance you wanted to convey about the ocean in how you portray it in the film?

It’s very much directly connected to the geography of the place. The fact that Dakar is surrounded by ocean means there’s a permanent possibility of coming and going, but which also opens and closes, like a trap. It’s a mystical place for Senegalese people, but it’s also in a larger way, a common territory for a global black community. It started with the slave trade and then colonization. The Atlantic Ocean is a very haunted place for the global black community, from the West Indies and the United States to Africa. It’s a very charged place, and that’s why I put an “s” to the title of my film, “Atlantics,” because it was a way to talk about actual migration, but also to touch on other ghost stories through the story of that crossing. The ocean is both political and mythical.

How has the story of “Atlantics” changed in the ten years since you directed the short film version? If it has transformed, was that influenced by something you noticed changed in Senegal or simply based on new interests on your part?

I’ve done several short films and a medium length, but the feature was really evolving in my mind for a long time, ten years. In that time, Senegalese society has changed. One very crucial moment was the Senegalese Spring, which arrived a couple of months after the Arab Spring in 2012, where after 10 years of a very dark period where a lot of young people were escaping the country, where a lot of them died in the ocean, suddenly in 2012, there was a big rupture, with riots, and with a really offensive position of the part of the people against the state. It was quite surprising to see that happen after such a depressive moment.

At that time it really reinforced my intuition that the story of this lost generation should be told by the living one. It had to be told from the point of view or the perspective of the living one. And even before deciding to have the film from the point of view of a woman, I really wanted to make sure that my first feature was dedicated to this lost generation at sea. Still, I didn’t want to enclose the whole youth into that theme because Dakar is comprised of people who live there, who work there, who don’t necessarily want to leave, and who are the lifeline of this place. How do you both honor the memory of a moment of a situation without denying the people who live there and who give life to a city and to a whole country? The answer was in that political moment. Even the element of fire in the film comes from images of the riots. Fire as symbol of life was the motor of the film. In turn, it’s a film about the spring of a person, of a woman, Ada. It’s her blossoming of a woman from teenage to adulthood, from being a child to becoming woman.

Your uncle Djibril Diop Mambéty passed away when you were a teenager, were you familiar with his work at that point? Did his films inspire the inception of your artistic voice or did you only feel influence after he was no longer around?

I was quite young and not really interested in cinema yet when he passed away in 1998. Ten years after his death, in 2008, was when I started to make short films and was definitely getting more into becoming a filmmaker. And ten years after his passing, there were some tributes that were organized for him. I was invited to Senegal with my father, and that was the moment when I realized everything, like how important his legacy and his films were to me and to the world. People come and go, but films remain, which is a fact that we know, but suddenly I really had a much deeper sense of what it means.

I understood then the traces that films are able to leave and the huge importance of film archives, because his films are used by new generations as a starting point to continue the work and the engagement. It sounds a bit revolutionary.

The premature passing of my uncle forced me to position myself even more clearly in terms of which cinema I wanted to defend. As a French woman, I could have decided to shoot films in France, with people of my background there. My first feature was initially supposed to be a quite dark teenage film that happened in France in French and with white people, which wouldn’t have been less me, because it’s also part of me. But the dilemma was about what cinema do I really want to defend today, and what do I think the cinema needs the most, which group of people and which kind of subjects need to be represented the most?

I definitely need this political dimension in my films because making movies is both a luxury and a privilege, but also something that is very challenging and demanding. And for me to be able to put all my life in it, I need there to be a political dimension. Otherwise, it’s not worth it. This doesn’t mean that I’m only going to shoot films in Africa.

You’ve worked consistently as an actress in France and elsewhere, are you able to turn off your director switch off when working on a project as part of the cast, and vice versa, does your background as a performer inform how you direct others?

I leave it behind when it comes to trusting the director and being at his service. I’m really at the service of the film, of the director, and of the character. So in that case, I would say I leave it behind, but I mean, how can I truly leave it behind? I’m a director, but when I’m acting, I’m an actress. It’s like if someone would ask me if I’m white or black. It’s one and same thing. When I direct my actors, I feel so much like an actress because I feel that all my directions come from this “being an actress” place really. And when I’m acting, I think that the fact that I’m also directing nourishes my relationship to acting. It’s one and the same thing.

Fatima Al Qadiri’s score for your film is haunting and intoxicating, it feels like music from everywhere and from nowhere. What were some of the qualities in Al Qadiri’s work that drew you to it and convinced you that her sounds would remarkably complement your images?

I’ve been following Fatima’s work since her very beginnings. I’ve always been extremely inspired, and felt very close to her multicultural and hybrid way of mixing so many different sounds and styles, both very ancient and futuristic, both very Middle East, Arab, mixed with Western sounds, and then mixed with a more electronic style. To me as a mixed girl in the same dynamic, it felt very close to my own personal internal landscape. I’ve listened to all her albums, and I also wrote the script listening to her albums Brute and Desert Strike and at some point I proposed her to do the music because her work is very cinematic and atmospheric. I like the mood of it.

Choosing her was really like casting the actors. I don’t only choose actors, or a DP, or a musician only because of the great results. It’s also because I know that they will have a precise understanding of the political dimension of the film. Fatima comes from the Middle East, and Arab and Muslim culture are very important in Senegal and to the film, also all of the mythology around Djnns is something that Fatima knows by heart. Her music is a Djnn itself. Exactly like with the actors, no other musician could have done what she did for the film.

Being a director it a bit like being a curator, I really choose people for the cast and for the crew because what they do couldn’t be done by somebody else. There’s only a single person who was able to create that music. They also choose me. We choose each other of course. She really reaches incredible dimensions. Since it’s a fantasy film, for me, the music often takes in charge. Fantasy films are mostly sound pieces.

Why did you decide to conclude the film on a striking note about a new future and whom it belongs to?

Something I appreciate a lot in the film of my uncle called “Hyenas” is that the main character became a metaphor for hit own country. That’s similar to what Ada says at the end of the film. She finally emerged from that night and now she’s able to look at herself in the mirror, recognize herself and say, “I am Ada.” She survived loss, which made her more aware of, not only who she is, but that she can stand up after having lost the person she loved the most. Like Senegal, she is taking back control of her destiny.