Listening to the radio and then standing in line for an hour, I heard plenty of regrets on Friday, the second day of the American Film Institute Festival. Hayao Miyazaki‘s “The Wind Rises” was screening at the historic Egyptian Theater in Hollywood as part of the festival. Miyazaki is retiring and with him, one wonders if Japanese animation is doomed to fall back into pre-Disney obscurity. For some people, Miyazaki is all they know of Japanese or even Asian anime.

While “The Wind Rises” opened in July of this year in Japan, then in South Korea (reviewed by fellow FFC Seongyong Cho) and Taiwan in September and it has screened at a few other film festivals (Venice, Toronto, San Sebastián, New York, Hawaii and Sitges), “The Wind Rises” was also playing for one week in Los Angeles and New York to qualify for the Oscar race. Oscar-nomination qualifying runs often have low key promotions to the general public. Some people in line at the Egyptian were unaware of the movie’s brief run at the Landmark in West Los Angeles. Many stood in line just to hear the undubbed version of the movie—they either understood Japanese or preferred to read subtitles. “The Wind Rises” will be released nationwide in February of next year in the United States and will likely be dubbed in English.

There are other reasons the AFI Festival attracted a long line for the movie. Some of the moviegoers had festival passes. The theaters are in easy walking distance along the historic Hollywood Walk of Fame and Hollywood is like a Cosplay party where you might see Darth Vader, Captain America, Charlie Chaplin or Marilyn Monroe impersonators vying for reflected fame.

The nightly red carpet gala presentations are well-attended by celebrities. The opening night gala had the added attraction of star Emma Thompson (“Saving Mr. Banks”) getting her feet and hands imprinted into cement at the historic and lavishly restored TCL Chinese Theatre (formerly Grauman’s and then Mann’s Chinese). The Chinese originally opened in 1927. The Egyptian opened in 1922. The Hollywood Walk of Fame was established much later in 1958.

At the AFI Fest, smaller films often have a Q&A following the screening. That wasn’t the case for this Miyazaki film which screened twice during the festival and attracted long lines with the only added feature being a display of original artwork.

Like the previous Studio Ghibli movie, the 2011 “From Up Poppy Hill” (directed by Miyazaki’s son, Goro), this movie contemplates war indirectly. The movie is not about the wartime deaths of many—soldiers and civilians. Instead, it’s a fictional account of Jiro Horikoshi, the main designer of the Japanese Zero, making this the only Hayao Miyazaki movie based on a historical character. Miyazaki was inspired by Hirikoshi’s commented that he only wanted to create something beautiful. Yet he did so much more.

During World War II, German airplanes were made of metal, yet Japan is a metal poor country. The Zero was a major accomplishment of because it was light, fast and made predominately of wood. Of Horikoshi’s Zero, The New York Times wrote in his obituary, the Zero “could climb faster and turn more tightly than its heavier United States counterparts, shot down so many American planes in the early stages of the war that ‘Never dogfight a Zero’ became a maxim for Allied pilots.”

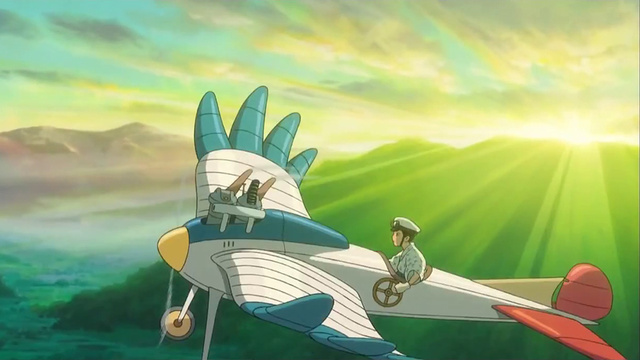

Miyazaki’s “The Wind Rises” begins with a boy who dreams about flying airplanes, but, the boy, Jiro, is limited by his myopia. He’ll never become a pilot. Miyazaki’s movies have dealt with flying before. In his second movie, the 1984 “Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind,” the young princess flies. The 1992 “Porco Rosso” was about an anthropomorphic pig who was a former Italian World War I flying act who became a bounty hunter to chase air pirates and the 1989 “Kiki’s Delivery Service” was about a girl witch who rides her broom and delivers packages. Miyazaki knows how to take on on flights of fantasy through wonderful cloudscapes and dreamscapes.

“The Wind Rises” takes its name from a Paul Valery poem: “The wind is rising, we must strive to live.” In his dreams, Jiro meets Italian aeronautical engineer Count Giovanni Caproni who encourages Jiro to build planes. Caproni would also be building planes during World War II, but the movie shows them only as men meeting in dreams, thinking more of the science and wonder of flight than their machines as instruments of war.

As a university student, Jiro survives the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923. The houses roll like waves. Traveling back to Tokyo by train, Jiro and other passengers must leave the derailed trains. Jiro helps an injured woman traveling with a girl named Naoko back to their home by carrying the woman on his back. Yet when he returns a few days later, fire has destroyed the girl’s home. He continues to search for her and eventually they meet and marry.

