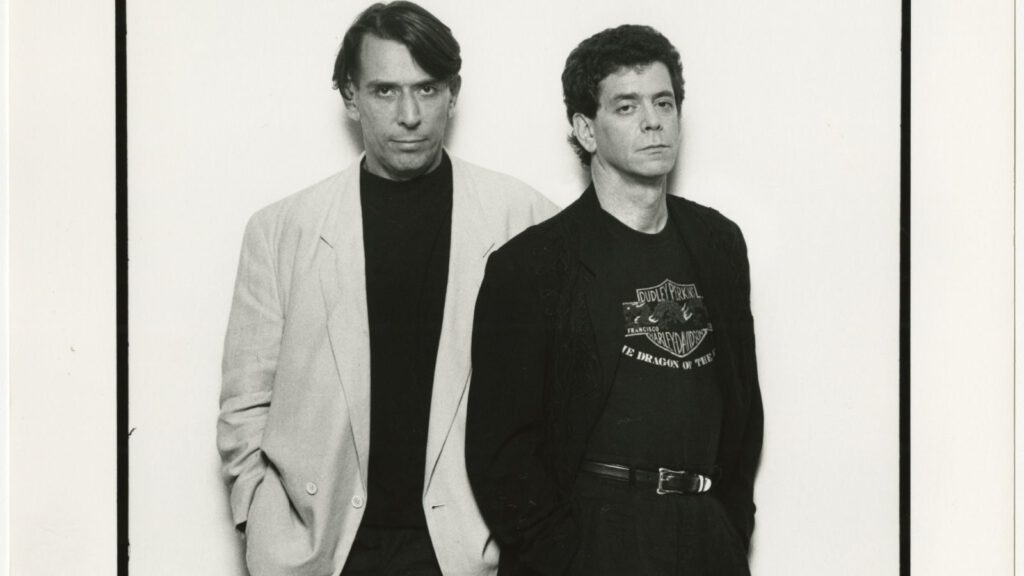

“I think images are worth repeating,” sings Lou Reed halfway through “Songs for Drella.” The film, directed by legendary photographer and regular at the New York Film Festival Ed Lachman, was an account of the concert Reed and fellow former Velvet Underground member John Cale in honor of their departed friend Andy Warhol. It’s playing in the revivals as an answer to the new documentary on the Velvets by Todd Haynes and though I don’t doubt I’ll enjoy the new documentary there’s no way it’s going to match the rawness of Reed and Cale opposite each other, their voices ever so slightly trembling, nothing but their hands on guitars and pianos. How can anything top Cale, doing his best Warhol impression, reading the man’s diary that recounts his afternoons with Cale, doing exercise before his death, their little disagreements, how much they loved each other? The documentary is little but close-ups and the occasional pan, trying to match their stripped-down performance by agreeing on a simple scheme and repeating. Echoes, mirrors, doubles, images worth repeating; it’s what I find every time I look at the movies I have to cover for this festival.

The films I was looking forward to the most were themselves echoes. There was Andrei Ujica’s “2 Pasolini,” which recontextualizes footage that the great Italian director shot while scouting locations for “The Gospel According to St. Matthew.” Hearing the words of the gospel over images of the sea and then ending with a blasphemous rap song seeks to connect the legacy of Marxist filmmakers like Pasolini with a more contemporary form of expression. Ten minutes of bliss. The same impulse guides “Marx Can Wait” by one of my favorite living directors, Marco Bellocchio. Bellocchio’s debut “Fists in the Pocket” had been referenced splendidly in Kira Kovalenko’s “Unclenching the Fist” and it comes back again in Bellocchio’s latest. At 81, it’s not surprising he wants to look back. He gathered his surviving family members for a reunion dinner and while he had them he asked them to reminisce on camera about his twin brother Camillo. Camillo committed suicide in 1968 and the family never quite got over it.

