For a movie like “The Man Who Killed Hitler and Then The Bigfoot,” it all starts with the title. You think you know what you’re going to get, and for the most part you’d be right—Sam Elliott does play a man who, a long time ago, killed Hitler. And later in the movie, he does kill Bigfoot. But just as this movie starts with an ooh-rah, pulpy promise, the story from writer/director Robert Krzykowski proves to have an unassuming, profound beauty. Like Clint Eastwood’s revisionist Western “Unforgiven,” the title is revealed to not be a heroic statement, but a curse.

A wise, odd, and unforgettable ballad, “The Man Who Killed Hitler and Then The Bigfoot” is one that does better with contemplation once you part ways with expectation. If you go to the film wanting to high-five a movie that promises Elliott as a bad-ass, you will be disappointed. Krzykowski knows that a film focused on violence truly resonates when the scenes between the action are even more memorable. In the case here, this movie has some heavily dialogue-driven passages that ponder the alternating luck and curses he has experienced in his life, like with a European man during a close shave before Calvin’s assassination mission, or with a recently found 20-dollar bill, handing it over to a convenience store clerk played by Ellar Coltrane of “Boyhood.”

Krzykowski presents Barr’s flashbacks of killing Hitler and being in war time with great detail in pacing and production design, their dreaminess enhanced by Joe Kraemer’s traditional orchestral score. Just as much, as an editor, Krzykowski is on occasion precious with this time, showing these parts of his life in scenes that might feel bloated. But when it comes to Calvin’s present, Krzykowski is wonderfully not precious, like when he jumps right in the middle of Barr’s hunt for Bigfoot, which is contrived in the best sci-fi fashion. Not a spoiler, the second half of the film does not climax with Calvin killing Bigfoot. The movie has so much more on its mind.

But these scenes are just verses, and ruminations, to the chorus the film always brings us back to: Barr, old and alone, with his dog. His title legacy does not offer him a type of honor as he sits in his house, but isolates him even from his brother Ed (Larry Miller), one of the few lifelines he had when Calvin had to change his name after the mission. And in what might be the most classic of its touches, a woman that he loved before all of this has vanished. “The Man Who Killed Hitler and Then The Bigfoot” is a movie of an old soul, one that’s wise beyond its decades just like Andrew Haigh’s “45 Years.” The film is more powerful than viewers of either high or lowbrow desires could desire, and it fashions a haunting tone out of its premise. Like Calvin, it has extremely complicated, heartbreaking notions of legacy, of becoming a symbol, of seeing other people as being worthy of violence or not.

