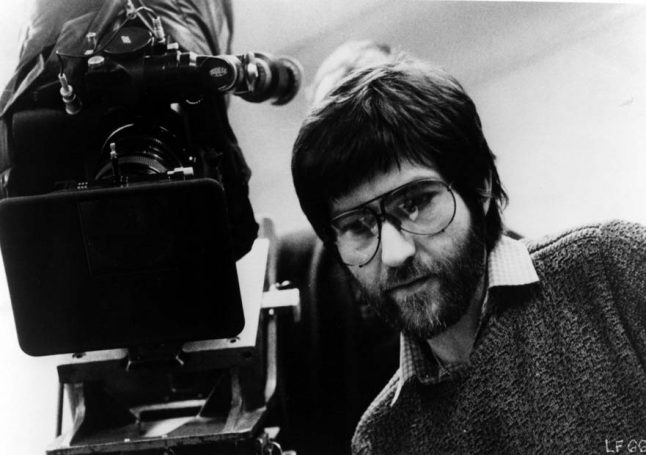

The conventional wisdom regarding Tobe Hooper, who passed away yesterday at the age of 74, is that he was a filmmaker who created an undeniable classic right out of the gate but failed to live up to the promise of that early achievement. As anyone who ever saw one of his films could tell you, however, his name and the word “conventional” never sat together easily in the same sentence. Yes, it is true that his 1974 opus “The Texas Chain Saw Massacre” transcended its low-budget origins and grisly (if undeniably effective) title to become one of the most famous and influential horror movies of all time. But his subsequent career, although dotted with more than its fair share of controversies and ill-chosen products, contained a number of impressive genre efforts that any filmmaker would be proud to have on their resume.

Tobe Hooper was born in Austin, Texas on January 25, 1943 and by the age of 9, he was already making movies at home with his father’s 8mm camera. In the 1960s, he began making commercials and industrial shorts. From there, he made the 1964 short “The Heisters,” a 1968 documentary for PBS about folk trio Peter, Paul and Mary and his feature debut, “Eggshells (An American Freak Odyssey),” a fantasy-drama about the devolution of the peace movement that won acclaim at some film festivals but never received a formal release. After that, he went back to the University of Texas at Austin to work as an assistant film director and documentary cameraman when inspiration, as the story goes, struck him while stuck in the hardware section of a crowded department store. While trying to think of a way of getting through the mob of people, his eyes supposedly happened upon a chain saw that was sitting there. Using the story of the infamous Ed Gein (whose notorious misdeeds had already helped to inspire “Psycho”) as a leaping-off point, he and co-writer Kim Henkel wrote a script and with a minuscule budget, a short schedule, a cast of unknowns and an undeniable grabber of a title, he went off to make “The Texas Chain Saw Massacre.”

Since the film was released in 1974, countless legends have sprung up regarding its arduous production (many of those stories were compiled in Gunnar Hansen’s enjoyable 2013 memoir “Chainsaw Confidential”), its tumultuous initial reception (including a near-riot that supposedly developed when it was sprung without warning on a preview audience that was expecting to see the decidedly different Walter Matthau heist thriller “The Taking of Pelham 1, 2, 3”) and how it inspired outrage and outright banning throughout the world because of its supposedly repulsive content. None of those stories would have taken hold at all if the movie itself didn’t actually deliver the goods. Not only was it obvious right from the start that “The Texas Chain Saw Massacre” was one of the great horror films of its time, it was one of the few films of its type that has not lost a single iota of its ability to freak viewers out. Most horror films, even the best, tend to find that their impact gets dulled by the passage of time—Hooper’s film can still knock even the most jaded viewers for a loop.

