Of all the lies the movies tell, the cathartic deathbed scene might be the most pernicious. A person lays dying in their bed, while a friend, family member, or unrequited lover kneels or sits next to them. The two have had a complicated relationship, but everything seems simple now. Just before the darkness descends, they look at each other, and an understanding is reached. The sins of the past are forgiven. One can die in peace, and the other can start to truly live.

Where did we get this lie? Is it from the movies, or did our art simply reflect what exists in our hearts back to us? If I close my eyes, I can instantly recall Jason Robards and Tom Cruise speaking without words at the end of “Magnolia“; Winona Ryder crying at Claire Danes’s fevered death rattle in “Little Women“; Billy Crudup telling his father Albert Finney one last fantastic story in “Big Fish“ (at least this film acknowledges the lie); or Debra Winger in “Terms of Endearment“ telling her son that she knows he loves her. In all these scenes, the deathbed brings clarity, turning a complicated relationship simple, and just in time.

That’s not what happens in real life, at least not based on my recent experience. My father and I had a complicated relationship. There were times in my childhood when I didn’t see him for years, and other times when I wished I wouldn’t. I testified against him in a deposition once. He went to jail for a month for violating a court order. As an adult, our dynamic was more like a friendship than a father-son thing. We hung out, talked baseball, and debated politics. I rarely questioned our lack of closeness. I was happy to have a relationship with him that looked more or less normal, even if underneath it was a raging ocean of unexamined emotions.

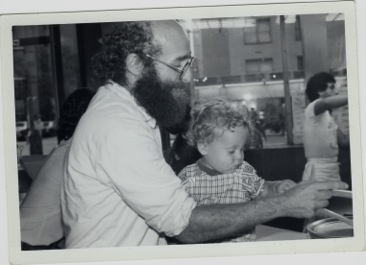

So when he had a stroke nineteen months ago and immediately slipped into a coma, I was hoping for clarity. As a professional film critic and lifelong escapee into cinema, I certainly expected it, so I spent those first several days kneeling by his bedside, trying to talk to him, waiting for the words to come that would fix things. Instead, each day—each moment, really—brought a new rush of emotions. Some days, I wanted to hug him and kiss his bearded cheek. Other days, I pitied him the way I would any person spending his last few days in a hospital. There were days when I wanted to smash his unconscious body with my fists. The day after those days, I felt ashamed.

As he lingered on, the urgency dissipated, but my relationship with him continued. For years, he had set the terms, but now it was up to me. How often would I visit him? Would I speak to him? What would I say? In other words, how did I really feel? As my father lay between being and nothingness, these questions weighed heavily on my mind, a scenario depicted with sharp accuracy in two films released this year. The first is Kogonada’s “Columbus“. The film, released in August, is about Jin (John Cho), a Korean-American man visiting his father, a well-known architect, in the hospital. His father is in a coma and may not live much longer. On the other hand, he could live for months. Jin waits in limbo.

As he waits, he meets a young architectural student (Haley Lu Richardson) and strikes up a tenuous friendship. The two travel around town, admiring buildings, smoking, and talking. Jin reveals his ambivalence about his role caring for his father, especially since the two were never close but is careful not to reveal too much. Kogonada, a video artist with an eye for composition, uses both buildings and actors as props in his carefully-designed frame. Occasionally, it feels as if Cho can’t move lest he disrupt Kogonada’s elegant geometry, but the stillness also speaks to his character. Uncertain of where he stands—with his father, with the girl, and with the world—he simply stands still and hopes that someone else will make the first move. They don’t talk about the future because Jin doesn’t know what it holds. One thing is clear: he would rather be anywhere but in that hospital room, where he is confronted with a relationship he doesn’t understand.

After the initial shock of his situation wore off, I didn’t visit my father very much in the hospital. He was transferred around quite a bit, eventually landing at a rehabilitation center in Harlem. It would have been easy for me to see him there on my way from Connecticut to New York for meeting and screenings. The commuter rail would have dropped me off three blocks away. I ended up only visiting him half a dozen times in a year, convincing myself that I was too busy, or that my presence wouldn’t lift his spirits, anyway. Really, I just didn’t want to be in the room. His friends were always around, telling me, the nurses and doctors, and anyone else who would listen what a great man he was. I was afraid to tell them my truth.

