Maybe it’s because they have to compete against buzzier awards titles, but documentaries at Telluride Film Festival always feel like hidden gems. In this dispatch are two such films, both of which deal with the end of an era. The third film is less accomplished but may find some champions, even if I’m not one of them.

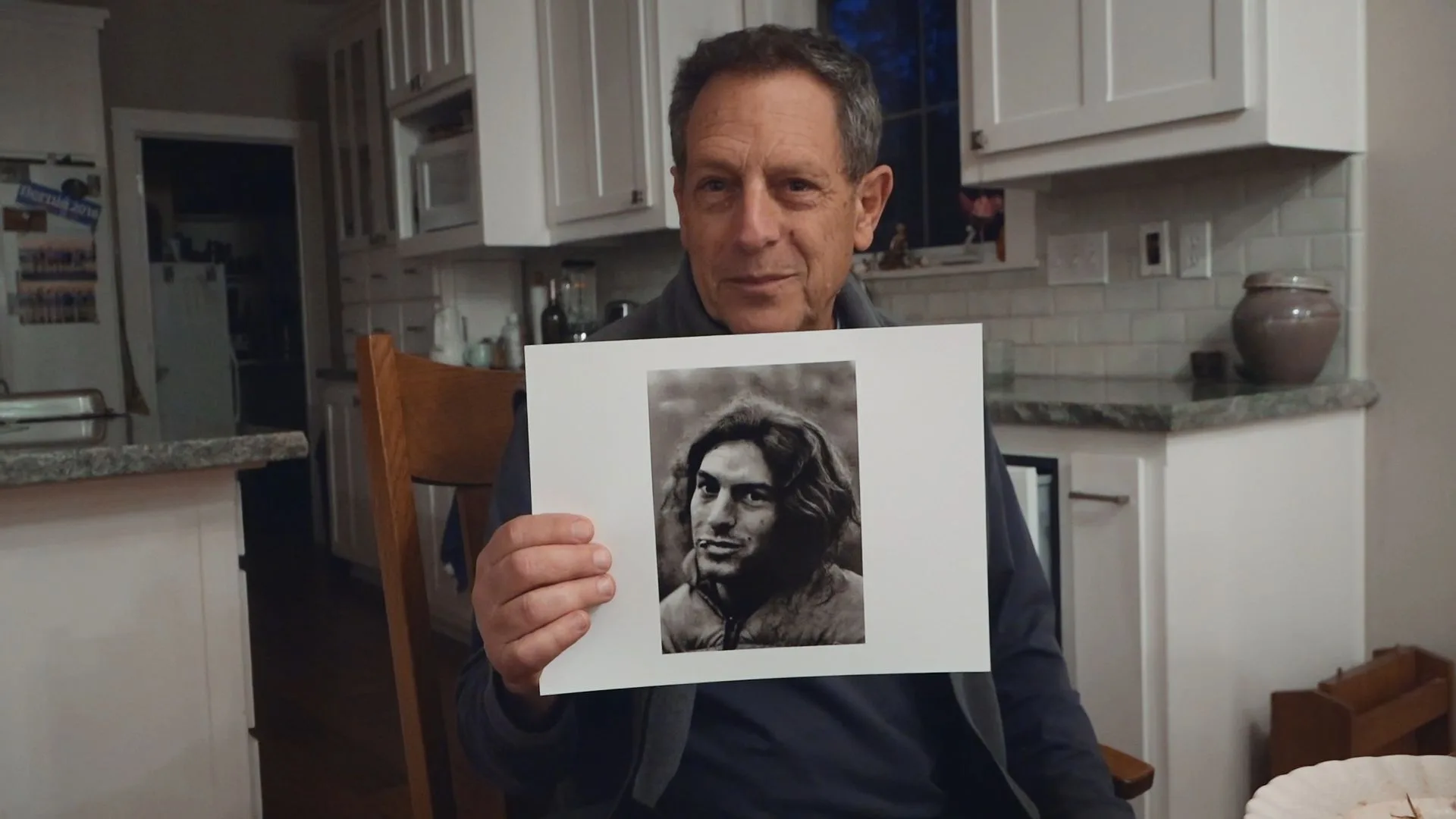

Over twenty years after Robb Moss released “The Same River Twice” (2003)—a documentary that combined footage from his river guiding days with contemporary interviews with his buddies from that time—he returns with new interviews with the same friends who are now living out the winter of their lives. Frank and reflective, “The Bend in the River,” which just welcomed aboard Joel Coen and Francis McDormand as executive producers, is a wistful return by Moss, filled with newer and greater revelations about aging.

