Of all the statements I’ve read regarding the COVID-19 pandemic, few have moved me as deeply as the anonymous one recently paraphrased by West Belfast community worker Tommy Holland in a video from Ireland’s Upper Springfield community response team. He said that we shouldn’t view the empty streets out our windows as a sign of the end times, but rather, the “most remarkable act of global solidarity we may ever witness.” We are staying in our homes, first and foremost, to protect those among us—people like my mother with Multiple Sclerosis—who are most susceptible to succumbing to this virus. Communal spaces such as movie theaters may currently be closed across the country, but that won’t stop various major film events from occurring, albeit in a virtual form. The 12th Annual ReelAbilities Film Festival, an essential weeklong marathon in New York City showcasing works of cinema by, about and for people with disabilities, will still run Tuesday, March 31st, through Monday, April 6th, though it will take place entirely online. By having each film available for a 24-hour period from the moment it premieres, while following the scheduled screenings with Q&As, festival director Isaac Zablocki rightly believes that it will advance ReelAbilities’ overarching mission of accessibility.

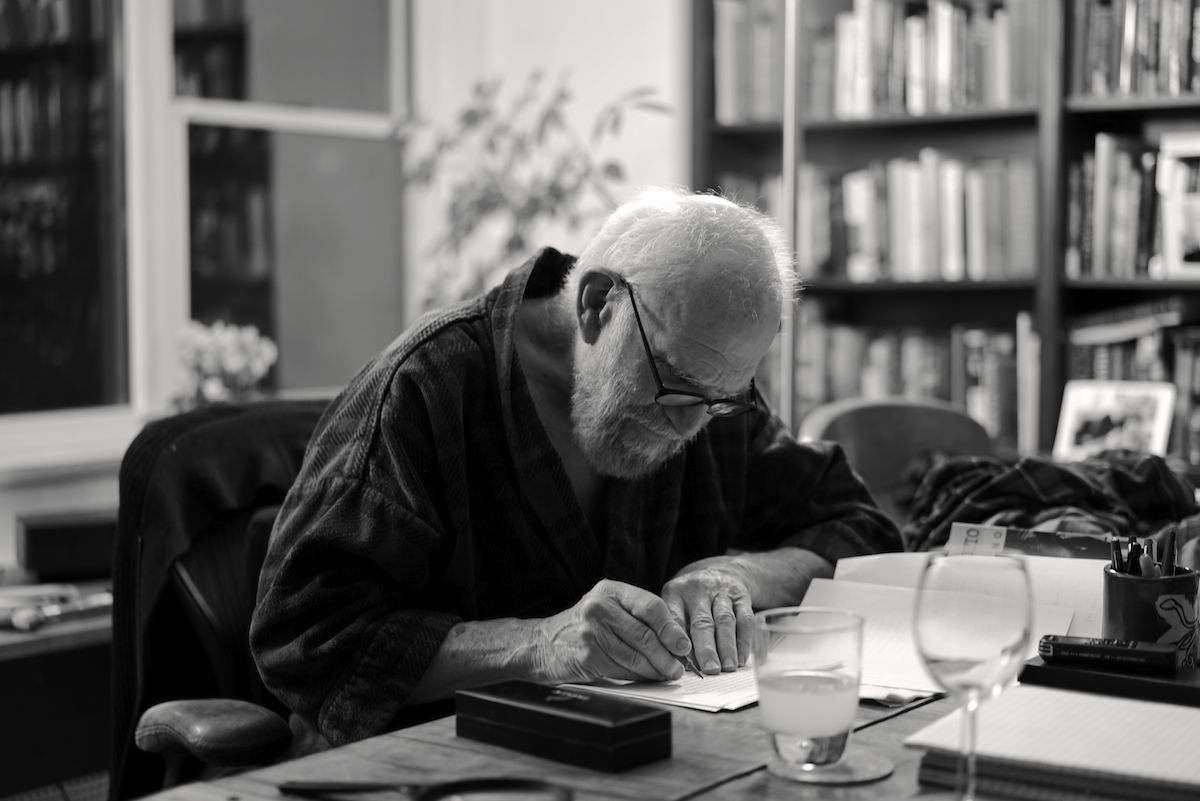

I was fortunate enough to view five of this year’s selections, and one of them instantly ranks among my favorite films I’ve seen in these early, uncertain months of 2020. Ric Burns’ wonderful documentary, “Oliver Sacks: His Own Life,” enables the celebrated neurologist and author to recount his life story in his own words. The footage of Sacks in all his exuberantly and tirelessly inquisitive glory was shot just months before he provided what his close friends believed was a master class in how to bid life adieu. He was diagnosed with metastatic cancer two weeks after he turned in the manuscript of his memoir, which is visualized here with the same level of insight and nuance that Sacks brought to his groundbreaking case studies. His 1973 book Awakenings illuminated the rich inner lives of patients who had been rendered catatonic by the encephalitis lethargica epidemic of the 1920s. After they were treated with L-DOPA, they suddenly became alert and talkative for a period of time, much like how medicinal marijuana temporarily brought movement back to my mother’s limbs. Many neurologists were dismissive of Sacks’ book until it was adapted into Penny Marshall’s well-regarded film nearly two decades later.