Bellocchio was raised in a stereotypically huge Italian family, and he and his twin were the youngest of a half dozen kids (and more when they moved in with their extended family at the end of the War). Camillo was a nervous kid, the only one who cried at the funeral of their father, and the only one not to find a steady profession, to not have a calling in life. He begged his brothers for work, and they couldn’t help him. He was having romantic woes and his depression and anxiety became unmanageable. When he took his life the family all thought it had to have been an accident. Suicide itself was so taboo in Italy, and they just couldn’t imagine it happening to someone they thought they knew so well. Bellocchio had already turned Camillo’s cloying uncertainty into cinema in the form of the character of the little brother in “Fists,” but he would keep revisiting him. He made a film in 1982 called “The Eyes, The Mouth,” which first featured the last words Camillo said to Marco. The elder twin tried to tell Camillo that it was the state apparatus that was keeping him down, and that was why he couldn’t get a job, and Camillo stopped him in his tracks. He never forgot it. He has Lou Castel, his frequent leading man, recount the story in “The Eyes, The Mouth,” and he tells it again here. Not helping his brother would haunt him and his art.

“I really miss you. I really miss your mind…,” sings Lou Reed. The film would be fairly ordinary, formally speaking, for Bellocchio, but he fills it with exciting music by Ezio Bosso, archival footage, and heartbreaking testimony (his sister Letizia, born without her hearing, is a warm and lovable camera subject; watching her continue to struggle with the idea that Camillo indeed meant take his life is devastating) and so the film transcends the approach. Most films that rely on the footage of great films tend to miss them when they’re not on screen, but not so here. The textural gathering in “Marx Can Wait” is ingratiating and ultimately very emotional. Bellocchio won an honorary Palme d’Or this year at Cannes and at 81 he seems to be just as energized as he was at 29. Bellocchio’s documentaries don’t typically have the legacy of his fiction, but this was a worthy addition to his body of work, one of the most impressive, politically astute, and dynamic from the era of Italian modernism. He’s outlived Fellini, Pasolini, Antonioni, Rosi, and Olmi, and he still has so much to say.

Michelangelo Frammartino seemed once upon a time a shoo-in for canonization among those names, but his infrequent output might keep him from all but the most niche reckonings with the modern cinema. His 2010 film “Le Quattro Volte” was a smash, as much as an art film about time, reincarnation, and goats can be at any rate, but then he waited a full decade to follow it up. “Il Buco” is even better than “Le Quattro Volte,” though destined to be less popular. It’s based on a true story about a spelunking trip to a remote Italian village, but mostly it’s a series of picturesque observations of the invasion of society into a place content to reject it. The cave dwellers make for fascinating spectacle; men lighting small fires and letting them drift hundreds of feet into nothingness to gauge the death of the cave system. Outside men tend their farm animals, watch one communal television, and die of natural causes. The further into the earth we go, the more we miss of life above. Which men have it right?

Mamoru Hosoda’s rapturously animated “Belle” is interested in the same question. Its characters are headed into a different kind of cave, a place of pure fantasy and dissociation. A young girl enters a living social network and becomes a sensation after she entertains dozens then hundreds then millions with her singing voice. She forgot how to sing in the real world after her mother died saving another little girl from drowning when she was young. She and her father have since grown distant, and she’s become a pariah at school. When she becomes Belle online, she forgets all of that, indeed forgets all of her own trouble. She sees a figure on the online world, a kind of creature, part-man, part-dragon, and she makes it her mission to help him, which involves reckoning with the real world for the first time since she was a child.

“Belle” is stupendous work, a movie with old preoccupations (new bodies, false worlds, beauty shining light on decaying personae) but a sparkling new vision for them. I was routinely rendered slack jawed in wonder at the sight of phantom whales carrying Belle to heavenly highs, and of families finding the language to reconcile. It reminded me of another film in the festival, one of my favorites, Allison Chhorn’s “Blind Body.” It’s interested in refiguring the things we know and understand—family, sight, sound, grief, the speed of our thoughts. “Blind Body” is as small as “Belle” is huge and expansive, but perhaps even more affecting. Chhorn’s documentary work is marvelous, and “Blind Body” brings us uncomfortably close to the elderly flesh and warped vision of an old family member, finding exciting visual language to describe what we all know in our hearts: that losing what we knew all of our lives is terrifying and lonely. This is a profound act of empathy in the form of winsome abstraction, and I was similarly moved beyond words.

I saw in this little study the aging Bellocchio siblings, Lou Reed and John Cale looking back on their lost comrade, and the roaring ocean of Pasolini. I think images are worth repeating when they’re as good as these.