There are a couple of key reasons why it has maintained its power. There is the fact that it simply doesn’t look like a conventional genre effort. With its artfully grimy look, courtesy of cinematographer Daniel Pearl, a cast of eventual victims who looked and acted more like real people rather than the usual caricatures and a production difficult enough that the line between the pain endured by the characters and the pain endured by the actors playing them all but dissolved, it felt less like a regular horror film and more like some kind of horrific documentary. For another, most horror films, even the best, have a tendency to fit into certain rhythms and once you figure them out, you can oftentimes begin to anticipate the ebb and flow of the moments of terror. With “Chain Saw,” Hooper directed it in such a way that blurred those rhythms—his scares never occur at the expected time and in the expected way. Viewers are constantly kept off-balance throughout, and no matter how many times one sees it, it is still hard to place exactly where the big scares occur until they are finally sprung. Finally, and perhaps most perversely, a lot of the impact comes from the fact that, despite its reputation as one of the goriest films ever and that title, there is actually relatively little on-screen violence to be had—only one person is actually killed by a chain saw and the details are kept to a minimum. Hooper did this in an attempt to secure a more commercially viable PG rating for the film but it backfired because he did his job too well—his suggestions of violence through artful editing and sound effects proved to be far more shocking and impactful than gallons of fake blood could have ever hoped to accomplish.

“The Texas Chain Saw Massacre” was a big hit, though the vagaries of independent film distribution in those days meant that the people who made the movie would see very little of that money, and in a perfect world, Hooper should have been able to go on to a long and successful career but his career faced some notable speedbumps immediately. His follow-up was “Eaten Alive” (1976), another Ed Gein-inspired effort about a crazed Texas hotel owner (Neville Brand) who would kill those who upset him and feed their bodies to the giant crocodile that he keeps as a pet in the swamp out back—although enlivened somewhat by an oddball cast including “Chain Saw” survivor Marilyn Burns, Mel Ferrer, Carolyn Jones, Kyle Richards, William Finely and future horror icon Robert Englund, the film, which was taken away from Hooper and recut by the producers, is serviceable at best and certainly has none of the impact of his previous effort.

From there, he signed on to do another horror film, “The Dark,” but was fired during the production and replaced by John “Bud” Cardos. (He would later leave the production of the Klaus Kinski thriller “Venom” after a few days shooting.) He was able to rebound from that with a two-part TV movie adaptation of Stephen King’s modern-day vampire novel “Salem’s Lot” (1979) that managed to provide a few genuinely unnerving moments despite the limitations of network broadcast standards of the time and was deemed good enough to be reworked into a theatrical release in Europe. That was followed by “The Funhouse,” a weird effort following a quartet of teenagers who decide to spend the night in a carnival funhouse and are pursued by a deformed monster hiding his hideous visage behind a Frankenstein mask. Although generally written off or completely overlooked by all but the most ardent horror fans, this film, for all of its evident flaws, is of some interest because of the genuinely creepy atmosphere than Hooper creates and because of some authentically perverse moments tossed into the mix.

Despite his spotty record with producers, one of the most powerful in Hollywood at that moment, Steven Spielberg, hired him to direct “Poltergeist,” a horror story in which an ordinary nuclear family is terrorized by malevolent spirits haunting their home in the middle of an ideal-seeming housing development that has a secret or two of its own. This big-budget foray into studio-made horror was a large hit when it premiered in the summer of 1982 but instead of being able to bask in the glow of a sizable hit, Hooper was dogged almost from the start with rumors that he had virtually nothing to do with the film and that it was Spielberg who actually directed it. Debates as to who did what on that film have raged for decades and every few years, someone will publish a new article claiming to reveal exactly what happened during its production. If the end result was more of a collaboration than anything else, it was one in which Hooper was as valuable a contributor. Alas, Hollywood didn’t quite see it that way, and the film’s success was attributed almost entirely to Spielberg with Hooper getting virtually nothing out of it in the end.