Temple Grandin, the brilliant autism spokesperson and professor of animal science, was among the subjects with neurological differences that Sacks profiled, and in Burns’ film, she shoots down claims that he exploited his patients, arguing that he undermined the stereotypes normally attributed to his patients by allowing the reader to walk in their shoes. Sacks’ writing (which I wish was excerpted more here) was similar to great films like Julian Schnabel’s “The Diving Bell and the Butterfly,” which places the audience within the paralyzed body of its protagonist, involving them in his complex and engaging psyche while avoiding any trace of sentiment. After his homosexuality caused his mother to deem him an abomination, prompting him to flee his British home for San Francisco, Sacks knew all too well what it felt like to be marginalized. There’s a lovely denouement to his story, as he finds himself, in his late 70s, falling head over heels for a man, thus breaking his 35-year streak of celibacy. His fascination with neuroscience leads to an especially inspired sequence deconstructing how our eyes process continuous motion, raising provocative questions about the cinematic nature of our vision and how it shapes the flow of time.

“Oliver Sacks: His Own Life” premieres at 7pm on Wednesday, April 1st.

“Honey, you’re changing that boy’s life!” “No, [dramatic pause] he’s changing mine.” Though that cringe-inducing exchange wasn’t from any of the films scathingly analyzed in Salome Chasnoff’s “Code of the Freaks,” it might as well have been. Such dialogue epitomizes Hollywood’s formulaic approach to portraying minorities, whether it be a major league football player in “The Blind Side” (quoted above) or the football coach’s assistant with mental health issues in “Radio” (one of Chasnoff’s primary targets), all of whom are meant to educate the white, able-bodied characters on how to be better people. This picture is a necessary and frequently enraging work of film criticism, as its round-up of impassioned disability experts explain why various critically acclaimed pictures encompassing a century of cinema history fail to reflect the truth of their experience. Aside from Tod Browning’s 1932 “Freaks,” a horror classic in which the audience is made to identify with its ensemble of side show performers, none of the films covered here are upheld as acceptable forms of representation.

One of the strongest insights shared here is how the irreverence of Farrelly Brothers comedies, in which relatable human fallacies are mocked rather than the disability itself, are preferable to dehumanizing inspirational clichés. I’ll freely admit that some of the films ridiculed here are among my personal favorites, such as childhood staples “Heidi” and “The Secret Garden,” both of which are called out for giving disabled viewers false hope that their affliction can be easily remedied. What’s missing here is the full context of these narratives, which are not about miraculous cures but rather insidious manipulation. It doesn’t seem fair to penalize “The Elephant Man” for depicting the historically accurate death of Joseph Merrick, or “Coming Home” for having a romance that is transformative for both partners (and not just due to disability), or even “Million Dollar Baby” for giving its heroine the right to euthanasia. And yet, Chasnoff’s film reminds us that the power of images is undeniable, and the proliferation of negative and misleading ones can have a destructive impact, regardless of their context.

“Code of the Freaks” is premieres at 7pm on Tuesday, March 31st.

As a film geared for families, Serbian director Raško Miljković’s “The Witch Hunters” doesn’t have much of an endearing premise. If anything, it could’ve easily veered into “The Lodge”-level horror, with its pair of 10-year-old friends convinced that the woman one of their fathers has been seeing is a witch, just because she’s an herbalist who does yoga. They plan on defeating her powers not through any supernatural means, but rather, by stabbing her in the neck when she’s asleep. If you can stomach that set-up (and don’t worry, it doesn’t get gory), you’ll be rewarded with a splendid lead performance by Mihajlo Milavic as Jovan, a boy with partial cerebral palsy who isn’t treated as anything other than a normal kid. He’s not written to be an inspirational beacon for his peers, nor is he supposed to teach his pal Milica (an equally impressive Silma Mahmuti)—the one with the allegedly bewitched dad—any profound lessons about the world. In fact, he’s grouchy when she first sits next to him in class, annoyed that a peer has infiltrated his protective bubble.

