Two and a half stars

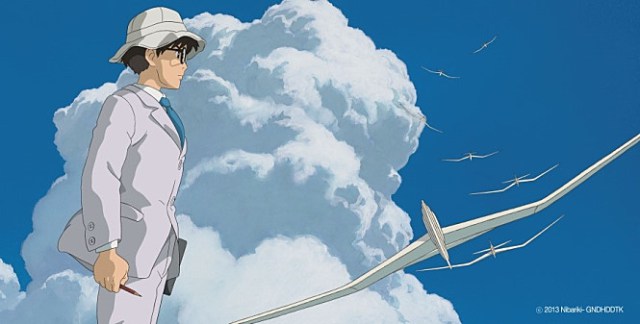

“The Wind Rises”, a new animation feature film which will probably be the last work from a great master of Japanese Animation, looks as lovely as expected, but I did an unthinkable thing I have never expected; I checked my wristwatch in the middle of the screening, and I was rather disappointed that it was only half over. Sure, I appreciated its beautiful animation and several gorgeous sights, but I felt the increasing dissatisfaction with its standard old-fashioned story mainly stuffed with nostalgic romanticism. It does fly as its wind rises, but everything merely floats by like the clouds in the sky, and even the darkness of World War II, which is inexorably connected with its hero’s life no matter how he thinks about its devastating consequences, feels like a trivial footnote attached to the story.

While also partially based on Tatsuo Hori’s 1938 novelette, the movie is inspired by the life of Jirô Horikoshi (voiced by Japanese animation director Hideaki Anno), who designed the Zero fighter plane for the Japanese Army right before World War II. I do not know how much the film is based on Horikoshi’s real life, but that does not matter much because the movie is peppered with nostalgia and fantasy from the beginning. Everything looks nice, lovely, and optimistic to the main characters except few things, and nothing seems to be going wrong even when they mention the Depression or the possibility of war.

And all Horikoshi cares about is making good airplanes. The opening scene shows young Horikoshi dreaming about flying his plane above his country hometown, and the movie gives us more fantasy moments through what Horikoshi dreams or imagines in his nerdy mind fueled by many aeronautics books. His childhood hero is famous Italian aeroplane designer Count Caproni (voiced by Mansai Nomura), and Horikoshi’s imagination soars along with this brash, hearty Italian man and his airplanes which instantly take us back to the memories of “Porco Rosso” (1992), one of the director/writer Hayao Miyazaki‘s famous works.

Horikoshi happily grows up with his plucky sister under the care of their generous mother(we do not see his father, by the way), and we soon see him as a grown young man hopeful about his future career as an aeroplane designer. He goes to the college in Tokyo, and his first day is quite unusual due to a sudden disaster which happens right before he arrives in Tokyo. The year is not mentioned, but you can easily guess it if you have ever heard about the Great Kanto Earthquake in 1923, which really caused lots of damages in Tokyo and the surrounding areas as shown in the film(While watching this part, some South Korean audiences may be reminded of the post-quake massacre of Korean immigrants by angry mobs).

The years quickly pass as the city is restored, and, after getting an aeronautical engineering degree, Horikoshi begins to work as an engineer in Mitsubishi Heavy Industries. His direct boss Kurokawa (voiced by Masahiko Nishimura) looks like a grouchy and fastidious middle-aged man at first, but he turns out to be fair, generous, and helpful. Horikoshi is gradually recognized as a young, bright talent to be supported, and he is sent to Germany with others to look around Germany’s advanced aeronautical technique. Later, he gets a chance to supervise the project for making a new fighter plane for the Japanese Army.

Meanwhile, our reserved but confident engineer falls in love with a young woman named Naoko Satomi (Miori Takimoto), whom he met during a rather dramatic Meet Cute moment during the Earthquake. They briefly got close after she was saved by him, and then they got separated, but, what do you know, he meets her again while he is having a vacation in a rural hotel which has a wide, beautiful green meadow nearby. The sky is refreshing, the wind is rising, the clouds are floating, the grasses are swinging, and she is painting right on the green hill when he reunites with her by coincidence.

