“When I peruse myself in the looking glass, what I see is a gargoyle”, says William Turner (Timothy Spall) to Mrs. Booth (Marion Bailey), the proprietor of a guest room the great British painter frequents on his inspirational trips to the countryside. He has just declared the stately, freshly widowed hostess “a woman of profound beauty”—and even though none of them resembles a typical meet-cute material, what goes on is unmistakably a flirtation. The burly, hirsute, borderline inarticulate lump of a man is breaking through a wall of solitude that the movie is careful and deeply humane in depicting.

Mike Leigh’s “Mr. Turner,” which opened this year’s Cannes Main Competition in a grand, promising manner, is one of the strangest biopics imaginable: a private, nearly plotless take on the life of a man whose passions were all intensely inward. Turner’s paintings, most of which depict unpopulated landscapes as inchoate swirls of mist, color and texture, feel deeply modern even today. The movie is partly about the alienation of an artist working ahead of his time and against the grain of what is deemed aesthetically acceptable (it’s a portrait of a proto-impressionst and a proto-Pollock, spewing spit and yolk onto his canvas as if to make his work his progeny).

This incongruity with an artist’s own era is not the film’s main theme, however. “Mr. Turner” is far from the pop-mythology of Vincente Minnelli’s “Lust for Life” and closer to the open-ended approach of Robert Altman’s “Vincent & Theo,” with Leigh focusing more on his subject’s daily routine and dynamics of his temperament than on any clear-cut narrative arc. Spall’s stellar performance, in which every growl seems fine-tuned, is a strong anchor for a film that’s otherwise all throwaway scenes, slight details and arresting cameos. We get to know women in Turner’s life—some abused, some abandoned, some idolized and cherished—but what the film suggests is that real human connection is an elusive thing for a genius in any era. When Turner sings a Henry Purcell song to impress a young girl, he sounds like a failed Tom Waits; he’s too far gone in his creative obsessions to use his looks and voice in a deliberate way. For Turner, seduction is a foreign language—the only way he can express his passions is in barely controlled outbursts, not unlike the strokes of his paintbrush. In portraying the tiny cracks in William’s gruff, forbidding façade (from the striking shot in which he suddenly grabs his housekeeper’s breast to the grotesque crying fit in a brothel), Leigh is giving us an insight into a psyche that’s as self-preoccupied as it is yearning for human contact.

