Oh, the places you’ll go for a film festival. Big cities, small towns, resort destinations, international ports-of-call, middle of nowhere and the middle of everything. For years, I’ve saved up money to travel to festivals around the county. I justified any expenses by tying it to work, so I could trick myself into thinking I was visiting parts of the country I’ve never seen before. In reality, I was mostly cooped up somewhere near the back of the theater.

I’ve traveled more this year than in my previous seven years as a critic combined, like an “Eat Pray Love” trip, but more about movies and catching up with friends in different cities. I headed west, south and back to the northeast, only to do it all over again.

I finally took my last festival-related trip of the year last month to Key West for their film festival, an easygoing event so relaxed, it almost unnerved this native Floridian. Still, in-between catching up with a few highly anticipated movies like “Shoplifters” and “Cold War,” I wanted to make time to explore the island and break my habit of working longer than I spent time at the movies or outside. I had a feeling that on this trip, I should take a moment to look around, not just at the screen.

As soon as I walked off the tiny prop plane and onto the island’s airstrip, there was a statue welcoming visitors to the Conch Republic, the affectionate nickname for Key West. On the roof of the small airport was a concrete buoy marking the 90 miles to Cuba—where my family is from—with friendly brown figures standing in for Cubans on one side and smiling white figures signifying Americans on the other. It was the friendliest depiction I’ve ever seen of U.S.-Cuban relations in all my life. I immediately took a photo and sent it to my mom for a laugh, as I do whenever I find something interesting to show her.

My mom usually doesn’t offer much advice when I travel except “don’t,” but this time she gave me an assignment: I had to visit the southernmost point of the United States. Some relatives have gone there, and now, so should I. It’s the closest you can get to Cuba without leaving the safety of the States. Alright, I promised her. I’ll go later in the week.

The Key West Film Festival headquarters itself in the San Carlos Institute on one of the most tourist-lined streets this side of South Beach. It’s not uncommon for a festival to screen its biggest movies in some historic theater, but I didn’t realize the significance of the place until I got there. I was in awe of at how much Cubaness I stumbled upon. A Cuban flag greeted me as I picked up my badge on the first night, and as I looked around, I recognized the face of José Martí, one of the fathers of Cuban independence and its most famous poet. I found his image at least half a dozen more times on my way to the theater inside, including a statue and least one painting of a white rose in reference to his best-beloved poems. Inside, large photographs from each of Cuba’s provinces hung on the walls, including the names of the parts of Cuba my family comes from. I spotted yet another Cuban flag near the old proscenium arch.

The place was a Cuban cultural center, one of the oldest in the country. Established in 1871 by Cuban exiles fleeing Spanish rule, the San Carlos Institute even hosted Martí as he was rallying support for Cuban independence. At one time in its history, it was a racially integrated bilingual school in a state that fought such progressive measures. It had almost fallen into ruin were it not for the preservation efforts of generations of Cuban Americans and newer arrivals of Cuban exiles.

On my last full day on the island, I knew I had to walk to the southernmost point on the island. I could not pass by Martí’s statue again without doing what my mom asked. It felt too deep a betrayal. So I walked, passing by Key West’s grand old Floridian homes with large windows, groups of wedding parties on bike tours and the occasional pack of stray chickens. When I finally got to the tourist hub, there was a block-long line just to get a photo with the black, yellow and red concrete buoy. Instead of waiting in the Disney World-length line, I took photos for my mom of the place. I could not see Cuba, but that stopped no one in the crowd of dozens from staring into the distance.

Some people chattered excitedly, others were in near reverential silence, just about everyone near the barrier fence with me spoke Spanish. I could hear the thick Cuban accents of a few old-timers, and in their somber tones, it sounded as if this might be as close as they’ve ever gotten to the island since they fled. For most people, this little concrete corner of the world is a roadside tourist trap. For those in the Cuban exile community who will never go back, it’s like a gravesite, the closest they can physically get to a lost loved one. For me, it was a reminder of how tenuous a bridge those 90 or so watery miles are and how easily it can collapse at a politician’s whim.

I felt homesick and alone at that moment. No one else at the festival seemed to notice this venue’s history, and I wondered how many other times have I floated in and out of regional festivals having done the same. Later that evening, I passed by Martí’s statue guilt-free and climbed up a set of ornate stairs to the building’s second floor for jury deliberations. Sequestered in a library filled with Cuban history, I was almost too distracted by the volumes of ancient looking books and the no less than three paintings and a bust of the revered poet. It was enough to remind me of my first trip to Havana, where I’m certain no city block exists without Martí’s blessing. After the judging was done, one of my colleagues offered to take my picture in front of one of the many paintings in the room. I took him up on the offer for my mom.

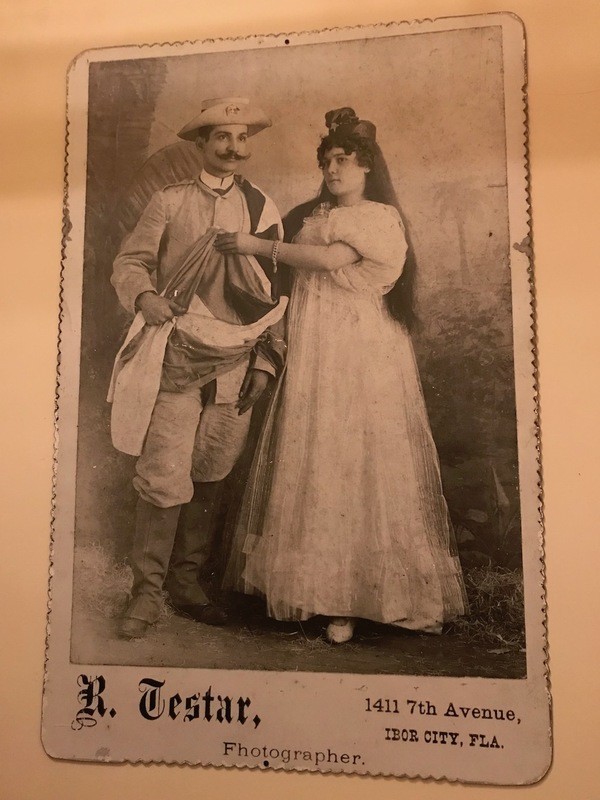

I left the library and looked around once more before going back downstairs for the rest of the festival. On a wall hung a large photograph of Cuban couple from what looked to be the late 1800s: a proud man in his starched white mambí uniform and a Cuban flag draped over his shoulder and a young woman with waist-length dark hair wearing her best lace dress. They were advertising a photographer’s studio in Ibor City, the historic Cuban district in my hometown of Tampa now known as Ybor City. Even in this faraway island, I was never far from home.

When I tell my family about the festivals I visit, they imagine I have time to go skiing at Sundance, wait in the hours-long line for barbecue in Austin during South by Southwest or take a train across town to see some historical landmark. For many of us covering a festival, what’s on the screening schedule are the only things we can get to on a given day. Venturing outside the festival map can be a challenge, but should I be lucky to keep traveling next year, I should have to do that more often. I can’t always expect history to find me first.