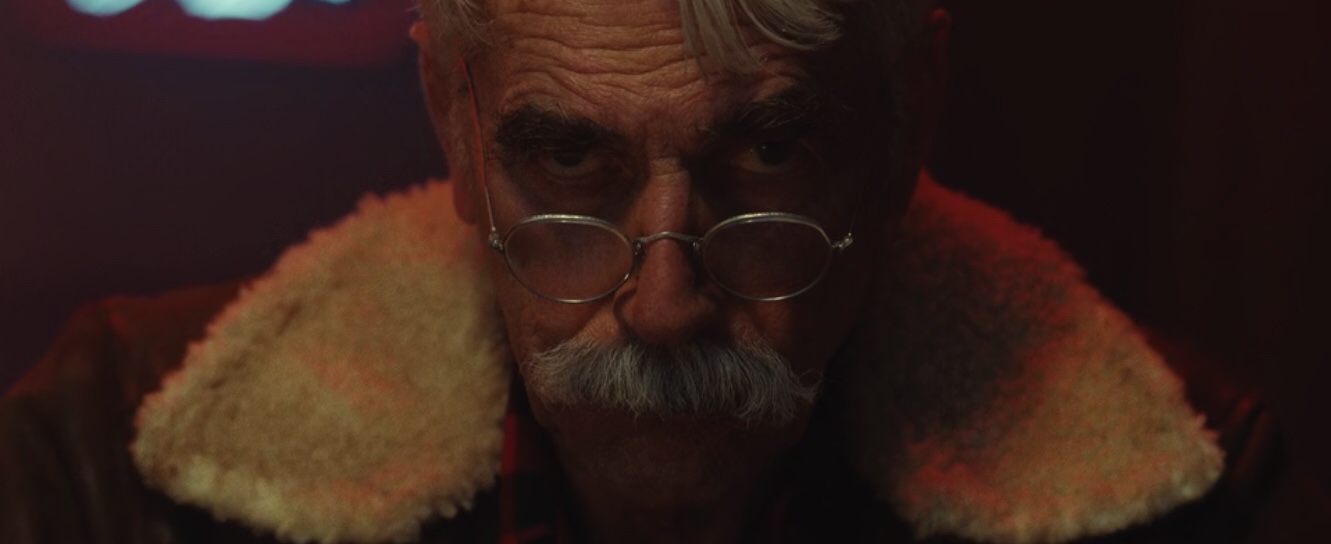

More than its title kills, the film’s most captivating passage is a showcase of Elliott’s incredible way with pacing his words so that each of his thoughts land. As he speaks in an extended close-up to two men who want to hire him for the Bigfoot assassination, a quiet living room conversation yields a walloping power. “It’s nothing like the comic book you want it to be,” Elliott says in the middle of the tale, his matter-of-fact gaze desperately wanting to caution against hagiography. And he’s right. Krzykowski’s exquisite “The Man Who Killed Hitler and Then The Bigfoot” is even better.

One segment of Fantasia that I was told by local Montreal writer (and RogerEbert.com contributor) Justine Smith to keep a close eye on was their Camera Lucida program. With titles this year like Josephine Decker’s “Madeline’s Madeline” and Nicolas Pesce’s “Piercing,” it has the general air of slightly experimental projects that speak to a director’s talents as much as the film itself. I imagine a mascot for this section must be “Luz,” a directorial debut from Tilman Singer that had its North American premiere at Fantasia. It’s not the first horror movie to lean on a more classic horror style (given the grain of its Kodak 16mm despite being shown on DCP, and its creepy, synth-heavy score), but rarely have movies built from that ’80s vibe felt so innovative.

It’s no fun to describe “Luz” narratively, in part because its story isn’t entirely there. But it’s much more fun to recall just a couple of its gorgeous images: a woman at an empty bar, telling a bizarre story to a psychotherapist about a former classmate and a demon in their school; seeing said former classmate as a taxi cab driver, reenact a tale of demonic possession in front of previous psychotherapist as if it were an improv piece. Juxtaposing extensive, slow-zooming takes with a story that has truly unpredictable impulses, it’s a hypnotic offering of horror film atmosphere. The settings are bizarrely empty, the actors are blocked as if they were art installations, and every visual component feels like an intentional ingredient. You trust Singer almost immediately that he knows what he’s doing, and you follow his massive vision through its many bizarre segments to the very end.

“Luz” is the best kind of calling card project, and that is not a slight. It’s barely a feature by standards of running time (70 minutes) and there isn’t enough substantive narrative tissue to make an even bigger impact. But it’s comprised of numerous searing images, the immediate result of Singer’s thrilling precision with all aspects across the board. After “Luz” is over, you just know that Singer is bound to make a great movie soon.

Among the handful of Fantasia world premieres for movies you should definitely be on the lookout for, there’s “Cam,” a character-driven horror piece that focuses on the existential crisis of cam girl Lola (whose real name is Alice, and is played dexterously by Madeline Brewer), which initially starts when she is locked out of her video-broadcast account. But things become super weird when someone who is not her but looks exactly like her starts broadcasting under that same account. And to her complete horror, but also the joy of her rabid fans, this other version of Lola goes beyond the rules she previously set for herself (such as no nudity), feeding into their desire to control both the real and fake Alice.

Written by Isa Mazzei (from a story by Mazzei, director Daniel Goldhaber and Isabelle Link-Levy), it all very much has the air of a feature-length “Black Mirror” episode, which speaks to its quality, but also to its limitations. “Cam” is a gripping nightmare inspired by something not so much as incomprehensible but quietly disturbing, bringing a lot of questions into fray: her loss of agency, the insatiable appetite for viewers who are objectifying the cam girl they’re constantly given tokens to, and the extent to which men will not listen to women when they need help. Cinematographer Katelin Arizmendi provides a sobering look at the business, the bright-colored fantasy nature of a cam girl’s workplace sharply juxtaposed with the stark daylight of the truly weird goings-on.

But like how “Black Mirror” episodes can sometimes focus on one idea with a few discussion topics along the way, so does “Cam” feel a bit thin with its story. It makes for repeated beats, like when Alice is constantly disturbed by the image of her that others are seeing, while people don’t believe her. It’s the character development in this case that makes the story’s turn of events most intriguing, as we see different shades of men who choose what they want to believe about what she has to say, while not having their own boundaries when interacting with her as Alice, not Lola.

Still, the short is an excellent showcase for Brewer, who carries this movie through so many tense passages and helps viewers immediately recognize the complicated human behind the camera, and Goldhaber, who grabs a sturdy pitch and runs with the horror of it. The ending feels like a bit of a cop-out, even with all of the existential questions floating around its story. But it’s a fitfully bizarre journey up to that point, while offering a nuanced and heartfelt portrayal of solo workers in the sex industry.