Billy (Silver Dollar) Baxter traveled to the Cannes Film Festival every year with two old friends, Herb and Anna Steinman of New York City. He always introduced Mrs. Steinman as “Jack Nicholson’s shrink,” and Herb as “the retired millionaire and my old buddy-boy.” From time to time over the years, Baxter and Steinman had purchased the rights to films at Cannes, and released them in the United States. Their purchases included “The Umbrellas of Cherbourg” and Lina Wertmuller’s “Love and Anarchy,” and in 1977 they were hot on the trail of a Canadian film titled “Outrageous!“

The rights to the Canadian film, which was about a friendship between a troubled girl (Hollis McLaren) and an equally troubled female impersonator (Craig Russell), were being negotiated by Dusty Cohl, a bearded Toronto lawyer.

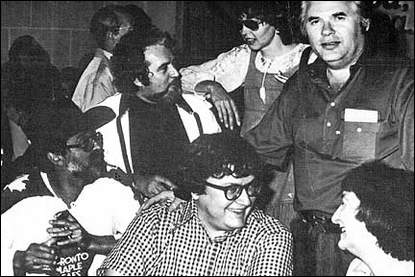

The story of how Cohl and his wife, Joan, discovered the festival was already a Cannes legend. In 1969, it was said, they were vacationing on the Riviera, found a parking place in front of the Carlton Hotel, walked in to ask for a room, and found themselves in the middle of the festival. Cohl immediately took to the carnival atmosphere, and hung around the Carlton for a week, having deep discussions about film with everyone he met. Cohl always dressed in the same uniform in the daytime: faded blue jeans, a T-shirt, a large black Stetson cowboy hat with a star pinned to it, and a long Cuban cigar. All he had to do, in this uniform, was describe himself accurately, as a Toronto lawyer, and everyone assumed he was a film producer. By the time Joan and Joan returned home that year, they knew they had found a mission in life: to create a film festival in Toronto, since every city, obviously, should have one. And they did. The only fact in their story that sounds unlikely is the free parking space in front of the Carlton.

Dusty and Joan were to daytimes on the Carlton Terrace what Silver Dollar Baxter was to nighttimes in the Majestic’s American Bar. Indeed, like the royalty of neighboring principalities, they one year exchanged signing privileges at the two bars—and then each immediately raced to the other’s bar to sign all the tabs he could. For 15 years at the Cannes Film Festival, Dusty and Joan Cohl were probably responsible for introducing more Canadians to more people from elsewhere than any two other people in Canadian history.

As I’ve said, Dusty was at Cannes representing the American rights to “Outrageous!,” and Billy and Herb decided to bid for them. They were thus assuming the classic Cannes roles of Seller and Buyer, and I asked if I could observe their negotiations as an educational experience. They agreed, with the provision that in any reports of their talks, I would use “symbolic amounts” rather than actual dollars. I said I would.

On the day the negotiations were set to open, Billy and Herb asked me to meet them at 11 a.m. in the Majestic bar. It was nearly empty at that hour—the festival in those years was still centered around the old Palais, down at the other end of the Croisette, and the Majestic remained secluded. Baxter and Steinman made a strange team. Steinman was a tall, robust, balding businessman in his late seventies, with a kind face and gentle voice. Baxter, who could have been created by Damon Runyon, was a red-faced Irishman with a round little belly, who when he met a pretty girl would tell her, “I’ve been tubbed, I’ve been scrubbed, I’ve been rubbed. I’m huggable, lovable and eatable. I learned that off a baked potato.”

Steinman said he wanted an iced tea. “Irving!” shouted Baxter. “Brang ‘em on!” Everywhere in the world, Billy called all waiters “Irving!” Loudly. He got away with this because he tipped with silver dollars. He had discovered that French waiters would rather have an American silver dollar than a $5 bill.

Billy started briefing Steinman. (All figures here have been replaced with Symbolic Amounts).