Built on some of the footage from “The Same River Twice,” “The Bend in the River,” like waves blending into each other, relies on swift cuts to catch up to Barry, Danny, Cathy and Jeff, and Jim. Barry, for instance, is working to transition into retirement; Danny dedicates herself to her own musical and aerobic passions; Cathy and Jeff live across the street from each other as happily divorced friends; still living in a camper in nature, Jim seems to have changed not at all. Nevertheless, the pleasure of this film is watching these friends watch footage of themselves from twenty years ago and reminisce about the challenges they faced (Barry battling cancer), the mistakes they made (Jeff’s adultery), and their increasing comfort with who they are now (Danny, Cathy, and Jim).

The film also considers how much of the world these friends once knew has deteriorated. “We thought we were immortal and the river was eternal,” says one intertitle. The level of the river they once rafted across has dropped by over fifteen feet in the last twenty years; the forests are scarred by fires.

A less generous viewer might watch “The Bend in the River” and feel jilted by the lack of overtly poetic utterances from these men and women. Barry, in fact, chides Robb Moss that he’s not going to provide such lyricism to the film. However, every observation made by these subjects is quietly poetic. The very act of looking back when there’s not much distance left for looking forward is in itself poignant. But most encouraging is how each one of them is indeed still looking forward. Maybe that’s because they were all river guides. They understand that, like life, you can’t fight the current. All you can do is move to life’s rhythm.

Another movie invested in the passage of time is Mischa Richter’s “Summer Tour.” Produced by Chloe Sevigny, Mickey Liddell, Pete Shilaimon, Evie Kirgan, and Lizzie Nastro, the easygoing documentary follows a group of young Deadheads who are driving across the country to catch every show of Dead & Company’s 2023 goodbye tour. A Deadhead himself, Richter’s film is a thoughtful and loving tribute to an often misunderstood group of fans.

It opens with Jerry, a young man standing in a gas station barefoot, asking for gas for his camper. He is with Annie. Neither of them was alive to witness Jerry Garcia before his death. And yet, they are among the many people their age, such as Trey and Amelia (Annie’s sister), who are dedicated to this band and their music. Some of the cliches about Deadheads hold true for some of the fans, such as the copious use of LSD. Others do not. Many, in fact, do not consume drugs. Most are simply living in community with each other, creating their own markets to sell their talents, spiritually dancing to the music, and playing their instruments.

Richter and his DP Hayden Mason is particularly interested in all the dancing, capturing the free-flowing movement on 16mm with a naturalism that often reminded me of Les Black’s 1967 Los Angeles Easter Sunday Love-In documentary “God Respects Us When We Work, But Loves Us When We Dance.” He witnesses their spinning and twirling in parking lots and in concert venues—which some fans proudly sneak into for free—during the gigs. Richter never films the band performing. But that’s not really the point of “Summer Tour.” This film is for and about the fans.

Nevertheless, that doesn’t mean the music is unimportant. In fact, the structure of the documentary, which has a tendency to rise and fall in tempo and rhythm, sometimes slowing to a meandering crawl, mirrors the wandering soulfulness of the band’s impeccable musicianship and timeless songs. Richter also often uses recordings of fans calling into the Tales from the Golden Road Sirius FM radio programme, wherein fans share what the music means to them. And even as we wind toward the end of the tour, there isn’t sadness or pity. There’s only the excitement of what could be next. One feels the same way about Richter as a filmmaker, whose empathetic eye grants us access to a fascinating subject without ever betraying it.

I have never more fully agreed with a documentary while wishing it dug deeper than Oren Jacoby’s climate change film “This Is Not a Drill.” Written by Betsy West, the film follows several environmental activists across the country as they fight against oil companies. It’s, of course, a more than worthy subject that feels like it’s fighting a battle that’s already passed it by.

The majority of that sentiment arises from the documentary taking place during the Biden administration, which witnessed environmental activists winning some battles against climate change before seemingly losing the entire war with the election of Trump.

“This Is Not a Drill” finds some resonance through its collection of subjects. There’s the Memphis-based Justin P Pearson—who’s now a Tennessee house representative—who experiences a political awakening when he learns that big oil has decided to build a pipeline through the city’s Black neighborhoods because they feel like those enclaves offer “the path of least resistance.” The phrase becomes a rallying cry for the Black residents of Memphis, ushering in a grassroots effort to ward off the pipeline.

Later, we jump to Roishetta Orzane of Lake Charles, Louisiana, who decided to begin her own fight after experiencing multiple climate-change-induced hurricanes. And then there’s Taxes-based blogger Sharon Wilson, who’s using infrared to film the excessive methane output coming from natural gas. Some of these activists we learn are financially backed by the descendants of John D. Rockefeller, the man who made his fortune by drilling, which adds some irony and poignancy to the uprising.

All of these skirmishes, which comprise a larger battle of resistance, are easy to root for, even if you wish the footage captured were less about each person’s personal fight and more about the environmental changes we’re witnessing. It all feels relatively slight and out of step with our grim reality, probably because the administration during the picture’s filming offered some tiny semblance of hope. Instead, “This Is Not a Drill” is a warning that lacks urgency.