There’s a beauty in the ill-fated romance between Jiro and Naoko and the challenge of wood against the physics of flight. There might even be poetry in the mathematical equations that finally prove successful. The tragedy of grand achievements that go uncelebrated for citizens of the defeated nation aligns with Japan’s tradition of failed heroes.

In real life, Horikoshi became a lecturer at the University of Tokyo and was a professor, first at the National Defense Academy and later at Nihon University.

The movie isn’t interested in what Horikoshi did later in life; just his chase to construct the zippy Zero at Mitsubishi. In that respect, Miyazaki is backward-looking. “The Wind Rise,” like his other films is filled with a sense of nostalgia. Yet what about Japan in the present or the future? Other Japanese animators have looked forward. Tekkonkinkreet (鉄コン筋クリート Tekkonkinkurīto) Best Animated Feature for Japan in 2008 is about two orphaned street children dealing with yakuza. The surrealistic blend of computer and hand animation did well with critics, but didn’t get the kind of publicity that Disney affords Studio Ghibli releases. Asian animation on dark topics rarely do.

That doesn’t bode well for the AFI Fest offering, “The Fake,” a Korean animated movie about an evil man’s attempt to unmask greedy swindlers disguised as Christian evangelists. This isn’t a cheery dramedy like the 1992 Steve Martin vehicle, “Leap of Faith.” Our main character isn’t the priest at the center of all the hoopla.

In “The Fake,” the protagonist Min-Chul is a brutish, foul-mouthed wife-beating gambler. Min-Chul uses the money his daughter has earned and saved for college for his own gambling. When his daughter complains, he beats her. His daughter asks the young Father Sung to pray for her, but instead attracts the attention of his partner, a church elder and practiced con-man Choi, whose gaze drops to her girlish figure. Twisting words and faith, Choi will convince the girl to enter the sex trade as a karaoke hostess and her father will save her, but to what fate?

The animation is jerky, the colors are dark and muddy, the characters are repellant and everyone seems to be screaming in disgust or crying in anguish, but director Yeon Sang-ho isn’t condemning religion. According to his post-screening comments via interpreter, he was looking at how people listen to lies presented by a pretty nifty package while ignoring the truth that comes in a rough and ragged container. Subtle “The Fake” isn’t.

Yeon Sang-ho’s 2011 animated drama “The King of Pigs” was screened at Cannes Film Festival. The violent story about a bankrupt murderer screened at film festivals but according to IMDb, wasn’t released in the United States, playing only at the Austin Fantastic Fest. “The Fake” may find a similar reception after AFI Fest.

“The Fake” may find its way to a VoD venue. Consider that the Japan Academy Award nominated (which lost to the 2010 “The Secret World of Arriety”) “Colorful” never opened in the United States but is now available on HuluPlus. That’s despite dealing with a topical subject: bullying in schools.

The dark science fiction anime “The Sky Crawlers” lost to Miyazaki’s “Ponyo” at the 2009 Japan Academy Awards but never opened in the United States according to IMDb although I saw it at a smaller local film festival. The animated feature imagines an alternative reality where humanoids called Kildren never leave adolescence and are used to fight wars contracted by private companies in order to ease tensions amongst the human population: fake wars with an expendable population of subhumans. The director, Mamoru Oshii, also made the 1995 science fiction animation “Ghost in the Shell,” a movie that influenced the Wachowskis in their visualization of “The Matrix” series.

Some of those people in line for “The Wind Rises,” who claimed to love Japanese animation had never heard of Mamoru Hosoda or his 2010 “Summer Wars.” Hosoda’s 2012 “Wolf Children” (おおかみこどもの雨と雪 <i>Ōkami Kodomo no Ame to Yuki) won the Japanese Academy Award as did “Summer Wars” and his 2007 “The Girl Who Leapt Through Time.” “The Girl Who Leapt Through Time” beat Studio Ghibli’s Goro Miyazaki-directed “Tales from Earthsea.”

“Summer Wars” is about mathematics, online avatars and computer simulated virtual reality. What could be more topical in this age of social networking and Internet dependency?

“Wolf Children” looks at two children who are half wolf and half human and can control when they revert to their wolf nature. You’d think that with the popularity of vampires and werewolves brought on by the Twilight series, an animated feature that showed a family of werewolves deciding between life with humans versus life in the wild as a natural for American moviegoers.

“Wolf Children” opened in July of 2012 in Japan and premiered in the U.S. at a festival in March of this year. “Wolf Children” then played briefly in Southern California in April and again in September and will return again in December. In terms of family-friendliness, “Wolf Children” would be Disney-approval worthy.

On Netflix and Huluplus, there are plenty of animated features, most unfortunately dubbed. While as a Hayao Miyazaki fan, I am sad to hear of his retirement, Hayao Miyazaki is only one of many animators out of Japan. His sentimental tone and chirpy animals and characters have a far-reaching appeal, but he represents only one segment of Japanese animation. With Miyazaki’s retirement, will American audiences discover new directors or will Japanese animated features become something that only a few enjoy at festivals? At least now, we have online VoD option, but that too can be a means toward discovering the broader world of Japanese and Asian anime.

The AFI Fest continues until Thursday, November 14, 2013 in Hollywood.