“Herb, you know, and I know, that this is a hot film. But does Dusty know that? This is his first time up against experienced operators like ourselves. Okay. What do we use for openers? For “Love and Anarchy,” we paid $100,000 for the U.S. rights, and we cleaned up. So we gotta tell Dusty we will only pay him half of what we paid for “Love and Anarchy,” right?”

“Sounds okay to me, Billy,” said Steinman.

“Only get this. What we tell him is, we only paid half of what we actually did pay for “Love and Anarchy” — so that in offering him half, we’re really offering him a quarter, right?”

“In other words,“ said Steinman, “25 percent.”

“You got it,” said Billy. “We tell him half, but what we tell him is half of half. Got that?”

“I think so, Billy.”

“Okay. We’re all set. Here he comes now.”

Dusty Cohl walked into the bar and sat down, carefully placing his black cowboy hat on the next table. He was dressed for business, with a gray summer suit on over his Dudley Do-Right T-shirt. He passed around cigars.

“Irving! Brang ’em on!” Baxter shouted. “Johnnie Walker! Black Label! Generous portion! Clean glass! Lotsa ice! Olives! Nuts! And clean up this shit off the table! And brang Mr. Cohl here whatever he wants! And doop-a-dop-a-doo for everybody else!”

Dusty opened by pleading innocence: “I’m a guy who is new to this, guys. I’m feeling my way, I’m learning as I go along, I appreciate the opportunity to talk with you gentlemen, and maybe we can make a deal that will make everyone happy.”

“Cut the crap,” Baxter said. “You got a film here about a Canadian pricksickle aficionado, and nobody wants it. You’re talking to the guys who put Lina Boop-a-doop on the map. How much you want for this movie?”

“I was thinking twelve-five up front, against some guarantees and percentages,” Cohl said.

Baxter was momentarily stunned. Cohl had opened by asking for only half of what Baxter was prepared to offer in his opening bid. Before he could open his mouth, mild-mannered Herb Steinman spoke: “We can only give you half of ‘Love and Anarchy’.”

Baxter’s face turned more pink.

“Irving!” he screamed. “On the double!” This was a diversionary tactic. He turned to his partner. “Herb,” he said urgently. “Think! We can only give half of ‘Love and Anarchy.’ Do you see what I mean?

“That’s right, Billy, half of ‘Love and Anarchy’.”

“Not half, Herb — half!!”

“Like I say, half.”

Dusty Cohl sat patiently.

“HALF! Of ‘Love and Anarchy’!” Baxter shouted, desperately trying to get Steinman to read his mind. I tried to do the mental arithmetic. Billy was trying to get Steinman to make a three-stage transition: To think, not half of the original price, which would have been $50,000, or half of that price, which would have been their original opening bid of $25,000, but half of that, which would have been $12,500 — one-eighth of the actual price of ‘Love and Anarchy.’ Then, presumably, Cohl would make a counter-offer, and they would negotiate from there. But could Steinman make the mental leap?

“Right, Billy,” said Steinman. “I know what you’re thinking. Half of ‘Love and Anarchy’.”

“But are you talking half, or are you talking half?”

“I’m talking half of half.”

“No! Not half of half. Half of half of half.”

“This is not sounding good,” said Cohl.

Baxter leaned forward, trying to project his thoughts into Steinman’s mind.

“The original half?” asked Steinman.

“The revised original half,” said Baxter.

“Half of that?”

“Herb. Think. “Half of ‘Love and Anarchy.’ Concentrate! Do you know what I’m thinking when I say, half of ‘Love and Anarchy?’”

“Billy,” said Steinman. “I know what you’re thinking when you say half of ‘Love and Anarchy.’ That’s not the problem.”

“Then what’s the problem?”

“Billy, suddenly, I don’t know what you’re thinking when you say all of ‘Love and Anarchy’.”

* * *

Reprinted from “Two Weeks in the Midday Sun,” Ebert’s book about the Cannes Film Festival.