After directing a controversial video for Billy Idol’s song “Dancing with Myself,” Hooper signed up with Israeli producers Menahem Golan and Yoram Globus, who had just taken over Cannon Films with designs on conquering the American film industry, to make a couple of big-budget productions. The first project, “Lifeforce,” was a jaw-dropping sci-fi/horror extravaganza in which a trio of space vampires (who suck energy rather than blood) found in the tail of Haley’s Comet are inadvertently brought to London and get loose, infecting the population and threatening the entire world. One of the most genuinely batshit crazy films that you will ever see, this heady cocktail of wild special effects, cheerfully hammy performances and straight-up weirdness is one of those rare films that starts up already cranked up to 11 and somehow manages to sustain the lunacy throughout. (I wrote extensively about “Lifeforce” here in 2013.) Alas, few sparked to its madness and it went down as a major flop, a fate that also befell Hooper’s next film, an expensive remake of the sci-fi classic “Invaders from Mars” (1986), a film that had some nifty stylistic touches here and there but never quite came close to approximating the dreamlike power of the 1953 original.

With two big flops on his resume, Hooper finally resigned himself to make the one film that people seemed to want from him, a sequel to his first big triumph. However, rather than the standard retread that many were expecting, his “The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2” (1986) proved to be anything but. The basic premise—a radio host (Caroline Williams) finds herself being victimized by the infamous Sawyer family while a relative (Dennis Hopper) tries to track her down—may have sounded conventional enough but the execution was decidedly different. Having been unfairly charged with making a gore-fest the first time around, Hooper decided to go the opposite way and make things so gruesome that the material transcended horror to become more of a Grand Guignol-style comedy than anything else. It proved to be so grisly that the film went out unrated, a move that helped to doom its commercial chances.

Beyond the blood, Hooper and co-writer L.M. Kit Carson (whose previous project was co-writing the slightly different “Paris Texas”) took a more frankly satirical approach that poked fun at everything from the materialism of the Reagan years (the Sawyer family had transformed their cannibalistic tendencies into a profitable concern by becoming purveyors of gourmet chili, even if they occasionally have to assure that the thing that someone found in their bowl is not a tooth but merely a peppercorn) to the gun culture of the day with chainsaws replacing conventional armaments. (The sight of Dennis Hopper wearing his chainsaw holster is truly something to behold.) They even manage to develop the character of Leatherface himself by having him sort of fall in love with the hapless heroine, leading to any number of sight gags involving the phallic nature of his weapon of choice. One of the truly unsung films of the era, I would actually go so far as to preferring it to the original and consider it to be Hooper’s ultimate masterpiece.

Unfortunately, it would prove to be the last great work of Hooper’s career. Although he would continue to work steadily throughout the years, he would never again have the resources of influence that he maintained in his heyday. Much of his work was done for television, including episodes of “Amazing Stories,” “The Equalizer” and the pilot to the “Freddy’s Nightmares” anthology and TV movies like “I’m Dangerous Tonight” (1990) and “Body Bags” (1992), an anthology film also featuring contributions from John Carpenter. His feature films, none of which received any real distribution, included “Spontaneous Combustion” (1990), the Stephen King adaptation “The Mangler” (1995), a remake of “The Toolbox Murders” (2004), “Mortuary” (2005) and “Djinn” (2013), which would be his final directorial effort. In 2011, he published the horror novel “Midnight Movie.”

Rather than the one-hit wonder that some writers of film history may dismiss him as, Tobe Hooper was one of the most unique talents to emerge from the horror genre in the last half-century or so and while his track record as a whole may be uneven, his high points—his two “Chain Saw” movies, “Salem’s Lot,” “Poltergeist” and “Lifeforce”—put the efforts of many other filmmakers of his era, regardless of genre, to shame. He was utterly incapable of giving viewers a safe and predictable night at the movies and it was that refusal to do so that will allow his movies to continue to shine for decades to come. One of his last projects saw him contributing to the cable anthology series “Masters of Horror” and if ever there was a filmmaker deserving of that designation, it was him.