When I was a wee lad in the initial throes of the cinemania that would eventually consume my life, my venerable mother sat me down in front of the television one afternoon and informed me that the Three O’Clock Movie that day was something that I absolutely had to see. This was a big deal because, even to this day, my mother has never been much of a movie person, and the notion that one would make enough of an impression to warrant a recommendation is still somewhat astonishing. For the next 90 minutes, I watched the tale of an ordinary businessman pursued through the desert by a monstrous 18-wheeler piloted by an unseen driver with a serious case of road rage, and I was transfixed by every single one of them. Put it this way — if I hadn’t already begun a love affair with the movies, I would have right there and then.

That film, of course, was “Duel,” the landmark 1971 TV movie that would be the first major exposure that most people would have to the work of its young director, Steven Spielberg. I know it was for me, and to this day it remains my second-favorite Spielberg film. However, that day would also introduce me to a figure who would prove to be just as significant — if not more so — in popular culture, and that was Richard Matheson, who wrote both the screenplay for the film and the original short story that it was based on. Here was a man who may not have had the instant name recognition of the likes of Spielberg or Stephen King or Ray Bradbury, but whose work in a career that would encompass seven decades influenced anyone who encountered it, regardless of the medium he was working in.

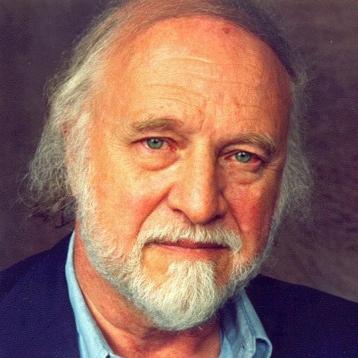

Matheson, who died today at 87, wrote twenty-eight novels, including the back-to-back classics “I Am Legend” (1954) and “The Shrinking Man” (1956), plus a huge number of short stories that would lead him to be regarded as one of the great science-fiction/fantasy/horror writers of his time by critics and readers alike. Many of these books and stories would go on to be adapted into such films as “The Incredible Shrinking Man” (1957), “The Legend of Hell House” (1973), the big-screen version of “Twilight Zone: The Movie” (1983), “What Dreams May Come” (1998), “The Box” (2009), “Real Steel” (2011), and no fewer than three official takes on “I Am Legend” — “Last Man on Earth” (1964), “The Omega Man” (1971), and “I Am Legend” (2007).

Matheson also wrote a number of original screenplays and adaptations of other people’s work, most notably the Edgar Allan Poe films “House of Usher” (1960), “The Pit & the Pendulum” (1961) and “The Raven” (1963) that he did for Roger Corman. He even found success in television by penning episodes for such landmark shows as “The Twilight Zone” (including adaptations of his short stories “Third from the Sun,” “Little Girl Lost” and the immortal “Nightmare at 20,000 Feet”) “Thriller,” “The Alfred Hitchcock Hour,” “Star Trek” and “Rod Serling’s Night Gallery” and the hugely popular TV movies “The Night Stalker” (1972) and “Trilogy of Terror” (1975).

Matheson’s genius came from his ability to take the fantastical and couch it in terms that contemporary audiences could instantly relate to on a more personal level than most genre fiction of the time. He was enormously influential. As Roger Ebert wrote in Roger Ebert’s Movie Home Companion, his approach “anticipated pseudorealistic fantasy novels like Rosemary’s Baby and The Exorcist.” Although Stephen King would often be cited as the writer who moved horror from Gothic mansions to the suburbs, he was merely following in Matheson’s footsteps (which King has acknowledged on many occasions).

Take, for example, “Nightmare at 20,000 Feet,” which has been told three ways — in Matheson’s original short story, on TV’s The Twilight Zone, and in the same-titled 1983 movie anthology — with standout results each time. It tells of an extremely jittery man — recently released from an institution following a nervous breakdown in the earlier versions and terrified of flying in the movie — whose already-rough airplane trip becomes even more nightmarish when he sees, or thinks he sees, a monster on the wing of the plane futzing with the engine. On its most basic level, “Nightmare at 20,000 Feet” deals with one of the more durable concepts in all of fiction — the idea that you know that something awful is about to happen but cannot convince anyone that what you are saying is true.

On top of that, Matheson adds the concept of airline travel, which was only then beginning to become a regular thing for the masses, and exploits one of its more unsettling, if largely unspoken, elements — the fact that once the doors close and the plane takes off, the passengers are essentially hostages who have little if any control over their fates. By expertly blending the classical with the contemporary, Matheson creates such a potent brew of nerve-wracking and completely relatable tension that when the monster on the wing of the plane finally makes its appearance, it almost feels anticlimactic.

Matheson was an uncommonly gifted writer. If he had not been so readily identified with his work in the sci-fi, fantasy and horror genres, his talents might have received more attention. Depending on the type of story that he was telling, his prose could be humorous, horrifying, thoughtful and even, as in the case of his time travel novel “Bid Time Return” (later filmed as the 1980 cult favorite “Somewhere in Time“), dreamily romantic. Regardless of the approach, it was always compulsively readable and relatable, whether you were a stone-cold genre fanatic or someone who had absolutely no interest in such things but could appreciate a good story with a catchy plot and interesting characters.

There were a few missteps. The mind boggles to see his name on the credits for the indefensible duds “Jaws 3-D” (1983) and “Loose Cannons” (1990), and it is a shame that despite three shots at it, Hollywood has never figured out a way to properly film “I Am Legend” — Matheson himself felt that the only movie that came close to matching the tone of that book was the otherwise unrelated “Night of the Living Dead” (1968); but for the most part, he was reasonably well-served on the big and small screens, especially when he was involved with the productions. “Duel” and “Nightmare at 20,000 Feet” are his television masterpieces, but an equal case could be made for “Trilogy of Terror,” an anthology that includes an adaptation of Matheson’s short story “Prey.” That tale’s Zuni warrior doll continues to freak out viewers nearly 40 years after its original broadcast.

“The Incredible Shrinking Man” and “Somewhere in Time” have become beloved cult favorites over the years, and even the misfired versions of “I Am Legend” were hits. “The Legend of Hell House” is a suitably creepy take on the haunted house genre, and “What Dreams May Come” is a visual stunner that manages to display real emotion amidst the jaw-dropping special effects. I must also confess a soft spot for “The Box,” in which writer-director Richard Kelly took the premise of Matheson’s famous 1970 short story “Button Button” (a stranger offers you a million bucks if you press a mysterious button even though doing so will cause the death of someone that you do not know) and transformed it into a head-spinner of a tale that took off on its own direction and yet remained true to Matheson and his audacious spirit in unexpected ways. (I know it was reviled when it was released, but I assure you it is worth checking out.)

So now Matheson is gone, and the worlds of literature, film and television are poorer for the loss. If there is any consolation, it is that his works will continue to endure and entertain for decades to come. More importantly, they will continue to inspire new generations of writers and filmmakers to create their own works in the way that Anne Rice has admitted that reading the vampire-themed 1951 short story “Dress of White Silk” put her on the path to try writing her own take on the vampire mythos. And speaking from personal experience, I know that whenever I am driving and the sight of a truck just a little too close to my rear end inevitably sends a chill down my spine, I know exactly who to blame and who to thank.