This surely looks lovely with their clothes and the surrounding environments heavily influenced by European styles (even Thomas Mann’s “The Magic Mountain” is mentioned by one minor character), but Horikoshi and Satomi’s love story is your average doomed romance due to Satomi’s terminal illness, and their story gets a pretty predictable ending except that Satomi does not suffer from Ali MacGraw syndrome. After all, this is an animation feature film, so she always looks pretty regardless of whether her illness gets worse or not.

As indirectly or directly told by other characters, the storm is coming to everyone in the world, but Horikoshi does not seem to mind about that much because 1) he happily keeps working for his project under the protection of his company (Due to his close encounter with a certain character, he finds himself on the watch list of the secret police) and 2) he can spend the time with Satomi at home as a happily married couple even though their precious time is sadly too short for them.

Horikoshi must be well aware of what is going on in the world, but the movie does not delve deep into the interesting contradiction occasionally acknowledged by him and others around him. His dream and ambition are indeed idealistic and innocent, but his creation is ultimately used as one of the main weapons by the Japanese Army during World War II, and the movie just looks at the dire eventual consequences for around one minute. After everything has passed away, Horikoshi merely laments around the ending that every plane of his did not come back.

Did I get uncomfortable with the subject or contents of its story as a South Korean audience? I do not think so, because, despite a certain amount of boredom, I kept looking around and admiring the small touches and details in the painstaking efforts from Miyazaki and his animators on the screen. The movie is surely a lovely animation to be admired, and Joe Hisaishi’s score is effective as usual. While enjoying the flying sequences in dream and reality, I particularly liked the impactful scene depicting the landscapes shaken and rolled like carpets by the rapid shock waves of the earthquake, and I was also impressed by the aftermath scenes involving the fire, ashes, refuges, and ruins in the city(it is quite an irony that these gloomy sights leave more impression than the upcoming war in the film).

Hayao Miyazaki has always entertained me with his old and new works since I encountered his work for the first time through a pirate VHS copy of “Porco Rosso” (1992) in 1999. Three great animation films “My Neighbor Totoro” (1988), “Princess Mononoke” (1997), and “Spirited Away” (2001) further solidified my affection and admiration toward his works, and I enjoyed “Howl's Moving Castle” (2004) and “Ponyo” (2008) while gladly going back to “Nausicca of the Valley of the Wind” (1984) and “Castle in the Sky” (1986). All have their own enchanting moments, and they powerfully remind us that good animation films can be a lot more than mere entertainment for kids.

On the whole, “The Wind Rises” is not a bad animation film at all (well, how can we possibly imagine that from Miyazaki?), but it only leaves a mild taste with little impression and lots of disappointment – especially if you are an admirer of Miyazaki’s better animation films like me. It is not enchanting or charming enough to be recommended, and its story and characters are less engaging compared to the memorably colorful or complex characters we encountered in his other works.

Early in this month, Miyazaki publicly announced his retirement as the film was shown at the Venice International Film Festival. Although he has been keeping implying about his retirement for many years, he seems to be really serious in this time considering his age, and I respect his intention to exit quietly with this mild nostalgic work as his swan song, but I cannot help but think that he could have gone more boldly with his imagination or his humanistic belief which is certainly far from the current right-wing Japanese government as reflected in his recent public statement.

Compared to his towering career achievement, “The Wind Rises” feels like a minor footnote at the end of his illustrious career, and that will be a shame if his announcement of retirement really turns out to be true. Seriously, as feeling more conscious of its overlooked dark side, now I wonder whether my viewing of this film could have been improved by a double feature show with other Japanese animation “Grave of the Fireflies” (1988). That film really looks at the reality of World War II, but “The Wind Rises” keeps talking about how wonderful it was before the war. Yeah, it looks lovely, but, alas, that is all for us.

Sidenote: I learned later from the review by Mark Schilling that the title of the film is inspired by a line from the Paul Valery poem “Le Cimetiere Marin (The Graveyard by the Sea)” that translates as: “The wind is rising! We must try to live!”