Instead, it came out in my work. One day, I visited him before a screening of “Wilson,” a dark comedy in which Woody Harrelson plays a narcissistic, inappropriate single father trying to befriend his estranged daughter. There were no hospital scenes in “Wilson,” but I found myself wishing there had been. Wilson was an unlikeable, offensive protagonist, I wrote, but that wasn’t a deal-breaker: “The problem is that when he hurts and offends people, the film sides with the offender more often than not.” The film “worships its protagonist as some sort of sage truth-teller whose anti-social tendencies expose our false niceties.” After listening to a queue of his close friends, ex-girlfriends, and distant family members lionize my father to my face, I couldn’t wait to speak my truth about him behind his back, and “Wilson” gave me the opportunity.

My father died on a Tuesday, and I watched “The Meyerowitz Stories” on the following Monday. While “Columbus” captured the mood of having an ambiguous relationship with a dying family member, “The Meyerowitz Stories” tracked the details of my situation with scary accuracy. Like Harold (Dustin Hoffman), the father of three dysfunctional adults who enters the hospital halfway through the film, my father was a lifelong New Yorker, a serial monogamist, and a raging narcissist. He had an aggressively bushy, white beard. He could talk about art, sports, and just about anything else, but he didn’t know how to listen. He could appear interested in what you had to say, but he didn’t care who was saying it.

Like my father, Harold falls into a coma, suffering from a medical emergency that would have been a small matter had he gone to the doctor earlier. For Harold, a simple fall creates a blockage of blood in his brain, and four months later he is in the hospital. My father was having bouts of dizziness and vertigo in early 2016. The vertigo got so bad that he checked himself into the hospital, and we learned he had had a major cerebellar stroke. He was comatose for several months before regaining his faculties, and just as I struggled with my obligations to a father who rarely lived up to his own parental duties, Harold’s son Danny (Adam Sandler) and his siblings Matthew (Ben Stiller) and Jean (Elizabeth Marvel) endure a whirlwind of emotions as their father lays in his hospital bed. I found much of myself in each of these characters, who respond to the difficulties of being raised by a narcissist in disparate, ineffective ways.

Like Danny, I have spent much of my adulthood oscillating between bouts of rage at strangers and extreme sensitivity; he cries over the potential sale of Harold’s apartment (that he never really lived in), while I went to extreme lengths to try to stop my grandmother from selling her idyllic summer home. Both of us were grieving for a childhood we never quite had. Like Matthew, I hoped to satisfy my father with my accomplishments. But Matthew’s money only irritated Harold, and my father never mentioned any of my published work unless it supported a worldview he already held. Finally, like Jean, I found myself always relegated to the background. When my father was in the room, everyone was secondary.

“The Meyerowitz Stories” captures this greater complexity, but it also gets the details, rarely captured on film, right. The shock of seeing your father’s beard trimmed down when I first arrive. The feeling of closeness you have with the doctors and nursing staff, and the awkwardness you feel when you realize they will not reciprocate. The pain of seeing a man known for his loquaciousness reduced by brain injury to monosyllabism. The rollercoaster of good days and bad, and how eventually, they start to spiral down. The way a long stay in the hospital can lead to infections, to a trip to the ICU, to a meeting with the palliative care doctor, a pamphlet about end-of-life care, and instructions on what specific combination of words a dying person need to hear.

Harold gets better in the fictional story, but in real life, my father didn’t. He got pneumonia in both lungs, then developed sepsis, and the antibiotics ceased working. Eventually we decided to move him to hospice. I was actively involved in this decision, and for the first time, it felt like I was willfully participating in his well-being. The simple practice of caring for him made me love him more than ever before. He was on a heavy dose of morphine the day we took him off life support, and after the doctors left the room, I sat with him and stroked his beard, which the doctors had let grow back to its normal length because there was no reason to keep it trimmed.

I started talking, saying all the things they suggest. “I love you. I forgive you. Forgive me. Thank you. Goodbye.” He opened his eyes and rolled them over in my direction.

Did he see me?

Had he ever seen me?

I kept talking, He closed his eyes and did not open them again.

For all of my grappling with my feelings, and for all the lies that cinema tells about the death of a family member, this was as close to a “Magnolia Moment” as I was going to get. And yet frogs did not fall from the sky. He slipped away, and I am left searching the movies for answers, still struggling to make sense of a relationship that I couldn’t find the courage to scrutinize while he was alive. The credits have rolled, but I’m still waiting for the movie to end.