Simply watching Jovan go about his day reminded me of the horrific bullying endured by kids in his situation, especially during junior high, where raging insecurities give budding adolescents the desperate urge to make others feel small. It’s no surprise that Jovan’s alter ego in escapist fantasies takes the form of a towering superhero with unlimited powers of movement. The best and most wrenching scene in the film occurs when the boy stubbornly ascends a staircase without the help of others, only to collapse back onto the crowd where he quietly weeps, “I want another body.” Though the smile pasted on Milica’s face in the film’s final moments felt patently false, providing too easy a solution for her understandably conflicted emotions, Jovan’s character arc does stick the landing, as he realizes that the world isn’t always as scary as it initially appears to be. The most joyous moment is a small one, as he gains the courage to ask an adult to help him up the stairs of the bus, affirming that there are indeed good souls out there willing to lend a hand.

“The Witch Hunters” premieres at 12pm on Sunday, April 5th.

Having a loved one with a disability entirely alters one’s view of the world. You instantly become more aware of the lingering glances and careless actions made by strangers, the lack of wheelchair ramps in public spaces and the gradual chipping away of one’s dignity when medical professionals utilize patronizing phrases like, “Can we stand?” I nodded in recognition when British actor/drama teacher Sue Wylie included that final observation in the script for her lovely vignette, “Kinetics,” directed by Tom Martin. Wylie based the film on her own semi-autobiographical play, which was based on her experiences of having early-onset Parkinson’s, a diagnosis that she kept secret until she decided to explore it through her cherished art form. As Rose, a character modeled loosely after herself, Wylie is marvelous, tackling her mounting frustrations with a resilient wit, while deftly illustrating the creeping violation of Parkinson’s as it erodes your freedom—the kind most of us take for granted—bit by bit.

I can imagine ReelAbilities audiences cheering the scene where Rose stands up to an impatient man behind her in line at a store, who thinks that the time she takes to pay for her order is indicative of inebriation, an assumption she corrects with a cathartically shaming monologue (I applauded it myself). The heart of the film resides in the bond Rose forges with a student, Lukas (Roly Botha), who battles his ADHD by leaping across rooftops, which he describes as his way of knowing and accepting his limitations while always pushing himself a little further. In part because the film runs only 50 minutes, the melodramatic plot turns that briefly complicate their relationship come off as rushed, though it’s irrefutable that during times of crisis, we do tend to vent at those to whom we are closest. There are perhaps one too many recitations of their favored mantra, “Accept, adapt, adjust,” yet for those battling a disease like Parkinson’s day in and day out, subtlety isn’t always a necessity. I honestly can’t think of a better motto for our species to embrace in this present moment.

“Kinetics” premieres at 6:15pm on Thursday, April 2nd.

A particularly biting observation made in “Code of the Freaks” was how Hollywood narratives often portrayed disabilities as something to be overcome rather than embraced as a strength. Mick Jackson’s astonishing HBO film “Temple Grandin” showed how the autistic mind of its titular subject brought her a perspective of the world that previously hadn’t been documented, as well as an understanding of animals that led to her breaking new ground in the humane treatment of livestock. When I interviewed Grandin in 2015, she was refreshingly blunt in her answers, explaining that she “didn’t give a shit” whether or not it’s legal to put autistic kids in a cash economy, since it may be a better place for them to learn discipline and responsibility. Rachel Wise, one of the employees (dubbed “prospects”) spotlighted in Kaveh Taherian’s hugely uplifting documentary, “25 Prospect Street,” reminded me of Grandin in her brutal honesty as well as her visionary creations, which turn out to be a star attraction at her job.

Prospector Theater in Ridgefield, Connecticut was created by Valerie Jensen as a potentially sustainable business model for employing people with a wide range of abilities, empowering not only their intellect and skills but also their creativity—the kind Oliver Sacks may have been writing about in his final weeks. When Jensen realizes that not enough jobs exist elsewhere for her workers, she simply creates more of them, expanding outside the movie theater with an accompanying restaurant and various landscaping duties. When streaming services threaten to put them out of business, the Prospector decides to up their showmanship, enlisting Wise to draw ingenious flip book-style animations for each release and fellow prospect Daniel to rap about his daily work tasks, while inviting members of the public to submit their own work for a program of superhero-themed short films. Jensen and her team demonstrate how patience, intuition and a willingness to think outside the box are the building blocks toward bringing about a more inclusive world. Since the film, which was made in 2018, has no end coda detailing the fate of the venue, I went on its official site and found that—while it was obviously forced to close due to COVID-19—it had been open to the public for 1,933 consecutive days, ever since it first welcomed customers in November 2014. That in itself is a triumphant achievement, and so is this movie.

“25 Prospect Street” premieres at 1:30pm on Friday, April 3rd.

To find the full line-up of the 12th Annual ReelAbilities Film Festival, running March 31st through April 6th, visit its official site.