Two films in the NYFF Spotlight on Documentary sidebar offer detailed observations of writer Joan Didion and playwright Arthur Miller, respectively. Both are directed by family members: Didion speaks to her nephew, actor Griffin Dunne in real time in “Joan Didion: The Center Will Not Hold” while Miller exists primarily in a series of well-executed home movies shot by his filmmaker daughter, Rebecca, in “Arthur Miller: Writer.” Fans of either subject will find much to ponder about the craft of writing and the trials and tribulations of lives well-lived.

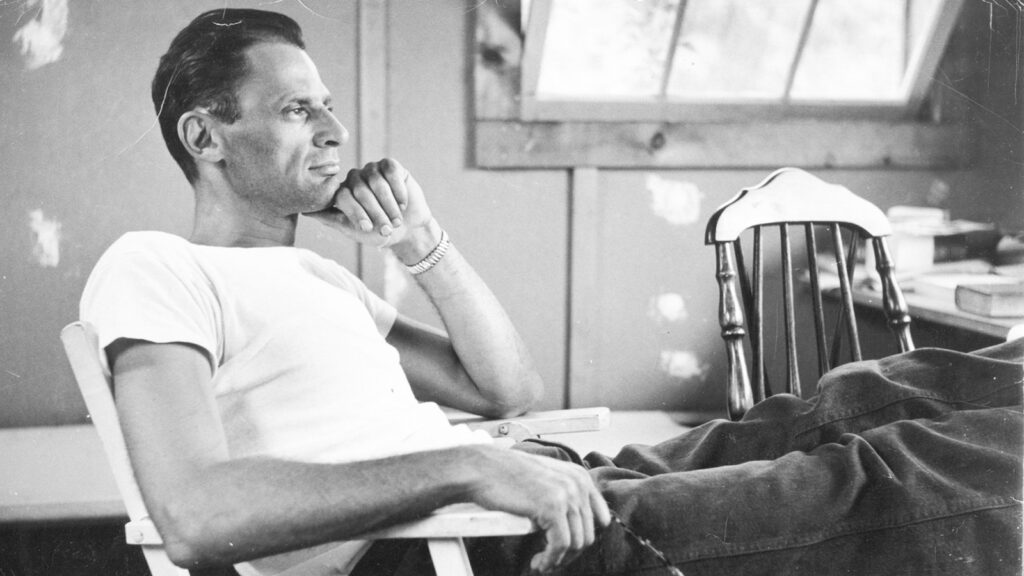

The better of the two documentaries, “Arthur Miller: Writer” is elevated by the nature of its construction. Even in the earliest movies, Rebecca Miller has an eye for composition. Her interviews, mostly conducted at her father’s house, have an easy-going, unguarded feeling. It’s as if the viewer were sitting at the feet of a master listening to his ruminations on a variety of topics, including his own works.

Miller led a fascinating life, which included being married to Marilyn Monroe (for whom he penned one of her best roles in “The Misfits”) and a stint on the HUAC blacklist. Surprisingly, his blacklisting came after the release of his famous, thinly-veiled play on the subject, “The Crucible.” After Miller’s longtime friend, Elia Kazan named names, Miller went to Salem to research the witch trials that would form the basis of “The Crucible.” “Arthur Miller: Writer” delves into the real-life circumstances surrounding this play and also answers several questions about Miller’s most famous character, “Death of a Salesman”’s Willy Loman.

If this description is giving you nightmarish flashbacks to your high school English class (and I admit no love for “Salesman,” a play I hated reading in 11th grade), don’t be deterred. In addition to providing information on all of his successful and not so successful plays, “Arthur Miller: Writer” expands focus to give a bigger picture of what was happening in America, and how Miller shaped that into his art. It also shows how that art may have shaped his audience’s perception of America.

Through it all, we have Miller’s voice and his wisdom, which he dispenses to his daughter while doing mundane things like tooling around in his wood shop. He talks about his family, including a mother who saw portents, about growing up Jewish and the audience response to “All My Sons” and “A View from the Bridge.” Rebecca Miller also chimes in with her own observations, but her father remains front and center in this informative documentary.

Though shorter by about 12 minutes, “Joan Didion: The Center Will Not Hold” felt like the longer, less enjoyable film for me. By the time of this screening, I had been suffering from Talking Head Documentary Fatigue, so I blame myself for not being as invested as I was in other documentaries. I found this film to ultimately be visually exhausting. However, what vaulted this into the favorable column for me was the undeniable, sometimes shocking honesty of its subject; some of the things I’d heard here would not leave me alone for days.

Didion is an eccentric character. In many of her later interviews, she talks with her hands, using them for visual punctuation and emphasis (it’s actually quite distracting, even to a fellow hands-talker like myself). She takes the same laser-like focus to her own personal life as she did to her journalistic subjects. And she was an unsparing journalist. She dissects the hills and valleys of her life with clinical precision, and we see how her life influenced her work. “You use what you have,” she tells us at one point, “and that is what I had at the moment.”

“Joan Didion: The Center Will Not Hold” also discusses Didion’s marriage to Griffin Dunne’s uncle, John Gregory Dunne, the man who was at times her writing partner and harshest editor. The couple edited each other’s work, even as their marriage was dissolving, and their mutual respect for one another seems rooted in sharing the literary battle scars understood only by those who write. Whether it’s hearing Didion read from her own material, or seeing Vanessa Redgrave interpret Didion’s book The Year of Magical Thinking onstage, Joan Didion remains the center of this documentary. Unlike the center in the title, she holds quite well.

When Jeanne (Esther Garrel) shows up unannounced and in despair at her father’s door in “Lover for a Day,” she finds that he is not alone. That her divorced father, Gilles (Eric Caravaca) has a lover does not bother her, nor is she remotely shocked that the lover in question, Ariane (Louise Chevillotte), is Jeanne’s age. We’re not surprised either, as we’ve witnessed Ariane in a pre-credits sex scene with Gilles, who is also her philosophy teacher. Within this framework, director Philippe Garrel continues his cinematic discussion about love, fidelity and being true to oneself. As usual, he casts a family member as an onscreen accomplice, though this time he handles his meditations in an unusually short (for him, that is) 74-minutes.

The press notes call this a platonic ménage-a-trois, but “Lover for A Day” plays more like a slightly off-kilter family drama, with Ariane cast as a stepmother-like figure for Jeanne. This comes into focus most clearly after Jeanne, distraught from the romantic break-up that sent her running home to Papa, attempts suicide only to be saved by Ariane. Ariane keeps Jeanne’s secret, and the two bond and begin to hang out together. Meanwhile, Gilles retreats into the background, which is a good thing because his love affair is the least interesting aspect of the plot. Movies about raggedy old guys banging attractive younger women are as played out as Kwame’s Polka-Dots, so the Jeanne-Ariane subplot is a most welcome addition.

There’s a lot of talk about “fidelity” in this movie. There’s even an omniscient female voice narrating the film that may be fidelity incarnate. But “Lover for A Day” has an odd double-standard about what constitutes forgivable indiscretion; Gilles slaps Ariane for her dalliances yet his own get a pass. Garrel and his screenwriter, the legendary Jean-Claude Carriere manage to cram a lot of philosophical ideas and concepts into the short running time, but I found myself caring less about them and just allowing the film’s harsh black and white cinematography to wash over me as I rooted for Ariane to get her life back together.