Day two of Ebertfest 2016 opened with a pair of panels that

exemplify the festival’s approach to the arts. For Ebertfest, as for Roger

Ebert when he wrote about film, movies don’t get exist in a vacuum. And so

programming a film like “Love & Mercy” leads to a panel about “Challenging

Stigma Through Love, Mercy and the Arts,” followed by a different group of

filmmakers and critics discussing “Creating Empathy on the Big Screen.” Both

panels inspire festgoers to look at not just the films of this year’s

event but the cinema they see throughout the year from a different angle. How

are filmmakers addressing issues like mental illness? How are they representing

empathy, kindness, and compassion in their filmmaking? And how do they work to

produce empathy as described in one of Roger’s most notable quotes: “For me,

the movies are like a machine that generates empathy. It lets you understand

hopes, aspirations, dreams and fears. It helps us to identify with the people

that are sharing this journey with us.”

It’s impossible not to take the tone of that concept through

the rest of the day, which included screenings of Paul Weitz’s “Grandma,”

Michael Polish’s “Northfork” and Carol Reed’s “The Third Man.” Part of the

concept of empathy which we discussed in the morning (I sat on the panel with

Guillermo Del Toro, Paul Cox, Michael Polish, Paul Weitz, and others) is the idea

that film is transportive—we go to places we wouldn’t otherwise go and see

lives we wouldn’t otherwise see. The sense of a cinematic journey was evident

in today’s trio of films, taking us from present day L.A. to a 1950s Montana

that feels even more displaced from time to a major European city ravaged by

World War II. On paper, the trio seems to have nothing in common, but Ebertfest

engenders a sense of community so strong that all cinema falls underneath one

umbrella. It is all a journey. It is all empathetic. It is all essential.

After the panels, the day’s film program started with a

lively, engaged audience willing to go on the journey with Elle (Lily Tomlin)

and her granddaughter Sage (Julia Garner) in Paul Weitz’s nuanced “Grandma.” Seeing

it again on the larger-than-imaginable Virginia Theatre screen in

Champaign-Urbana, I was struck by the easy, uncomplicated flow of the 79-minute

film, and Weitz detailed in his Q&A after the screening (with producer

Andrew Miano guesting as well) that the first thing they cut in the editing

process was anything that felt too much like it was a going for a laugh. There’s

no desperation in “Grandma”; no eagerness to please; no political statement to

make. It is a character study of two women at very different turning points in their

life, and an insightful example of how those moments never stop coming whether

one is a teenage girl needing an abortion or her grandmother needed to write

another chapter in how she’s dealing with grief.

Weitz spoke at length about how much of the process of “Grandma”

he handed over to his actors, especially Tomlin, whom he basically allowed to

guide the production in a way that made the film feel both her own and honest.

He went as far as to say sometimes that his role as a director is more similar to

the Hippocratic Oath—“Do No Harm” and just let things happen—especially in the

already-famous mini-movie-within-a-movie co-starring Sam EIliott, which he

compared to a Harold Pinter play. So much of how that scene unfolded was

serendipitous, almost coming organically on the set, and Weitz claimed it was

just about being in the right shot while it was unfolding.

Near the end of Weitz’s Q&A, he spoke about how much of

the film is about grief—how do you get past loss? Of course, grief and loss are

elements of Michael Polish’s “Northfork” as well, even though the film (which

was shown in a glorious 35MM print) couldn’t really be much more different on

paper. And yet listening to Willis (Mark Polish) and his father (James Woods) discuss whether or not to excavate the body of his mother, I was struck by the unexpected

dilemma that initiates “Grandma.” Life (and even death) often doesn’t work out as planned. And

film makes us empathetic to that fact. We all deal with the unexpected.

Seeing “Northfork” for the first time over a decade, I was

struck by the film’s ambition. Even in today’s cinema in which Malick clones

are more common, it feels distinctive, a fact enhanced by a unique look that

even Polish admitted makes it look much older than 13 years. It is a film that

Roger argued owes a debt to Terence Malick—and the vistas recall “Days of

Heaven”—but it is also a deeply personal film for Polish, who told Matt Zoller

Seitz in a Q&A that it was the first script he wrote with his brother, and

the project was designed and put together by family members. His father built

most of the sets in the harsh Montana landscape that Polish remembered from his

youth (and still calls home). The story of a small town being evacuated so it

can be flooded to create a lake has a fascinating air of the inevitable. Roger

said in a clip that played before it that the waters are rising for us all, and

there’s something fascinatingly relatable about this world that is technically

so alien from us all, which is the key to empathy. We may not be evacuating our

homes, but the march of time always stops for massive changes and “Northfork”

captures something intrinsic about how we leave parts of our lives behind—or even

this world behind when we die. It is about transition, something we will all

experience in several forms over the course of our lives, and it is as

ambitious a film as is contained in this year’s entire program.

