Friday’s second film, “L’Inhumaine,” was like an adrenaline shot of what Richard Neupert called “pure cinema,” as set to the tune of a wild arrangement of the Alloy Orchestra. The film was directed by Marcel L’Herbier, a famous French poet who discovered the power of cinema and how it could, as Neupert called it, “make us think differently.” The first of two silent films to play the fest, “L’Inhumaine” captivated the Ebertfest audience with a wonderful presentation of sight and sound, a film that was defined previously as a “grandiose symphony in color” or a cinematic experience. The film was introduced with contagious enthusiasm from the highly knowledgeable Neupert, a film professor at the University of Georgia.

The craziness of the story begins with plot, which is not unlike an episode of ABC’s “The Bachelorette” on cocaine: A group of pasty middle-aged men (even the one playing a maharajah, in dark make-up) try to woo an equally vain socialite and singer named Claire, whose close-ups are with angelic lighting and soft focus, her head always tilted back. One of the suitors shows up late to the party, but steals her away to tell her that if she doesn’t love him that he’ll kill himself. She is not impressed or worried about this in the slightest, so he goes and does just that. His death creates a scandal across the city that lingers over her concert performance the next night, but the turn of events are even more surprising, when Einar shows up back from the dead, and becomes a mad scientist.

“L’Inhumaine” gets a great energy from its seething contempt towards people like Claire, who has her servants wear masks of smiling faces. No one is particularly likable, but the angst makes the story fascinating on its own level, especially as it seems to have no standards. When it reaches an ultimately romantic end (or so it thinks), it feels instead more like a complete farce about humanity, instead of a wayward way of embracing it. Though the movie is not a comedy, nor is its crazy filmmaking anything to laugh at, it has the wackiness of a very strong farce. It is a heavenly piece of mad cinema, if such a sub genre existed before or after “L’Inhumaine.”

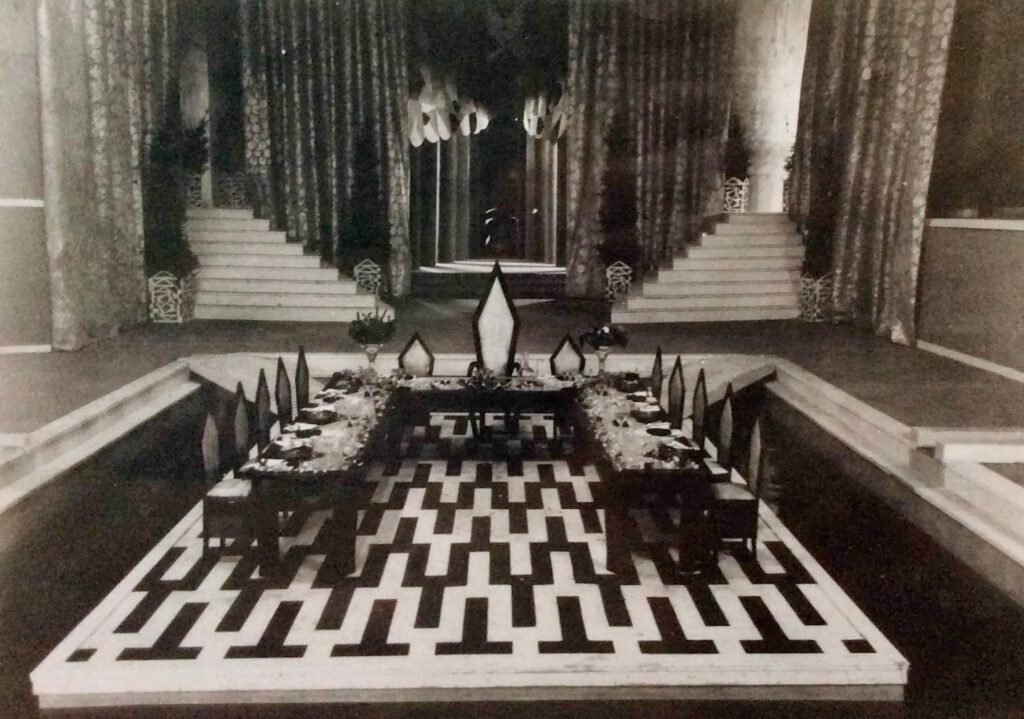

But this all adds to the lunacy of a film that transcends any mere standard with such bold filmmaking even by today’s standards, including an aggressive color palette (red and green tints, not just blue or yellow), and extremely diverse editing techniques, which at one point reaches the speed of strobe lighting during the mad scientist segment. Its production design has a similarly extreme flair with massive sets, some directly influenced by the shapes, contours and randomness of Cubism. (The picture above gives you just one idea of the jagged, long, expansive pieces of this amazing puzzle.) The film had a reported three production designers, and it plays out like three different movies.

For someone who hadn’t seen it before, “L’Inhumaine” was alive in its presentation, with this score providing an entire physical presence, like the difference between meeting a person in real life as opposed to just hearing about them. Using a variety of instruments ranging from a saw, fuzz guitar, synth, and all of the various chimes and percussive instruments in between, the impressionism of L’Herbier’s images took on their own intensity with the score. For such a bizarre story, their score went underneath the content, playing far more to the warped perspective of the tale then treating it with coating on top as with so many silent film scores on DVDs.

The film was engaged by a Q&A afterward featuring members of the Alloy Orchestra and Neupert—considering their background and knowledge they must have seen the movie a collective hundred times. They were joined by Sony Pictures Classics co-president and co-founder Michael Barker, who said that this was “the best film with the worst acting.”

Along with history about the production and L’Herbier, there was a discussion about the history of the Alloy Orchestra. “When we started [scoring], people thought we were making fun of movies,” equating their initial response to something like “Mystery Science Theater 3000.” They shared their process, in that they don’t study the music before scoring films, and try to come up with as many sounds as they can.

Roger once defined them as “classical music with a rock attitude.” One of the members added to that, “but with the freedom of jazz.”