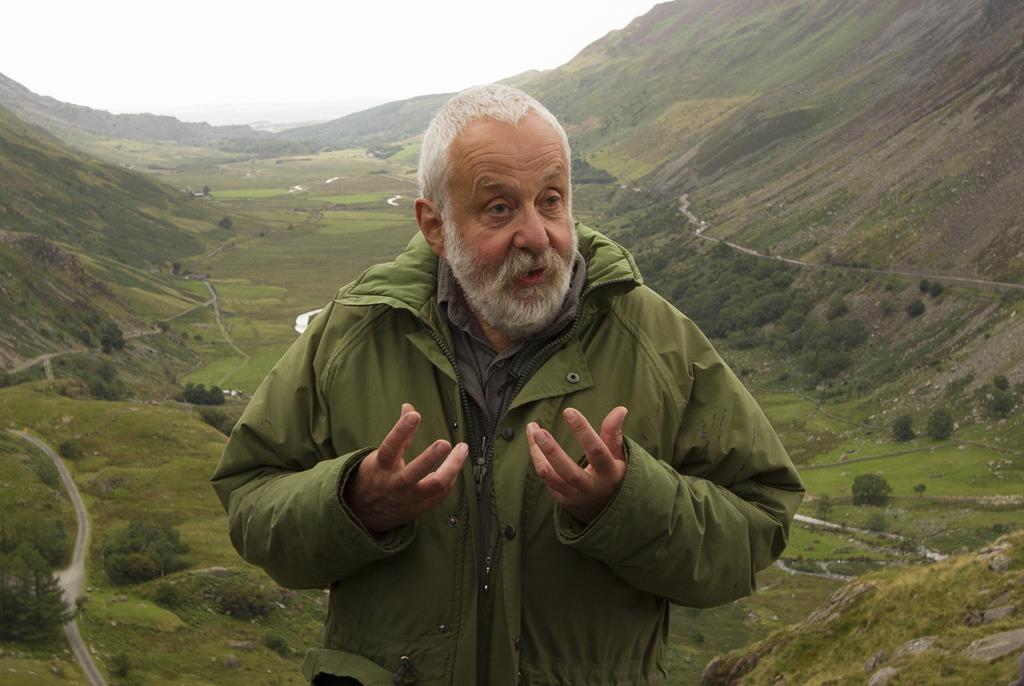

On the surface, nothing could be further from Mike Leigh’s temperament than a subject like Turner. Unlike the latter’s paintings, Leigh’s films have always been richly populated affairs, in which the idiosyncrasies of human behavior far surpassed any attention paid to things inanimate, like landscape or sunlight. That is not to say that Leigh’s films were never beautiful to look at, but their beauty was always private and inconspicuous: more Yasuijiro Ozu and Jan Vermeer than David Lean and John Constable. Here, it’s as if all that simmering passion for beauty has finally exploded and spilled out in a movie so gorgeous, I actually gasped at times at the beauty of its imagery.

It takes only a look back, however, to see how closely to his favorite themes Leigh is working in “Mr. Turner.” In fact, Timothy Spall had already played a silent, anguished picture-maker in the Palme d’Or-winning “Secrets & Lies” (1996), and even though the images he took were photographic in nature, his attention to his human subjects mirrors Turner’s fixation with light and its proprieties: a theme that by the end of the new film reaches a near-religious significance. It is first introduced by a great comical scene with Lesley Manville as a self-taught Scottish scientist, presenting Turner with the magnetizing potential of a prism (“I just put those wee bit particles into a chaos!”), and then grows into a crescendo in the film’s finale, with the grand declaration that “Sun is God”.

Spall’s character is also the latest incarnation of one of Leigh’s favorite personal archetypes: the silent, reclusive man whose creativity is severely tested and often results in suffering and self-destruction. That lineage is quite impressive by now—it starts somewhere with the character of Laurence in “Abigail’s Party” (1977) and includes such specimens as David Thewlis’s nihilistic rogue in “Naked” (1993) and Timothy Spall’s henpecked husband in “All or Nothing” (2002), the film whose somber tone “Mr. Turner” most closely resembles.

Although many people are bringing up “Topsy-Turvy” (1999) as “Mr. Turner”’s direct predecessor in Leigh’s filmography, the two are in fact quite different. Apart from the good cheer of Gilbert & Sullivan’s musical interludes being gone here, the new film is also about an artist profoundly incapable of compromise or even creative cooperation. It’s about an all-consuming endeavor that sends Turner to the top of a ship mast in one scene, so that he can look a raging sea storm in the eye. It is also suggested repeatedly that Turner’s fascination with elements is a consequence of his disillusionment with humans (slavery gets mentioned, as does Christian martyrdom and casual animal cruelty), whereas such misanthropy was absent from “Topsy-Turvy” altogether.

The movie is not perfect—there are a few negligible missteps, such as portraying Turner’s critics in the time-worn manner of ridiculing the blindness to one’s contemporary geniuses as moronic (was there ever a movie that would present a critic as simply puzzled by innovative work, instead of stupidly hostile towards it?). There’s also an unfortunate attempt at a crass anti-capitalist message, in which a rich businessman offers to buy all of Turner’s work and is not only refused (which would be perfectly understandable), but also chided for merely making the offer (which smacks of facile crowd-pleasing). These weaknesses don’t matter, though. I am happy to report that the 67th Cannes Film Festival kicked off with a movie so original, adventurous and beautiful; we will all be talking about it in the years to come.

Read the rest of our coverage of Cannes here and don’t miss the following special events at the festival:

Screening of “LIFE ITSELF,” in Cannes Classics: Monday, May 19, at 5 pm in Bunuel.

IN CONVERSATION with Steve James and Chaz Ebert about “Life Itself,” at the American Pavilion, Wednesday, May 21 at 11 am.

THE ROGER EBERT FILM CRITICS PANEL: at the American Pavilion, Thursday, May 22 at 3 pm. Moderated by Michael Phillips (Chicago Tribune), including Eric Kohn (Indiewire), AA Dowd (The Onion AV Club)