Polish also spoke personally about Roger’s impact on him,

telling a great story about how hard it was to concentrate on the day he knew

that Roger was watching his debut, “Twin Falls, Idaho.” While his father tried

to get him to go to Home Depot and continue “sweating pipes” (they were working

on a house), Polish couldn’t concentrate, even hearing the fax machine with the

notes about Ebert’s opinion on the film spitting out as he was working

underneath his house. He introduced the film with a similar anecdote about when

“Northfork” premiered at Sundance. The admittedly slow film was met with

silence when it ended, and Polish said that Roger came down the aisle, looked

at him and said they were going to breakfast the next day. Whether he liked or

hated his films, Roger inspired Michael to “just keep filming.” The work is

what matters.

There’s no work quite like Carol Reed’s “The Third Man,”

presented last night in a glorious 4K restoration that made it feel somehow new despite having

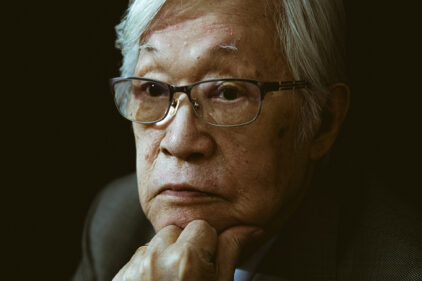

seen it multiple times. Accompanying the film to Ebertfest was Angela Allen, a

script supervisor on the movie, who went on to work for decades in cinema,

including collaborating on every John Huston film. Only 19 on the set of “The

Third Man,” the now-86-year-old told amazing stories after the screening in a

Q&A moderated by Michael Phillips and Nate Kohn. Essentially, “The Third

Man” is a film birthed from Reed’s unbelievable talent, but also from a time

and place that couldn’t be replicated. It would be impossible to remake the

film because one couldn’t capture Vienna right after World War II, which is a

character in the film. Even the notable zither score, which Phillips told the

audience was actually #1 on the hit parade for 11 weeks, was almost accidental,

as Reed stumbled upon the zither player in a café. Kohn commented that when he

lived in London and Paris, several people claimed they took Carol Reed to that café

to hear the zither.

Before that Q&A, “The Third Man” entranced its audience

as it does every time its screens. One of Roger’s top ten films of all time,

Reed’s thriller still has an amazing power to capture viewers, keeping them as

on their toes as its protagonist, the confused Holly Martins (Joseph Cotton), a

man immediately thrown off his axis (as represented by the film’s daring

angles) when he arrives, finds himself in a world he doesn’t understand. His

friend, Harry Lime (Orson Welles) was killed in an accident just before he

arrived. Or was he? “The Third Man” is a great example of how a film can

replicate its central character’s sense of confusion. He is constantly yelled

at in a language he doesn’t understand (and isn’t subtitled) and even simple

conversations are filmed at canted angles, designed to show a world askew. And

then there’s the imagery. The final act of “The Third Man” contains some of my

favorite visuals of all time, from Holly’s meeting with Harry (and it’s world

spinning outside) to the shadows in the sewers to one of my favorite endings of

all time.

Allen spoke about that ending, noting that they reshot it

several times and Reed asked Alida Valli to start her walk further back every

time, going with the final take and the longest walk. She also told amazing

stories about Orson Welles, adamantly denying his claims that he actually

directed the film. From the sound of it, he was more difficult than involved.

On the first day in Vienna, he went down to the sewers to find the crew eating

bacon sandwiches in the unhygienic shooting location. He was so disgusted that

he refused to go down there again, meaning that a lot of the shots in the

climax of “The Third Man” are not actually Welles, and the ones that do contain

him were done on a set in London.

Before “The Third Man,” Chaz and Michael Phillips introduced

the Ebert Fellows, students writing about Ebertfest, and it was a great

inclusion on the first full day. Everything comes full circle. From a 1949

thriller to a 2015 dramedy; from Roger’s writing to a new generation. The

journey never stops.