Hirokazu Kore-eda’s Palme d’Or-winning “Shoplifters” opens with a perfectly calibrated scene that sets the table for what’s to come. A man and a boy are in a store. They keep making eye contact, moving slowly through the aisles. They clearly have a level of non-verbal communication that feels like a ritual. They’ve done this before. They will do this again. And doing this brings them somewhat closer to each other, even if it’s illegal. Of course, what they’re doing is shoplifting, but we instantly get the feeling that they’re doing it to survive. They’re getting food for their family, not taking trinkets from a fancy store.

On the way home that night, just after commenting on how it’s too cold to go back and get some forgotten shampoo, the man and boy see a girl on a balcony. We get the impression they’ve seen her before. Despite their obvious need, the man offers the girl a croquette, and she ends up coming home with them. We learn that the man is named Osamu (Lily Franky) and the boy is named Shota (Jyo Kairi). At home, there are other mouths to feed. We meet the mother named Nobuyo (Ando Sakura), another woman named Aki (Matsuoka Mayu) and a grandmother (Kiki Kilin). And now there’s a new mouth with a girl named Juri. When Osamu and Nobuyo go to take the girl back that night, they hear a violent scuffle between parents who likely haven’t even noticed their daughter is gone. Nobuyo just holds Juri a little tighter and we know they’re not giving her back.

Nobuyo and Osamu justify their action by saying it’s not a kidnapping if you don’t ask for a ransom. It’s similar logic to how Osamu justifies stealing to Shota—telling him it’s OK if it’s not someone else’s property and items in a store don’t belong to anyone yet. It’s OK as long as the store doesn’t go bankrupt. “Shoplifters” is full of these gray areas. What exactly does family mean? Does giving birth to someone automatically make you a mother? Kore-eda has confronted the definition of family before in films like “Like Father, Like Son” and “Nobody Knows,” but this is one of his most nuanced, layered examinations of the concept. Nobuyo and Osamu shelter, feed, dress, and care for Juri more than her biological parents and yet they are not her “family.”

For the bulk of “Shoplifters,” Kore-eda works in a beautiful register that feels both detailed and genuine at the same time. We get to know these characters so deeply, watching them all at their jobs. Osamu is a day laborer until he gets into an accident. Nobuyo works a laundry shift, from which she takes trinkets left in clothes. Aki is a “companion,” someone who does sex shows but longs for a deeper connection with one of her clients. There are hints of greater secrets and a more complex past than you might first think in the Shibatas, but there are also numerous scenes of average domesticity.

And then Kore-eda drops the floor out from under the Shibatas, revealing there are a lot of things we don’t know about this makeshift family. The final half-hour of “Shoplifters” is some of the most emotional, powerful filmmaking of the year, and it’s thanks to how delicately Kore-eda has drawn these characters over the 90 preceding minutes. They feel as three-dimensional as any this year, thanks to Kore-eda’s humanist storytelling but also his expert direction of a truly amazing cast. Lily Franky is fantastic, but Ando Sakura is the stand-out—the way she conveys her character’s deep well of conflicted emotions in the final scenes is breathtaking. It’s one of the best performances of the year, a stand-out in an incredibly pure ensemble.

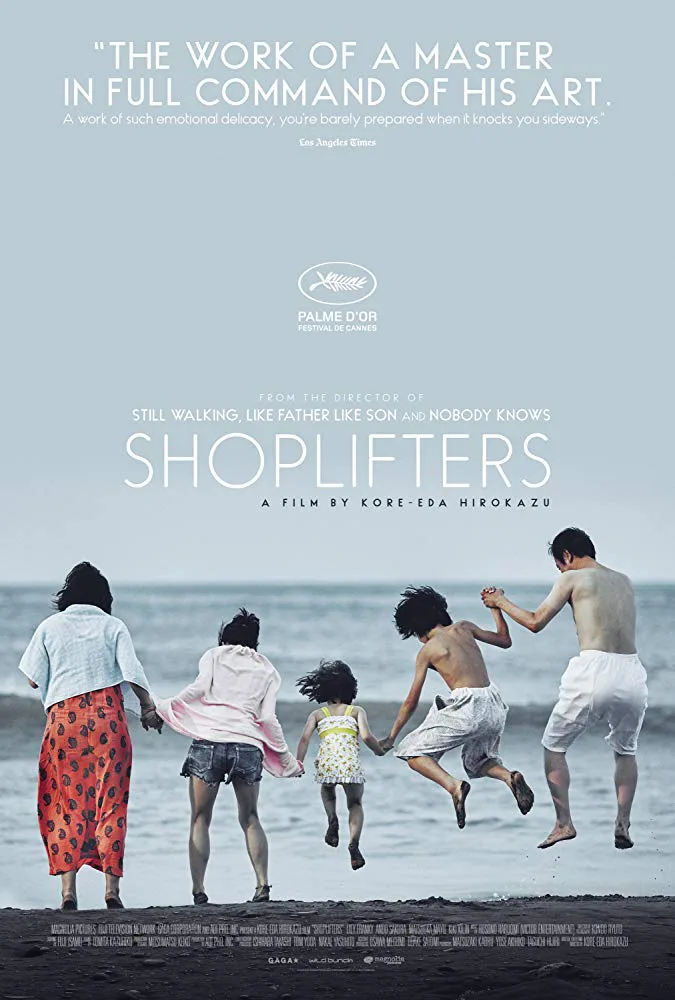

In many ways, “Shoplifters” feels like a natural extension of themes that Kore-eda has been exploring his entire career regarding family, inequity, and the unseen residents of a crowded city like Tokyo. With this movie especially, his characters and their predicament are not merely mouthpieces for the issues that interest him but fully-realized people who feel like they existed before the film started and will go on after it ends. The final shots of “Shoplifters” haunt me—two kids, one looking back and one looking out, both changed forever.